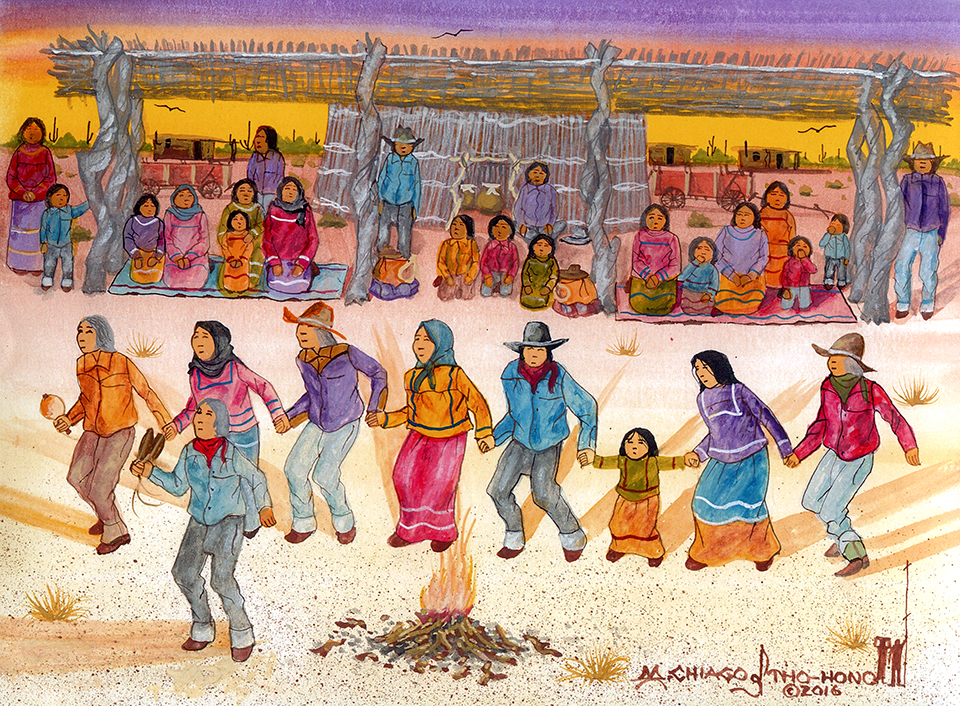

Look closely at Michael Chiago’s watercolors, and you might spot a small boy — he’s hatless and wears a blue shirt. The boy pops up in multiple paintings and typically appears on the edge of the frame or partly obscured in Chiago’s works that portray the sacred rituals and daily routines of Tohono O’odham life: ceremonies, desert harvests, farming.

The boy is a stand-in for Chiago, a self-taught Tohono O’odham artist whose watercolors have brought him international acclaim and were celebrated in the 2022 University of Arizona Press book Michael Chiago: O’odham Lifeways Through Art, a collaboration with ethnologist and ornithologist Amadeo M. Rea.

“Michael never really explained why he painted himself that way,” Rea says. “He just said, ‘I’m watching. And I’m learning.’ If you go through each one, you see he’s the inquisitive one and saying, ‘Hey, I’m learning my culture.’ ”

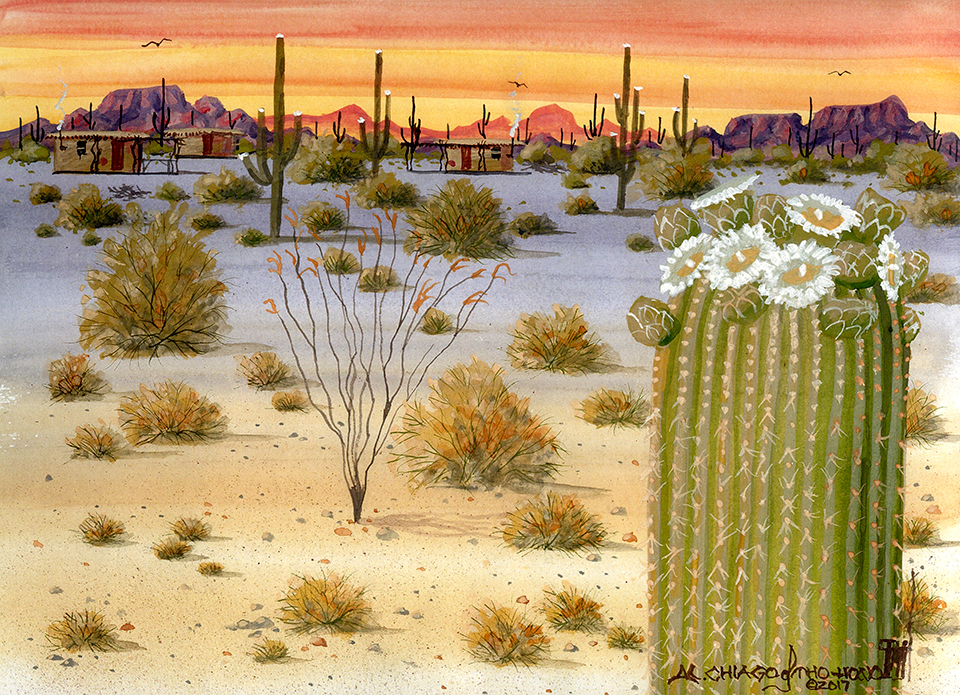

The boy’s stealthy cameos are a reminder that Chiago’s paintings merit close examination, both for their artistic quality and for his meticulous portrayal of the traditional O’odham world. Chiago’s watercolors can initially appear deceptively simple, and many of his works share a common visual rhythm: people in the foreground, buildings or desert plants in the middle ground, mountains in the distance, almost always with birds soaring in the sky and rendered as simple wavy lines — not unlike the way a child might paint them.

The faces are uncomplicated, almost featureless, with quick dashes and dots for the nose, eyes and mouth. But look closer, and the people in the paintings always stand out as distinct individuals, seemingly with stories of their own, even in such watercolors as 2015’s Village Feast Day Celebration, in which Chiago painted a crowd of more than 50. A cock of an eyebrow or turn of the head is enough to suggest everything from distraction to devotion. And the details are endless: hatbands, hair braids, kerchiefs, spurs on boots, cuffed jeans, the sense of movement created by the billow of a woman’s dress or the bend of a guitarist’s knee.

Rea writes, “This is not an art book,” and he considers the collaboration more of an examination of the ways Chiago sees and portrays his culture. But he deeply respects Chiago’s artistic commitment. “Michael is … he’s a compulsive artist,” he says, pausing for the right words. “It seems like every time I phone him, he’s in the middle of buying art supplies, or else he’s at home, painting. But even when I’ve talked to Mike about his influences, he’s sort of [like], ‘Well, I just paint.’ And he makes a point of saying, ‘I don’t follow anyone else’s school.’

“So, I try to emphasize that in the book. He has forged his own way of depicting things — and it’s not part of any other Native American art school. It’s his own thing. And he always pursues it.”

On a gusty winter morning, I drive down from Tucson to meet Chiago at Mission San Xavier del Bac. A few miles from the mission, black smoke rises from a wind-driven brush fire in an arroyo, while dust swirls in the plaza where we’ve agreed to meet.

Chiago wears a baseball cap, jeans and a windbreaker. His close-cropped mustache stretches to deep grooves that extend down from his nose to join the lines at the corners of his mouth. Chiago looks compact and strong at 77, and there’s nothing about his unassuming manner that would distinguish him as an acclaimed artist and chronicler of his people’s traditions.

We stroll to the church and settle into a pew about halfway back from the retablo mayor as devotional music fills the baroque space. For a couple of minutes, we sit in silence, taking in the church’s grandeur, and I look over and watch Chiago’s eyes track a course across the elaborate interior, assessing the ongoing renovations. It’s a familiar place for Chiago, and with a little lift of his head, he directs my attention to one spot. “They moved that statue over there,” he says. “I think they’re almost done in here. Because it’s all really clear.”

Chiago was born in the village of Kohatk, about 65 miles northwest of San Xavier del Bac, but never visited the mission until he was an adult. “Yeah, I was really amazed when I walked in it,” he says. “The decorations that they have in here. It used to be gold — all of it looked like the real kind of gold, but it was just painted. Now, it’s all soft colors. This is nice now. I get to see it all finished. Every time I come over here,

I sit for a while, look at the statues.”

Chiago tells me his paintings are part of the collection at the mission’s museum, and I ask how it feels to have his works displayed at such a significant landmark. “Oh, yeah, yeah, I feel really, really honored,” he says. “They bought them when, I don’t know, someone donated millions of dollars to the church. They announced that they wanted to buy some paintings — my paintings. They told me not to lower the price down and bill what I want to bill. They bought everything. Must be, like, eight or 10. They’re not big paintings, but they’re in frames.”

Chiago talks a lot about the logistics of being an artist: dealing with gallery owners and getting ready for art markets, making deliveries, and the details — down to the drilling — of installations he completed years ago. I sense that he doesn’t regard these as unpleasant tasks that are somehow beneath him or intrude on his creativity. It’s all just part of the job.

After studying the mission’s facade, Chiago and I find a ramada outside the gift shop that’s sheltered from the desert wind. I tell him I first became aware of his work maybe 15 years ago, when I saw his 50-foot outdoor mural of O’odham life on a wall along Vananda Avenue in Ajo.

“They had people in Ajo help me,” he says. “I sketched it, and they filled in the colors. Used house paint. And after they were done, I corrected it a little bit. Lightened the faces, and we put on a coating so it wouldn’t fade out. A lot of people helped. At the end of the wall, they have their handprints. Took us, like, four months to finish the wall.”

Chiago grew up at a time when the O’odham people hauled water in 50-gallon drums from a village windmill. There was no electricity, and people traveled by horse-drawn wagon. The book describes how Chiago’s parents had to undertake a wagon journey of several days to reach the midwife in Kohatk who delivered him.

His parents worked in the cotton fields, and the family moved frequently, delaying Chiago’s education for a couple of years, before he attended the government-run Santa Rosa Boarding School in Sells, the capital of the Tohono O’odham Nation. Chiago’s artistic talent was obvious, even from a young age, and a second-grade teacher gave him the art supplies he needed. He drew the desert landscapes he knew — the big skies and mountains and saguaros — and usually won the weekly art contest in his class.

“They gave everybody the chance to draw something,” he recalls. “The teachers, they were always picking my art as the best. We just used crayons — we didn’t use watercolors. They were always suggesting I go to art school. I didn’t know that there were such schools as art schools.”

Chiago later received more encouragement after transferring to St. John’s Indian School in Komatke, southwest of Phoenix. He loved basketball — “We played really fast” — and in high school learned how to cut hair to pick up extra money. It was at St. John’s that Rea and Chiago met. Back then, Rea was a Franciscan friar who started teaching biology at the school during Chiago’s senior year. Chiago ended up cutting Rea’s hair and almost 60 years later remembers that Rea preferred a short flat-top.

Chiago’s world began to expand. He joined a troupe that performed Plains Indian-style dances. The school didn’t offer much art instruction but did teach leatherwork and other crafts, so Chiago ended up making his own chaps and headdress for the dances.

The troupe marched in parades and traveled as far as Seattle, then to New York to dance at the 1964 World’s Fair. Considering that he grew up immersed in traditional Tohono O’odham lifeways and listening to the stories of his mother and grandmother, I’m curious to hear about Chiago’s culture shock upon arriving in New York. But he doesn’t have much to say: “Their clothing was all black. Nobody was ever wearing colorful clothing. Maybe it was because of the weather. I don’t know.”

Instead, he focuses on the process of the trip. He says he was waiting for his barber’s license and couldn’t leave Arizona, then rode a Greyhound bus, with an overnight stay in Denver, before catching up to the other dancers in Des Moines, Iowa, and spending a night in Chicago. His regalia arrived late in New York, so he never danced at the World’s Fair. But he did perform in Central Park and at a USO center, where the group passed the hat to bring in travel money. Then, the troupe continued to Washington, D.C., while Chiago and a friend from Casa Grande boarded a Greyhound and left New York for the three-day return to Phoenix.

He does remember the landscape. “That was my first time seeing the eastern part of the country,” he says. “Everything is so different — not like anything in the West. There were no mountains. Nothing, just flat — everything was just flat. Hills, maybe, but not as big as the big mountains out here. That’s one thing I like about Arizona. ’Cause of the mountains. I lived around the mountains growing up, climbing the mountains near Casa Grande, sometimes, when I was younger, with my brother. He brought a sketchpad and sketched the farms and everything. He didn’t take up art, my older brother. He just did it for fun.”

During the Vietnam War, Chiago left his job at a Phoenix barbershop and enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps. He was the third Marine in his family and wanted to fight. Instead, a master sergeant noticed his barber training and, despite Chiago’s objections, assigned him to cut hair for the platoon. Chiago operated out of an improvised shop marked by a spent mortar shell he painted with red and white stripes.

After returning to Arizona, Chiago used his GI Bill benefits to study commercial art and worked on layouts for a magazine before committing to a painting career a few years later. His works featured Plains Indian imagery and kachinas, and at first, Chiago didn’t think to depict his own culture. But he found his creative direction when he turned his focus to O’odham subjects.

It wasn’t easy. Chiago churned out paintings at a rapid clip, sometimes sacrificing his high standards to try to make a living at $15 per watercolor. He has no idea how many watercolors he has painted over his career.

The acclaim came slowly. Chiago’s appearances in Arizona Highways brought his art to a wider audience, and his 1999 cover depicting an O’odham folktale about saguaros became one of the magazine’s best-selling issues. He traveled to London as artist-in-residence at the Museum of Man, and in 2012, he was one of 12 Indigenous artists featured in a Paris exhibition.

I haven’t managed to prompt Chiago to elaborate on his New York experience, and as we have a lunch of fry bread tacos at the snack bar, I’m no more successful in my attempts to get his impressions of Paris: He remembers rain and pickpockets and the turnstiles in the Metro. A museum he’d hoped to visit was closed, but he’s not sure of its name.

But Chiago comes alive when he’s talking about his own art — not about some grand vision, but about method. He goes into long explanations about his technique for mixing paints (he has long used Grumbacher watercolors) to achieve the luminous opacity of his works and the subtle quality of the hues. He says he always goes back through the entire painting to make sure there are no spots that need to be smoothed out. “If you leave those, it just makes it look like you didn’t care about your art,” he says. “That you didn’t pay attention.”

Chiago uses his old brushes for detail work because they’re skinnier and let him achieve the effects he wants. “I try to be real accurate,” he says. “The eyes have to be right. The mouth has to be right. The glow of the buttons. The wrinkles in the clothing.”

We’ve been talking for nearly three hours, which surprises Chiago because he thinks it’s only been about an hour. Before saying goodbye, I tell him so many artists seem to have huge egos but that he’s refreshingly humble. I ask whether, more than anything else, he simply thinks of himself as a working artist.

He smiles and says, “Yeah, I really like to paint. Yeah. I do it every day. I want the paintings to be perfect.”