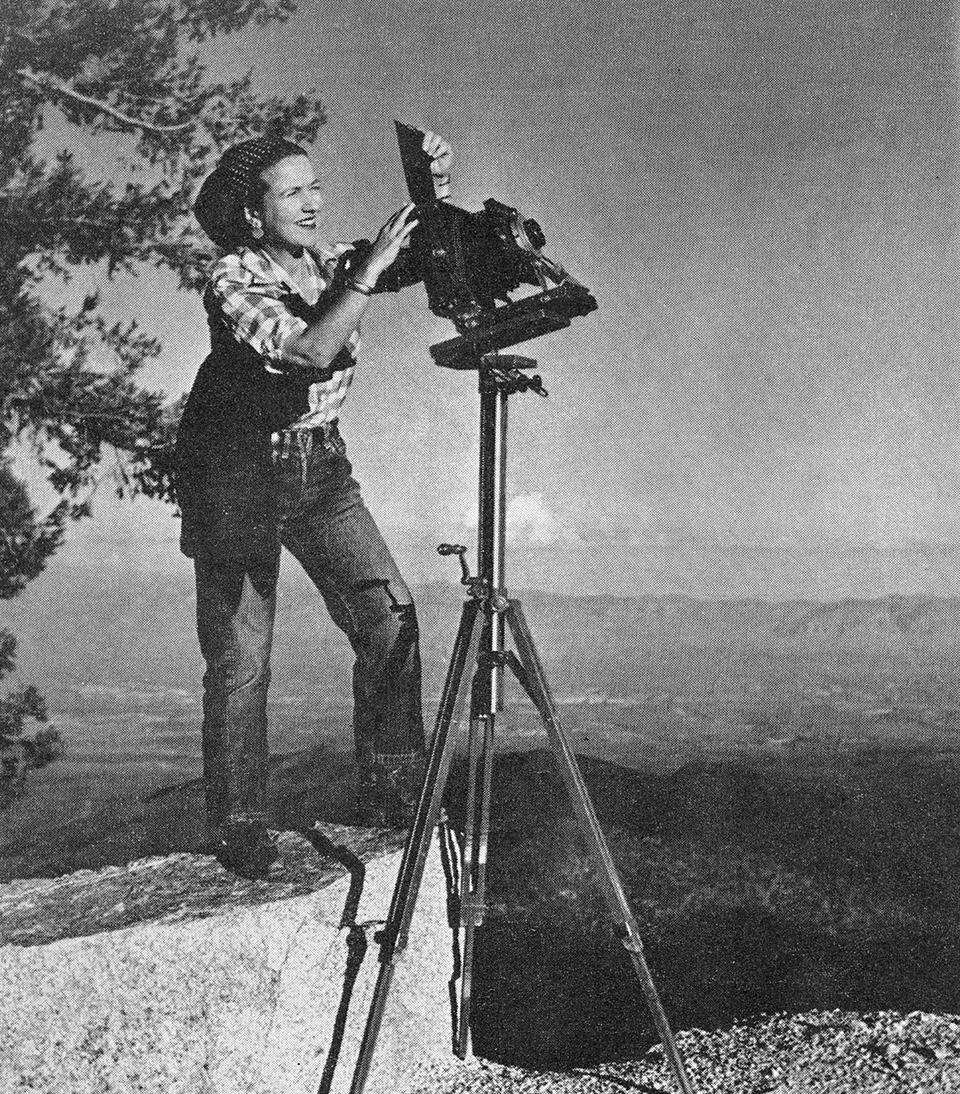

Esther Henderson

Photographer

1911–2008

Esther Henderson arrived in Arizona at the end of a winding journey that began in her native Illinois and included time in New York City as a cabaret dancer. Having promised her father that she’d change careers before turning 25, she learned commercial photography and portraiture. But when she got to Tucson in 1935, she recalled decades later, “It didn’t take long to find that I had already made the first mistake: choosing a business that would keep me in a darkroom after I had come to a land of sunlight.”

Thus, she augmented her studio work with landscape photography, and her work in that discipline caught the eye of Arizona Highways Editor Raymond Carlson, who stopped by her Tucson studio in search of scenic photos. At the time, Carlson was beginning the magazine’s transition to a publication focused on travel and tourism. Ultimately, Henderson’s photos became the first Carlson ever purchased for the magazine.

Soon after that, Henderson married fellow photographer Chuck Abbott, and while they both contributed extensively to the magazine for decades, Henderson had the most ambition and the keenest photographic eye. With their two sons in tow, the couple ventured all over the American West, first via tent camping and later in a 19-foot Aljoa trailer.

Henderson’s photos of the Grand Canyon, Monument Valley and other well-known Arizona destinations helped make the magazine renowned around the world. She often included a human subject in her images — one of her most famous, from our March 1954 cover, shows a horse and its cowboy, a wrangler named Jay Gaza, peering into the Canyon from the South Rim. That practice was in keeping with what Henderson called “a never-ending search” to interpret the Southwest’s majesty in human terms.

“For all its challenges, my Southwest has its rewards,” she added in a 1968 retrospective. “There is no land so wide, so empty of people, so full of promise.”

— Noah Austin

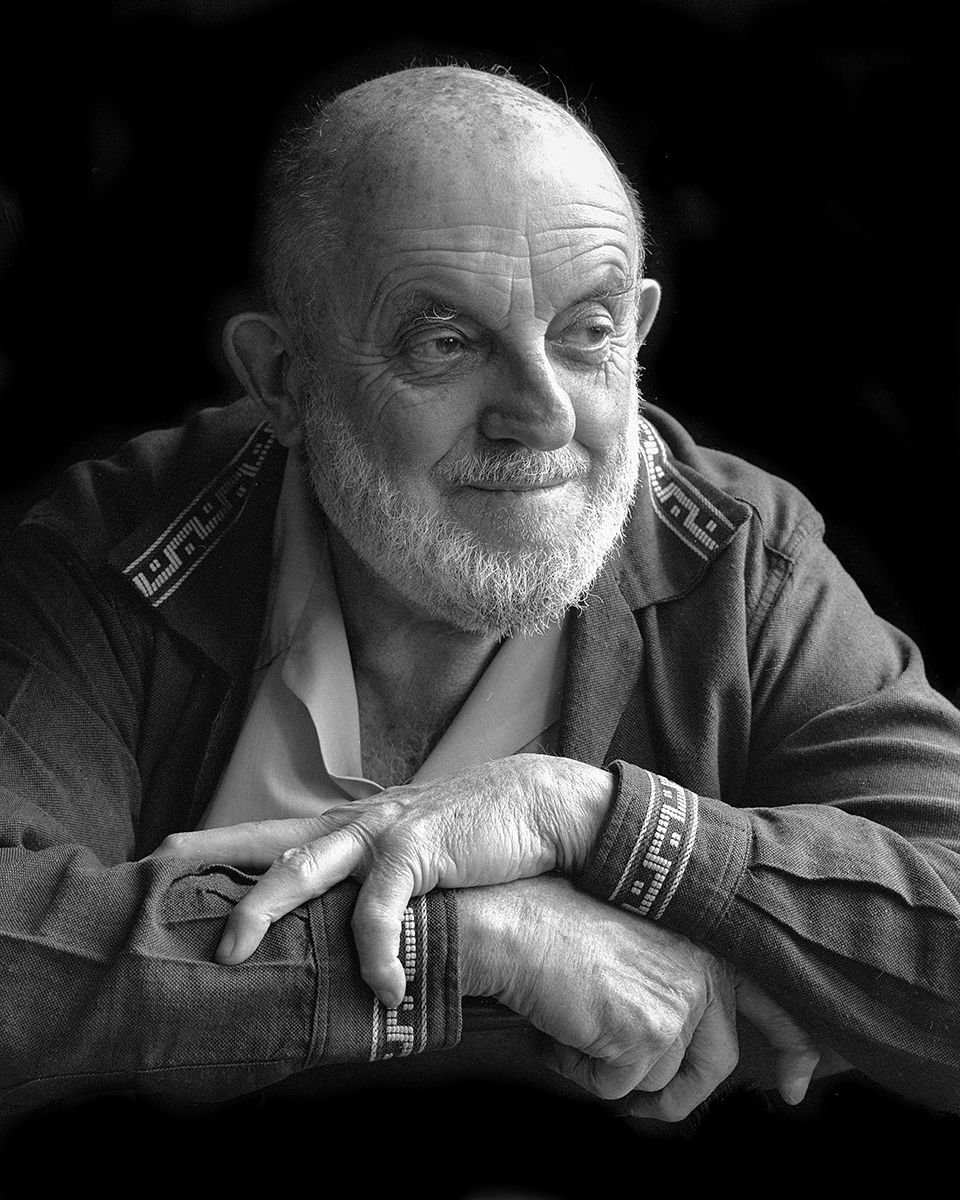

Ansel Adams

Photographer

1902–1984

“I have a far-flung reputation now which I am anxious to cash in on in a thoroughly dignified (and profitable) manner,” photographer Ansel Adams wrote in a letter to Arizona Highways Editor Raymond Carlson in the 1950s. His first photograph, a color study of Monument Valley, was published in our pages in 1946, when he was already well established as a landscape photographer.

As a child growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area, Adams was drawn to nature and took frequent long walks along Lobos Creek and down to Baker Beach, according to biographer William Turnage. And while Adams was a talented pianist who intended to turn music into a career, the time he spent exploring the Yosemite area with the Kodak No. 1 Brownie box camera his parents gifted him transformed his life’s passion. His first published photographs appeared in the Sierra Club’s 1922 bulletin. And according to Turnage, “By 1934, Adams had been elected to the club’s board of directors and was well established as both the artist of the Sierra Nevada and the defender of Yosemite.”

Adams perfected his craft and became acquainted with Edward Weston, Mary Austin, Paul Strand and Alfred Stieglitz; the latter helped advance Adams’ career by offering him a solo show at his gallery, An American Place, in 1936.

As his career progressed, Adams became well known, too, for his work in the darkroom. In a 2014 article in Arizona Highways, Alan Ross, Adams’ assistant and friend, highlighted his artistic vision: “I’m not sure how much I learned that was unique to Ansel, but being in the darkroom and watching him work was amazing. I never saw him make a straight print — just expose the paper to record the negative. The process was always an artistic expression of dodging and burning. He used a metronome to count seconds and didn’t even own a timer. He counted the exposure for everything he did in the darkroom. Seeing how smoothly everything moved was like watching a ballet. Ansel was totally in control of how much light was given to every part of the paper.”

Adams’ work in Arizona Highways was extensive, a product of his long friendship with Carlson. And, as noted elsewhere in this issue (see page 23), he even offered a collection of 150 images to the magazine for $1,500. Today, Adams’ collection is housed at the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

— Kelly Vaughn

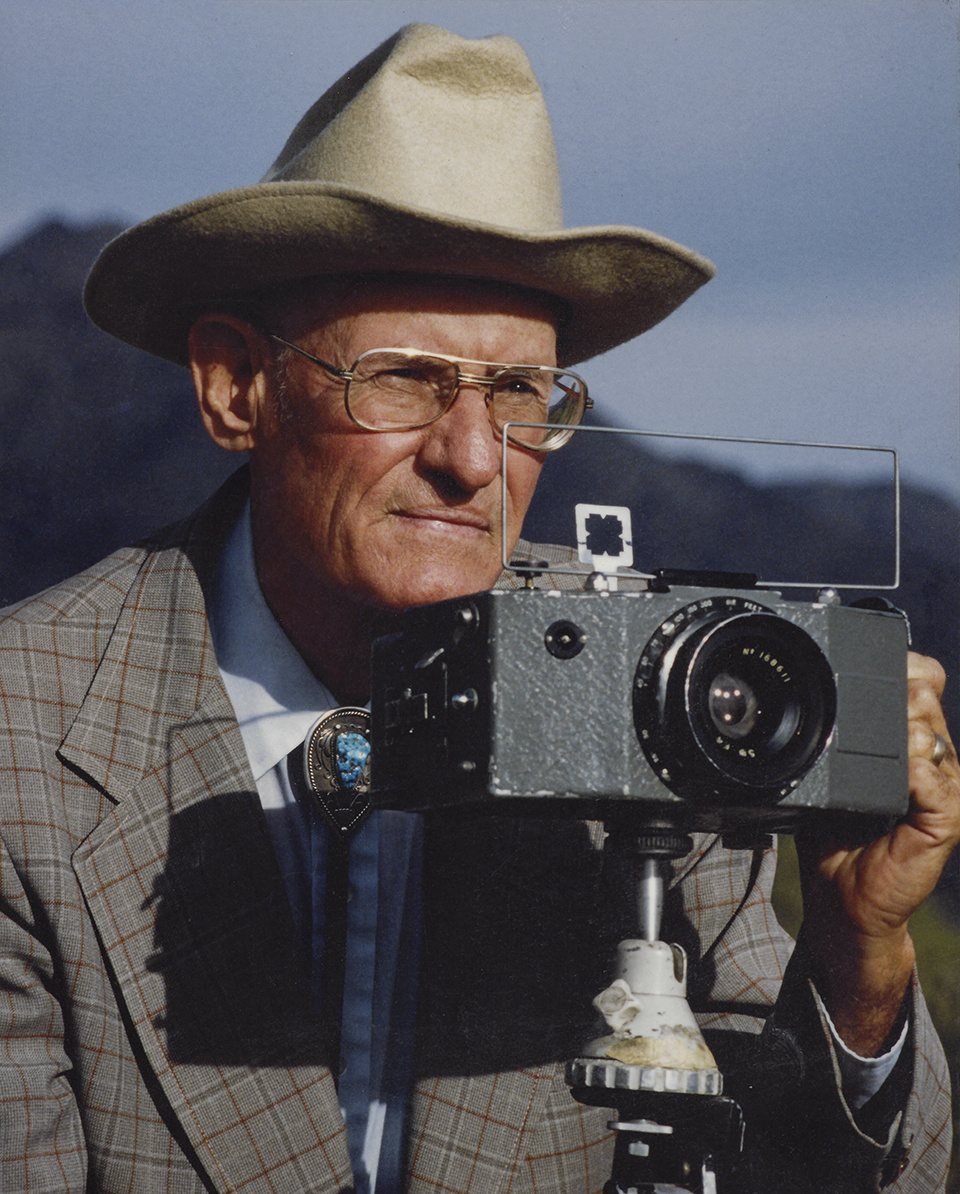

Norman G. Wallace

Photographer

1885–1983

By William Wyckoff

As soon as Norman G. Wallace arrived in Arizona Territory from his native Ohio in 1906, he fell in love with the landscape of what soon would become the 48th state. Fortunately for Arizona Highways, he channeled that affection into photographing the natural beauty, small towns, historic sites and just about everything else under the Arizona sun. And he blended his passion for photography with his career as a surveyor and civil engineer, a profession that took him to every corner of the Grand Canyon State with his camera by his side.

Wallace’s early surveying work sent him in many directions. From 1906 to 1931, he was employed as a draftsman and transitman for the Southern Pacific Railroad, surveying rail lines across the Southwest and northern Mexico. But after he was laid off by the railroad during the Great Depression, he took a new position with the Arizona Highway Department, a predecessor of today’s Arizona Department of Transportation, in 1932. He worked there as a transitman, surveyor and civil engineer; then, from 1943 to 1955, he served as Arizona’s chief location engineer. Throughout his 23 years with the Highway Department, he fundamentally shaped the state’s developing road network.

Soon after his hiring, he paved the way for modernizing Route 66. In later years, he lived in isolated tent camps around the state as he and his survey crews located and improved dozens of Arizona’s signature highways. He would spend weeks away from his wife, Henrietta (whom he married in 1934), roughing it in the state’s rugged backcountry. Wallace loved the work, spending days in out-of-the-way places with a motley crew of chain men, rod men, levelers, brush cutters and a cook. Recalling those years, Henrietta estimated her husband had camped in more than three dozen spots around the state as he surveyed Arizona’s modern highway network into existence.

Many of Wallace’s major surveying accomplishments with the Highway Department remain with us today. In addition to the improvements he supervised along Route 66, he located and modernized stretches of U.S. routes 60, 70 and 80 in the central and southern portions of the state. Arizona’s rugged canyons and mountains were constant challenges but rarely discouraged him. He helped modernize present-day State Route 64, along the Grand Canyon’s South Rim; the Apache Trail (State Route 88), east of Phoenix; and the Coronado Trail (present-day U.S. Route 191), through the White Mountains. And he was especially proud of his work along the Black Canyon Highway (later Interstate 17), which eventually forged a high-speed link between Phoenix and Flagstaff.

Through all these expeditions, Wallace’s camera was by his side, and he made thousands of pictures that recorded both his highway projects and the wider Arizona landscape he deeply cherished. When he wasn’t working, he would take “picture trips” on his days off or enjoy longer excursions with a camping buddy or two to explore some corner of the state he wanted to see and photograph. And within a year of Wallace’s hiring, his superiors at the Highway Department began to use his photographs in the department’s signature magazine, Arizona Highways.

Some of Wallace’s pictures in the magazine documented state-funded work on highways, but increasingly, his images of desert vistas, cactuses, sweeping cloudscapes, mining towns and historic sites promoted a broader vision of Arizona’s character and beauty. Indeed, Wallace’s published work in the magazine between 1932 and 1955 — photographs, as well as dozens of articles he authored — helped transform Arizona Highways from a technical publication focused on road and bridge building into the state’s flagship promotional periodical, one that reached millions of appreciative readers in the United States and beyond.

Wallace’s love of photography had begun early in life. His father, an accountant in Cincinnati, dabbled in picture taking, and young Wallace picked up the hobby. When he arrived in Arizona, he had a simple Kodak box camera, but in later years, he acquired more sophisticated equipment. At various points in his career, he owned a large-format 8x10 bellows camera, a 5x7 Graflex, a medium-format Zeiss Ikon Ikonta and a Ranca miniature camera, which he used for making color exposures beginning in the late 1930s.

Wallace readily embraced color photography, a skill that served him well in polychromatic Arizona and in his work for Arizona Highways. He was especially proud of producing a photograph of lower Oak Creek Canyon that would be the first color photograph to appear on the cover (July 1938). Henrietta even endured his photographic passions on their honeymoon, when he spent hours photographing the Grand Canyon — a trip that produced a future cover photo and story for the magazine (January 1935). As she lamented, “He was married to his cameras before he was married to me,” and much of that romance continued in later years. But she grew to accept Wallace’s desire for careful image making and patiently endured his lengthy roadside stops to capture just the right scene.

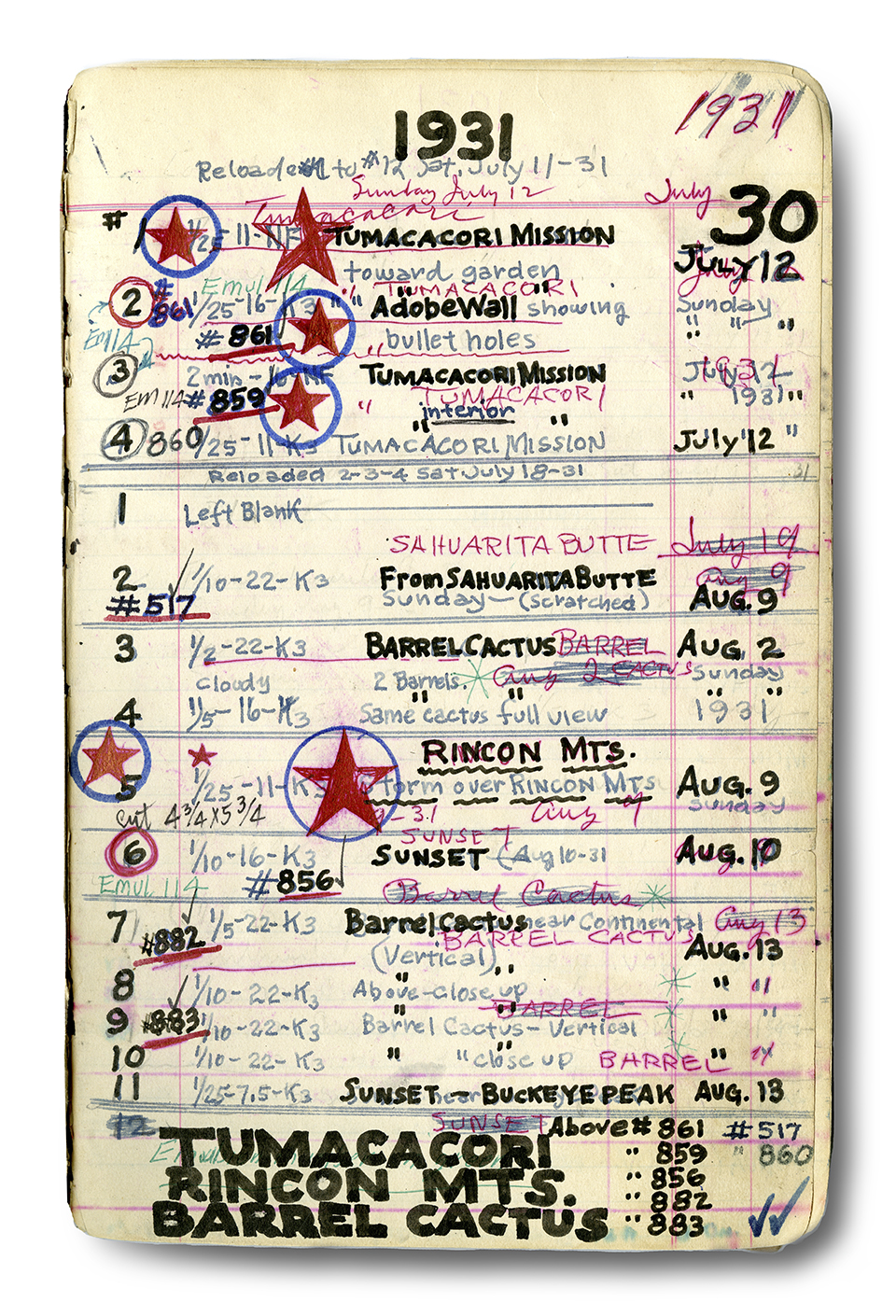

Wallace’s voluminous logbooks meticulously documented his photographic adventures. In more than 1,400 pages of detailed notes spanning many decades of picture taking, he noted the precise location and circumstances of thousands of exposures as he took them. Both his work-related images (“state pictures”) and his personal photographs (“art pictures”) were noted in the logbooks, and many were later annotated with bold stars (for a good shot) or complaints about “bad luck” or “blurred prints.” His daily dose of logbook entries would often include humorous commentary, such as the time he was camped north of Cameron on a chilly night beneath the stars at the “Hotel de Wallace.”

Wallace embraced diverse subject matter in his photographs and stories. Arizona’s natural landscape was vastly different from that of his native Midwest, and he learned the Latin names for desert cactuses and when and where yuccas and ocotillos would be in bloom. Many of his short, illustrated articles in the magazine focused on nature and carried headlines such as Storm in the Arizona Desert (October 1935), It’s Springtime in the Desert (May 1936) and Snow! Strange Sights Greet Arizonans (February 1937). In his personal collection of images, he had files labeled “Cactus Plants,” “Cloud Effects,” “Superstition Mountains” and “Wild Animals,” among other subjects.

He shared a similar passion for history, and ancient Puebloan settlements, Hispanic churches and Territorial forts always caught his eye. Predictably, his fascination with the past was captured through the lens of landscapes. Wallace often visited the windswept ruins of Wupatki National Monument, established in 1924, and loved camping there, sketching and photographing the surviving brick walls and towers. He also was drawn to Mission San Xavier del Bac, not far from his home base in Tucson; he visited dozens of times, and his shot of the church was featured on an early cover of Arizona Highways (December 1932). He also published an article on the Native history and scenery of Canyon de Chelly (Canyons of Death, November 1936).

One of Wallace’s favorite historical adventures, though, was following in the footsteps of Lieutenant Edward Beale’s federally funded wagon-road survey across present-day Northern Arizona in 1857. Memorably, Beale’s explorations featured two dozen African camels that carried the expedition’s equipment and provisions. Wallace delighted in rereading Beale’s journals, following the precise route of his journey and photographing the scenes along the way. In Arizona Highways, he published his detailed narrative of the trip, The Trail of the Camels, in October 1934.

The highways that Wallace modernized became leading characters in his photography and writing. He had an aesthetic attraction to a beautiful road — Henrietta recalled that he loved to take “a picture of a road that was always curving” and that she knew when and where he would stop along a highway. As his archive grew, he organized hundreds of his images by highway number, making it easy to find them and use them in his work. For Wallace, a highway was a story that unfolded across the Arizona landscape, taking travelers up and over spectacular grades, across rugged terrain, and through mining towns and desert scenery.

Some of Wallace’s best photographs and articles that appeared in Arizona Highways literally featured Arizona’s highways, and they were powerful promotional pieces that celebrated the state’s good roads and all they traversed. In one of his last contributions to the magazine, in May 1955, he penned a lengthy piece on one of his most beloved roads: Arizona 66: The Scenic Wonderland Highway. The essay follows Route 66 from east to west as it crosses Navajoland (“most of the terrain will be of the wide-open spaces type”), summits the pine-studded Coconino Plateau near Flagstaff (the “finest part” of the state) and descends toward the Colorado River (the “vastness of the desert regions of Western Arizona”). It was a captivating journey Wallace had taken countless times as he worked to modernize the Mother Road.

Wallace and Henrietta moved from Tucson to Phoenix in 1950, and Wallace retired from the Highway Department in 1955, at age 70. The couple witnessed the extraordinary expansion of the Valley of the Sun that saw Phoenix’s population grow from 100,000 in 1950 to 800,000 in 1980. Wallace spent his retirement organizing his photographs before donating a large collection to the state in 1968. His work was later honored in a display at the state Capitol in 1976.

He kept making photos, too — taking short trips around the state, revisiting familiar spots and favoring Ektachrome color slide film. There were pictures of Arizona scenery, special bridges and overpasses, and more intimate local portraits of a sunset at the house or a neighbor’s flower garden. Wallace remained engaged with the visual scene in these later images, but that world was shrinking — a far cry from his earlier, far-flung adventures.

Wallace died in Phoenix in 1983, at age 98, and Henrietta gave many of his remaining photographs to the Arizona Historical Society in 1984. The collection grew larger thanks to donations from Arizona Highways in 1999, and today, Wallace’s legacy is preserved in the Norman G. Wallace Photograph Collection at the AHS in Tucson. Occupying 55 boxes of material, the collection celebrates Wallace’s prolific photographic talents, his long career creating Arizona’s highways and the visual treasures of a state he dearly loved.

• William Wyckoff is the author of Riding Shotgun With Norman Wallace: Rephotographing the Arizona Landscape (University of New Mexico Press, 2020).

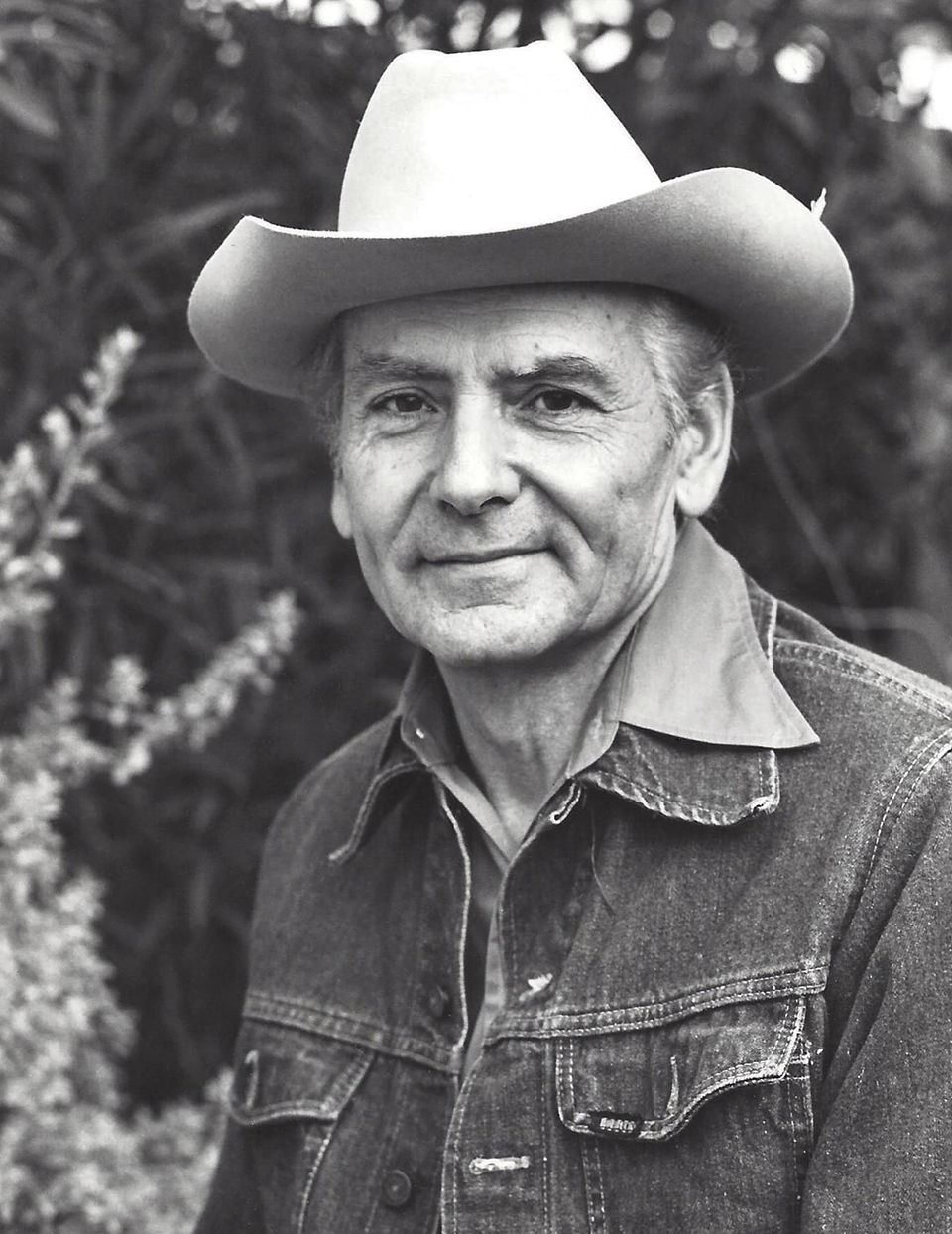

Josef Muench

Photographer

1904–1998

Josef Muench’s prolific relationship with Arizona Highways is one the Bavarian immigrant likely couldn’t have imagined when he quit the Ford assembly line in Detroit and headed west in a Model T in the 1930s. And it’s a relationship that endures today, as we continue to publish Muench’s photos nearly three decades after his death.

After Muench settled in California, his growing talent for landscape photography funded trips around the Southwest, including Arizona, which he first visited in 1936. He met Arizona Highways Editor Raymond Carlson two years later and soon sent a package of transparencies to the magazine. From that package came the cover photo for the July 1939 issue — a spectacular shot of Navajo Falls in Havasu Canyon — and interior shots of Rainbow Bridge and Monument Valley in the same issue. After that, Muench’s work became a constant presence on the magazine’s pages — as did Muench himself, who often appeared in his own photos while wearing his trademark red shirt.

In introducing a 1969 look at Muench’s work, Carlson noted that “Joe’s name has appeared in our credit roster more often than that of any of our other contributing photographers.” And while Muench ventured all over the state, the Navajo Nation particularly fascinated him, and his photos played a key role in luring Hollywood to Monument Valley and making that site an enduring symbol of the West.

For years, when asked for his favorite place in Arizona, Muench offered a cagey answer: “Wherever I am at the moment.” Later in his career, though, he admitted that only one location had impressed him enough that he’d meticulously cataloged each of his visits. “Just recently, I counted my 160th appearance in beautiful and exciting Monument Valley,” he wrote. It was a fruitful fascination — for him and for us.

— Noah Austin

Clara Lee Tanner

Writer

1905–1997

“I think that the Southwest itself has something you can’t put your fingers on — it just is,” Clara Lee Tanner said in the 1980s, near the end of a long career spent studying and writing about Indigenous arts, crafts and ways of life. “And it is beautiful, and it is vast,” she continued. “I think it was rather natural that my interests in the Southwest would end up in Native art.”

Born Clara Lee Fraps in North Carolina, she spent most of her life in Tucson, where she earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in archaeology from the University of Arizona. She subsequently taught there for 50 years and authored several university-published books on Southwestern tribal art. Early in that tenure, she also began contributing to Arizona Highways at a time when the magazine was still primarily an engineering publication.

Her first byline, before her marriage to John Tanner, came in March 1931, when she wrote about centuries-old customs still retained by Arizona’s tribes — a subject in line with her long-standing interest in documenting cultural continuity. Her subsequent work included features on prehistoric agriculture and Native turquoise jewelry. And in August 1945, her Shepherds of the Desert, on Navajo shepherding and weaving practices, accompanied Joseph Miller’s famous cover photo of a young Navajo girl with her lamb.

Few, if any, writers can claim as long an association with Arizona Highways as Tanner; hers continued into the late 1980s, when she was listed on the masthead as a senior contributing editor. In 1993, she received a lifetime achievement award from the National Museum of Women in the Arts. In nominating her for that award, fellow longtime contributor Barry Goldwater wrote, “I don’t think I have ever known a man or woman who has done more for the culture, history and understanding of the American Indian in the Southwest than Ms. Tanner.”

— Noah Austin

Allen C. Reed

Photographer

1916–2009

Prolific. That was Allen C. Reed’s work for Arizona Highways. And, really, that’s an understatement. For decades, beginning in July 1949, Reed photographed and authored more than 50 articles for the magazine, many of which were about the Navajo and other Indigenous people of the state. In August 1952, for example, he wrote and photographed a feature titled Navajo Tribal Fair.

“To Kii yazhi it was a very special sun that peeped over the plateau of his native Navajoland that cool mid-September morning,” Reed wrote. “With his robes pulled tightly about his shoulders, he sat leaning against a wheel of his father’s wagon, anxiously watching the eastern sky. He had waited silently in the darkness long before the first rosy glow of dawn tinted the wispy clouds.”

Reed was a natural storyteller whose words were as painterly as many of his images. Born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, in 1916, he attended the Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles; there, he met his wife, Shirley. During World War II, Lockheed hired him to illustrate military aircraft parts and repair manuals. After the war, the Reeds relocated to Phoenix, where they opened an advertising agency — a pursuit Reed balanced with his extensive travels across the Southwest, making photographs and writing about his experiences.

And even though many of Reed’s stories took place in the Four Corners region of Arizona, he didn’t shy away from more central locations. In March 1951, Arizona Highways published a 10-page feature wherein Reed did double duty.

“She’s quite a character, the Verde [River], with moods by the mileful,” he wrote. “She’ll ponder for a few hundred yards in deep meditation, burst forth in a gay spurt of foam and spray, splashing through the shallows, swirling down the narrows, splitting at a sandbar, racing herself to the other end and running her fingers through the tall grass and willows of a half-submerged island only to pause again, catch her breath and lag along in another deep, quiet pond.”

After Reed retired, he relocated to Greenehaven, where he continued to make photographs while running a real estate sales office. Although he died in 2009, his legacy lives on in the pages of Arizona Highways.

— Kelly Vaughn

Ted DeGrazia

Artist

1909–1982

Then-Arizona Highways Editor Joe Stacey once wrote that had Mary Helen Carlson — the wife of Stacey’s predecessor, Raymond Carlson — not discovered Ted DeGrazia in the 1940s, the artist might have made his living as “Arizona’s most illustrious bar mural painter.” And while Carlson introduced DeGrazia to an international audience, the prolific Italian from Morenci more than returned the favor, helping to establish Arizona Highways as a publisher of fine art, not just great photography.

DeGrazia’s early work brimmed with social and political realism, but over the decades, the magazine’s readers watched him move away from that style in favor of commercial appeal. That evolution still inspires debate among art critics, some of whom also note DeGrazia’s penchant for self-promotion. But there’s no debating his skill with a palette knife or the joy he took in portraying the people and landscapes of the American Southwest.

His kindness, too, touched the magazine’s readers multiple times — such as in September 1971, when an original DeGrazia work appeared in the magazine. “We feel that Ted’s Little Cocopah Indian Girl is the finest pastel he has ever done,” the accompanying text read, adding that for $5, readers could buy a print of the painting to support the Yuma area’s imperiled Cocopah Tribe. “So long as there is one of God’s creatures to help,” the writer predicted, “Ted will talk it over with his angels and from his Santo Bandido heart will come another inspired deed.”

Less than a decade later, Raymond Carlson was retired and facing money troubles. DeGrazia established a trust in Carlson’s name and donated two more original works, and Arizona Highways sold prints of them for $7 apiece. The project raised $60,000, the equivalent of more than $250,000 today, for the Raymond Carlson Trust, which saw DeGrazia’s old friend through the final few years of his life. Not bad for a reformed “bar mural painter.”

— Noah Austin

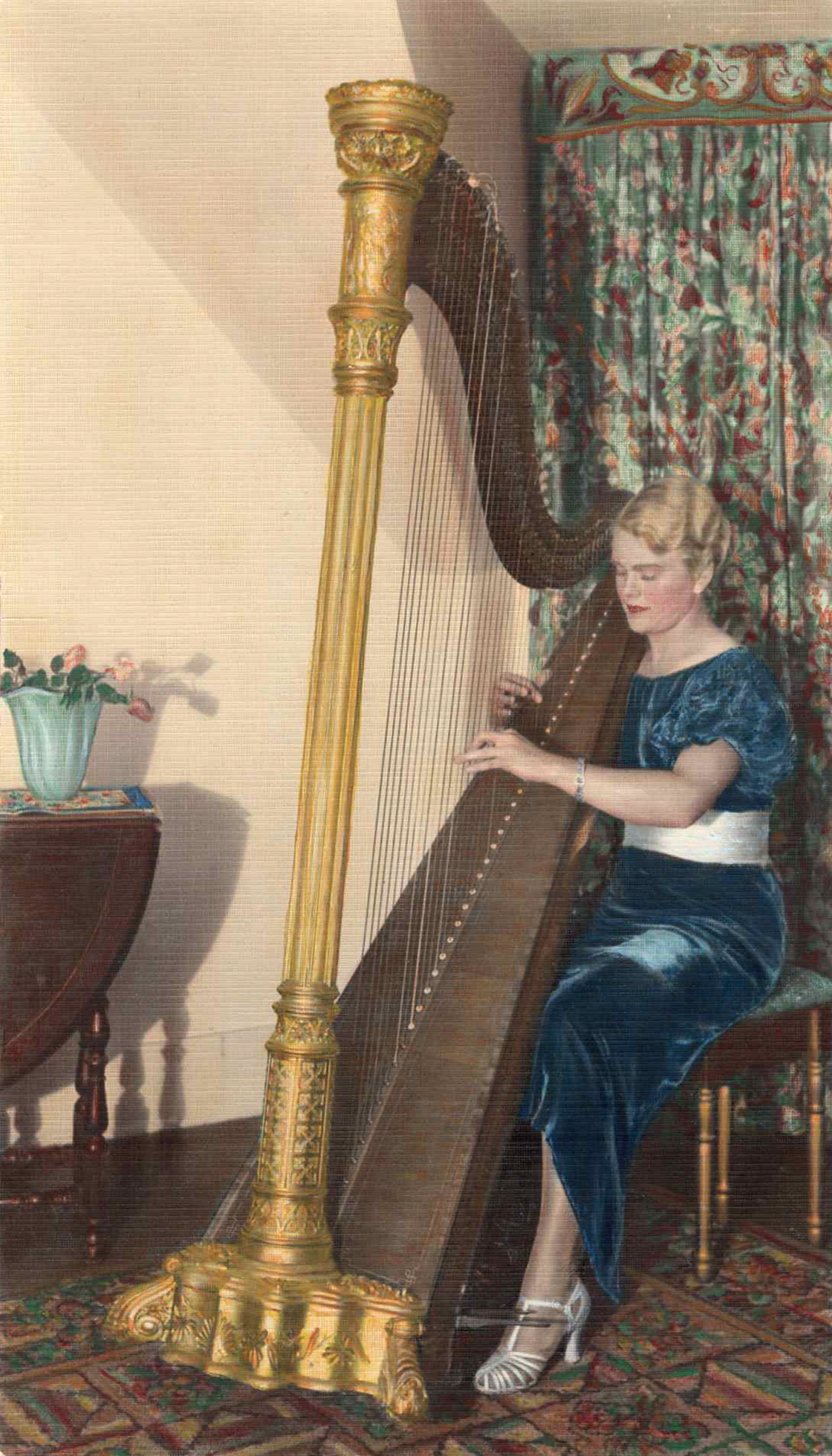

Joyce Rockwood

Writer

1907–1982

By Ruth Rudner

One cloudy day in 1954, Joyce Rockwood Muench was dusting bookshelves when a single ray of sun fell directly onto the spine of Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. Understanding it as a sign, she pulled the book from the shelf, opened it and read, “Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote ... .”

Chaucer had invited her on a journey into spring.

Her article, Pilgrimage Into Spring, was published in Arizona Highways in February 1955, then reprinted in the March 2018 issue. Reading her piece in preparation for my own article about spring for that issue, I was awed by the erudition I ascribe to anyone who reads Chaucer. (I never get very far.) I did, though, note that we shared the sense of adventure any journey into spring implies — a journey into the start of things.

We also share the last name of our photographer husbands. She is the mother-in-law I never met; I think we would have been friends. In 2018, Editor Robert Stieve liked the idea of including us both in the same issue.

Growing up in Two Rivers, Wisconsin, as the daughter of a college professor and the middle child of three, Joyce charted her own particular route through life. When her father accepted a job at the University of California, Berkeley, the journals she had already kept for years acknowledged her sadness at leaving close friends in Two Rivers but brimmed with excitement at spending her last two years of high school in Berkeley.

Like most literary teenagers, Joyce wrote poetry — poetry of longing, of exploration, of the search for meaning. Reading a notebook filled with her teenage poems, I was as moved by the intensity of feeling expressed in them as I was by the freedom in her writing to voice those feelings.

The notebook of poems was one of many packed in a box of Joyce’s journals, articles and unpublished stories. In another box, I found somewhat later writings, stories (labeled with the prizes they had won), typed copies of her journal entries, and tear sheets of articles written for Arizona Highways and other publications.

Most of her published writing was bylined Joyce Rockwood Muench, but she was a writer, if unpublished, long before she met Josef Muench. An experienced equestrienne, she and Josef met on horseback in a place called Happy Valley, California. (I’ve recently discovered this was an organized ride, although I prefer the version I’d imagined, in which the two of them, each alone on a horse loping across vast meadows from opposite directions, stop to chat. Finding they both are artists enamored with nature, they marry and go on to work together.)

I know nothing about their courtship. Nor does David, their son, which is probably as it should be. Although Joyce wrote pages and pages about a college love, I found only two journal entries connected to the relationship between Joyce and Josef. While she was in the hospital, producing her only child, she wrote, “I didn’t think it would be so hard to give birth.” This woman, imaginative and attentive to everything, had apparently not considered the reality of childbirth. (She did, however, have her journal with her.) A few days later, she wrote, “I love watching Joe hold the baby.”

Joyce was almost as excited about a new notebook in which to write as she was about the writing itself. “I like this journal so much!” she wrote. “As soon as Dad pulled it out of the box it looked interesting, and when he said I might have it, I knew it was to be my journal. I have a number of short stories I want to put into volumes. I have written some new sketches, and there are several that are waiting impatiently to be written.”

I understand the excitement of a new blank book — the anticipation of all that will go into it, the physical movement of a pen across the page, the reality of writing. Joyce’s image of herself was always that of a writer.

Which, on some level, makes it curious that at Berkeley, she majored in physical education. There is no one to ask how she became a gym teacher, although with Title IX, the landmark gender equity legislation, far in the future, it was one of the professions open to athletic women. Joyce was involved in her high school and college newspapers, too, and she continued to enter her stories in contests and record hopes and ambitions in her journals. But she never expressed a wish to major in literature or writing. She quotes from a letter written to her by “dear C.E.K.,” possibly a teacher: “I never wanted to dissuade you but wanted you to realize that there were two sides to majoring in Phys. Ed. … There is true joy in this field and not the smallest joy in being able to know and play with the girls. ... Please don’t get too highbrow ... it would be sad not to be able to converse with you. ... You must remember that Phys. Ed. did crowd out a lot of Thackery and Aristotle ... so keep a little bit of ordinary stock of conversation and thought around, won’t you?”

Joyce’s athleticism was useful when she and Josef began exploring the Sierra Nevada on pack trips. According to David — who was pulled out of school to go along but was required to write reports about the trips — they led donkeys and mules carrying their gear. Steep and rocky, the Sierras are terrain for serious hikers and adept riders. Kings Canyon, a favorite area for Joyce and Josef, requires skill and attention, both natural to Joyce. When Editor Raymond Carlson sent Joyce to Chiricahua National Monument for an Arizona Highways story, he called her “one of our most adventurous writers.”

Wanting her stories “out there,” Joyce entered them in writing contests, winning two first prizes, a second place and a couple of honorable mentions. She had bound a collection of stories on typewritten pages. It’s titled Prose, her name is printed under the title, and it includes work from 1922 to 1930. King’s Play, written in 1928, was awarded first prize — a book and $5 — in a 1934 contest. Another story, The Kut Sang, won first prize in a short story contest conducted by the literary society at Washington High School in Two Rivers in 1922, when she was a freshman. The award was $2.50.

The first page of this bound volume reads: “Collected in Santa Barbara, Calif., in the spring of 1936 from over a period of years and arranged more or less in the order written.” The spring of 1936 is close to the birth of Joyce’s only child, so it seems a natural time to be thinking of the work she had already produced.

Joyce was in her 50s when she left her marriage and moved to Arizona. In 1970 she wrote the editor of Arizona Magazine, a publication of The Arizona Republic, suggesting an article on dog training. College for Canines was, in fact, an idea close to the heart of this dog lover, but what strikes me is Joyce saying she hoped her name would ring a bell with the editor — that he had used work of hers when she was “the writing part of the Josef and Joyce Muench team.”

“I am now using my maiden name,” she continued, “and doing my own photography. I am living in Sun City and am completely sold on Arizona.”

In June 1972, Arizona Highways featured an article with Joyce Rockwood’s byline. I imagine the sight of her own name was liberating. Living in a time when married women generally used their husbands’ last names, and given that she worked on articles and books with her husband, Joyce certainly felt pressure to use his name. In several books written or edited apart from Josef, she remains identified as Joyce Rockwood Muench.

While most of Joyce’s articles are accompanied by Josef’s images, a couple feature David’s. I wonder how often that happens — a magazine article by a mother and son. (I also wonder if, in that case, she wasn’t delighted the two did share a name.) I think of her as Joyce Rockwood, a writer separate from her husband no matter how many articles and books they did together, no matter how many years and adventures they shared.

Her Arizona Highways articles, and those for other publications, were the product of good research plus lived experience. If she wrote about a place, she went there. I’m certain she was never without local wildflower or tree books as she wrote about the Arizona desert, Arizona’s mountains, Marble Canyon, Glen Canyon, California’s Sierras and much of the Southwest. She and Josef spent a great deal of time on the Navajo Nation, and although her writing about the tribe is “of the time” — by which I mean that while she and Josef had real friends among the Navajo people, they also viewed them as exotic — it also is respectful and caring.

Because she and Josef were close friends with Harry and Mike Goulding, proprietors of a lodge and trading post in Monument Valley, they spent much time there. In the September 1960 issue of Arizona Highways, Joyce wrote a piece about an Arizona road trip that covered virtually the entire state — which by then she probably knew by heart, so much time had she and Josef spent there. But she wrote with a special fondness for Monument Valley, which had become a tribal park two years earlier. And it was Josef’s photos, shown to film director John Ford, that influenced Ford to use Monument Valley as the location for many Westerns.

Joyce, too, would have fit right in as a cast member in Ford’s films. “Friday I went bareback riding,” she wrote in her journal on October 10, 1926. “I had quite a time getting Druscilla to canter, but when she began, she went like the wind.”

Could anyone have a more perfect image of their mother-in-law?

Carlos Elmer

Photographer

1920–1993

It’s not quite the Ansel Adams Wilderness — a section of California’s Sierra Nevada that honors another Arizona Highways Hall of Fame inductee — but Carlos Elmer’s Joshua View, an unassuming slope along Pierce Ferry Road north of Kingman, puts Elmer in the minuscule club of Arizona Highways contributors who’ve had a geographical feature officially named after them. At that spot and others in the area, the writer and photographer made countless photos of Joshua trees, an enduring subject of his work.

Kingman wasn’t Elmer’s birthplace — he arrived there from Washington, D.C., as a boy — but it was his hometown. In our May 1962 issue, he recalled his childhood of reading comic books at Route 66’s Hotel Beale, which was owned by his grandmother. Later, his interests grew to include more of Northwestern Arizona — a place where, he noted, a person often could go sunbathing at Lake Mohave in the morning, have a snowball fight in the Hualapai Mountains in the afternoon and be back in Kingman in time for dinner.

Equally skilled as a writer and photographer, Elmer quickly established himself as an Arizona Highways regular after his photos from Havasu Canyon appeared in our June 1940 issue. And over the next half-century, he pursued his craft while working first as a civilian U.S. Navy employee and later in instrumentation sales. He published his first book, Carlos Elmer’s Arizona, in 1967, and eight more books followed. And his photos and firsthand accounts of Lake Mead, the Colorado River and other destinations helped to publicize a relatively little-visited corner of the state.

Appropriately, Elmer’s last writing contribution to Arizona Highways, published posthumously in February 1994, was paired with his photo of Joshua trees near an old corral on the way to Grand Canyon West. “He was an extraordinary friend of this magazine,” Editor Bob Early wrote, “and will be greatly missed.”

— Noah Austin

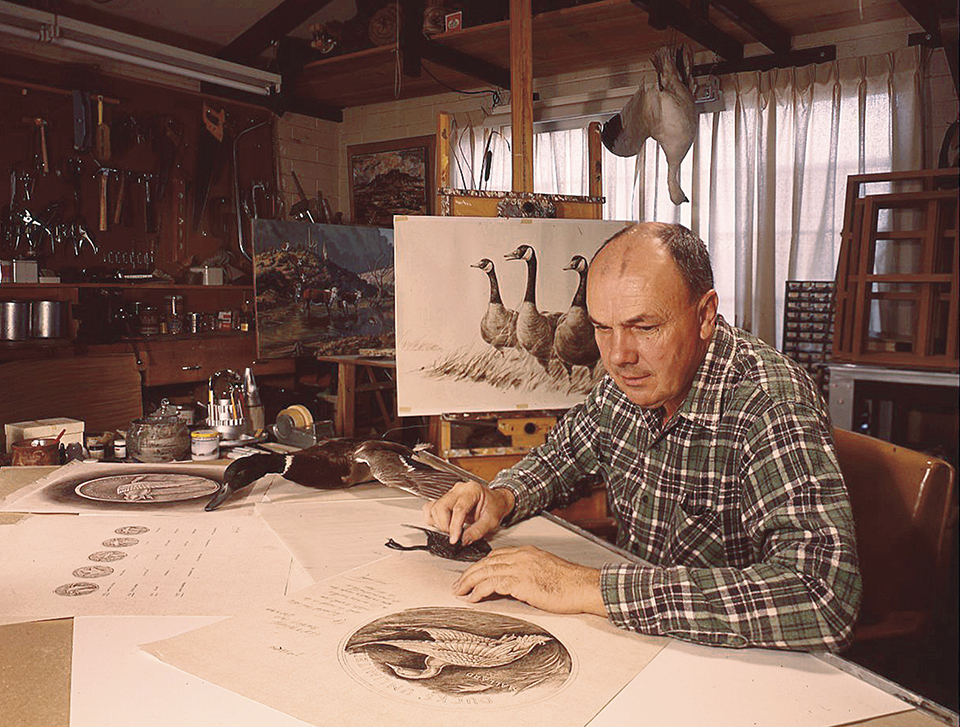

Larry Toschik

Artist

1922–2012

Perfect Illustrations. That’s how we titled a June 2013 portfolio of the work of Larry Toschik, who had died the previous year.

“In March 1967, Arizona Highways featured some paintings by an unknown artist named Larry Toschik,” Editor Robert Stieve wrote. “They were included in a story titled Larry Toschik’s Wonderful World of Birds, and the response was overwhelming. Almost overnight, Mr. Toschik went from obscurity to international recognition as one of the world’s greatest wildlife artists. Over the next two decades, we published nearly 100 of his paintings.”

There were red-tailed hawks and mountain lions, black bears and desert cottontails, along with a delicate, muted study of a duck with her ducklings on a placid lake. In August 1971, Toschik sketched the anatomy of a wildflower, along with hummingbirds, bees and other pollinators. And in February 1979, he carried the issue: front cover, back cover, and every page in between with Prowlers of the Clouds, a feature about Arizona’s eagles, hawks and owls.

For me, though, the February 1982 issue is particularly meaningful. It’s the issue of the magazine that corresponds to when I was born, and it’s a Toschik cover that celebrates migratory shorebirds — the plovers, killdeer and sandpipers that pass through Arizona on their way to their warm winter homes. In his editor’s letter for that edition, Gary Avey wrote:

“Larry’s love of nature is a lifetime affair beginning with his youth in Wisconsin. In the abundant wetlands of the northern latitudes he learned, through hundreds of frosty dawns, the majesty of Nature’s stage. Clouds of pintails wheeling over pink-tinged morning lakes nurtured the thrust of his art to express this great appreciation. For over two decades his artistry has appeared in the pages of Arizona Highways, in drawings, layouts and paintings. Whether depicting a tawny young mountain lion or a family of Gambel’s quail promenading through a prickly pear forest, his sensitivity and observation always reach out to his viewers.”

And that exacting work has made Toschik a member of our inaugural Hall of Fame class.

— Kelly Vaughn

Ray Manley

Photographer

1921–2006

Cottonwood born and Verde Valley raised, Ray Manley is one of three Arizona natives, along with Ted DeGrazia and Jerry Jacka, in our inaugural Hall of Fame class. And his familiarity with the state was one reason he seemed capable of photographing anything from an expansive view of Oak Creek Canyon to an intimate scene of cowboys around a campfire. “Some of the finest studies we have been privileged to present have been the result of his skill with the camera,” Editor Raymond Carlson wrote in our August 1956 issue.

Manley started making photographs in grade school; later, inspired by an Esther Henderson photo he’d seen in Arizona Highways, he acquired a 4x5 view camera and made some shots in the Flagstaff area. One of them, of the San Francisco Peaks, caught our editor’s eye and appeared on our back cover in October 1944, during World War II. The timing was fortuitous, as Manley had just completed U.S. Navy boot camp and was awaiting orders. His superiors saw his work in the magazine and sent him to the Navy’s photography school in Florida, where he became an instructor.

The change of fortune solidified Manley’s career path. After the war, he pursued freelance photography in Tucson before opening his own commercial studio there in the 1950s. The work left him plenty of time to devote to scenic photography, and he grew as a writer, too — among his stories for Arizona Highways were an in-depth piece on Canyon de Chelly and a look at how the Verde Valley had changed during his lifetime. And he wrote and photographed several books; the last of them, Ray Manley’s Navajoland, was published in the mid-1990s.

It’s his landscape work for Arizona Highways, though, that arguably is Manley’s most enduring legacy. Even today, some photographers use the term “Ray Manley sunset” to describe a stunning evening scene.

— Noah Austin

Jerry Jacka

Photographer

1934–2017

Jerry Jacka’s parents drove west from Chicago in a Ford Model A in the spring of 1929, finding the desert awash in wildflowers and beauty. With a tent and a few essentials, they began the long, slow process of homesteading 640 acres on the banks of the New River wash, setting saguaro skeletons into the rock and caliche to mark corners and burning the barbed bodies of teddy bear chollas to clear them from the land.

“Living on an Arizona homestead in the early 1930s was an arduous task which demanded days of back-breaking labor and scraping out a living by any possible means,” Jacka wrote in his 2011 book, Sun-Up Ranch: An Arizona Desert Homestead. “It was a tough life which demanded a sturdy pioneer spirit, a strong work ethic (and body), perseverance and fortitude.”

Born in July 1934, Jacka spent his formative years wandering the desert near his home, finding arrow points, grinding stones and other remnants of the Hohokam people who once inhabited the area. He went to school in a one-room schoolhouse, where he met his future wife, Lois, and learned to play the accordion. And then, in 1953, a man named Kermit Sanders posted an advertisement. He was hiring someone to go door to door in Phoenix to sell portrait packages for babies. Jacka got the gig, and a few years later, to further support his and Lois’ growing family, he became a deputy in the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office, all the while continuing to make photographs and quietly submit them to Arizona Highways.

In July 1958, his first photograph appeared in our pages. It was, in his words, a “god-awful shot of the Painted Desert,” made on his honeymoon. Over the decades that followed, he became a regular and frequent contributor to the magazine and eventually became Arizona Highways’ go-to photographer for shots of Indian art and artifacts. It was his consideration of detail that made him a great photographer. But it was his gentle persistence, his kindness and his humility that opened doors for him, particularly after his celebrated “pottery issue” in February 1974.

“The Hopis, the Navajos, they’re no different from you and me,” he told me for an article published in 2010. “The biggest bit of wisdom we learned from all of our time with them was respect. We respected them, and they respected us. We made some beautiful friendships.”

— Kelly Vaughn

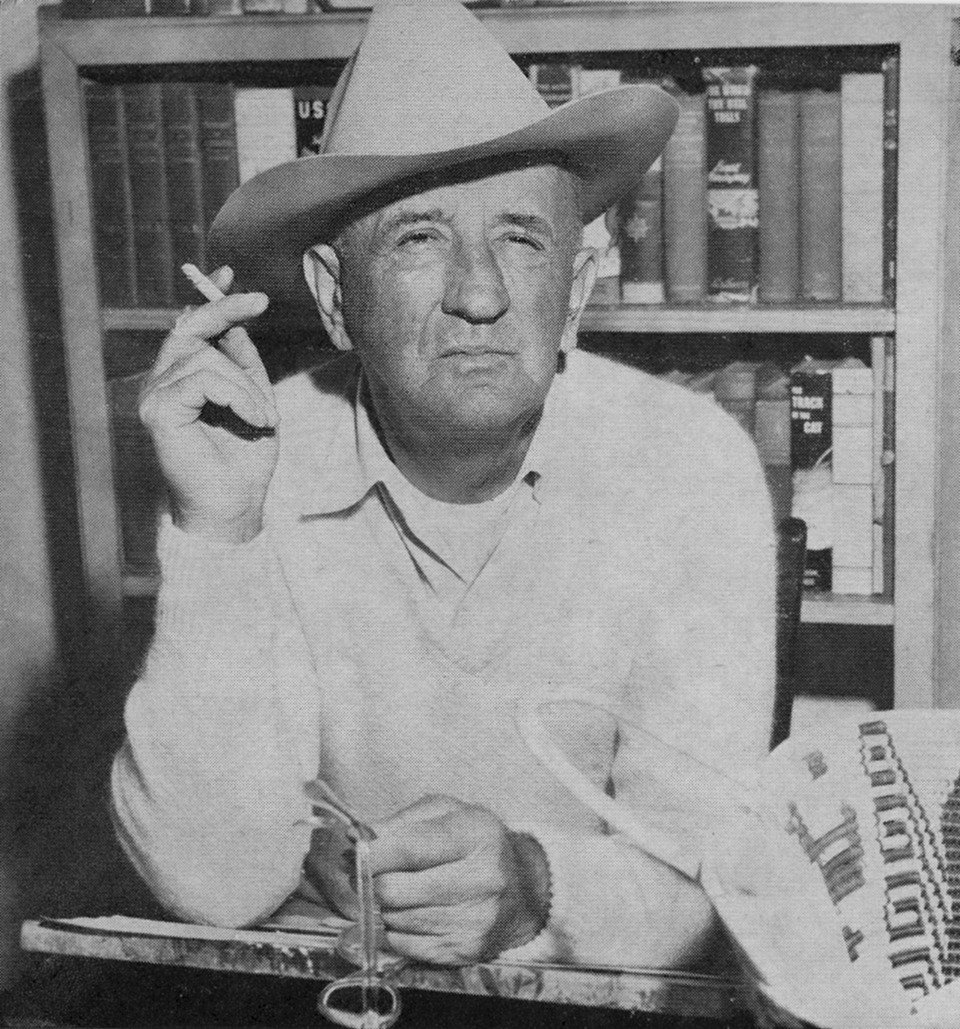

Ross Santee

Writer and Artist

1888–1965

By Kathy Montgomery

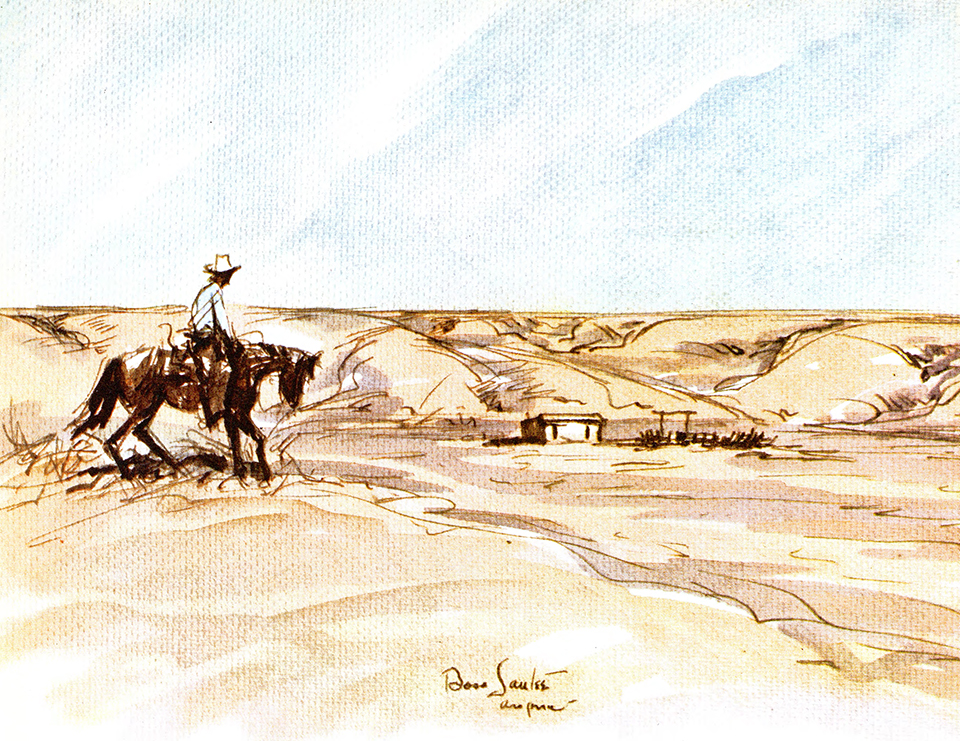

In a photo in a 1956 issue of Arizona Highways, longtime contributor Ross Santee leans forward, resting on his elbows. With a bookcase behind him, Santee squints as though scanning the horizon, cowboy hat characteristically tilted over his right eye, a curl of smoke rising from a hand-rolled Bull Durham cigarette.

At 6-foot-3 and 185 pounds, Santee embodied his nickname, “Slim.” One reporter described him as “sturdy as an oak, but gracious as a willow.” And like all great men, she observed, he was not readily recognized as such. “Most likely,” she wrote, “you’ll find him in the background somewhere.”

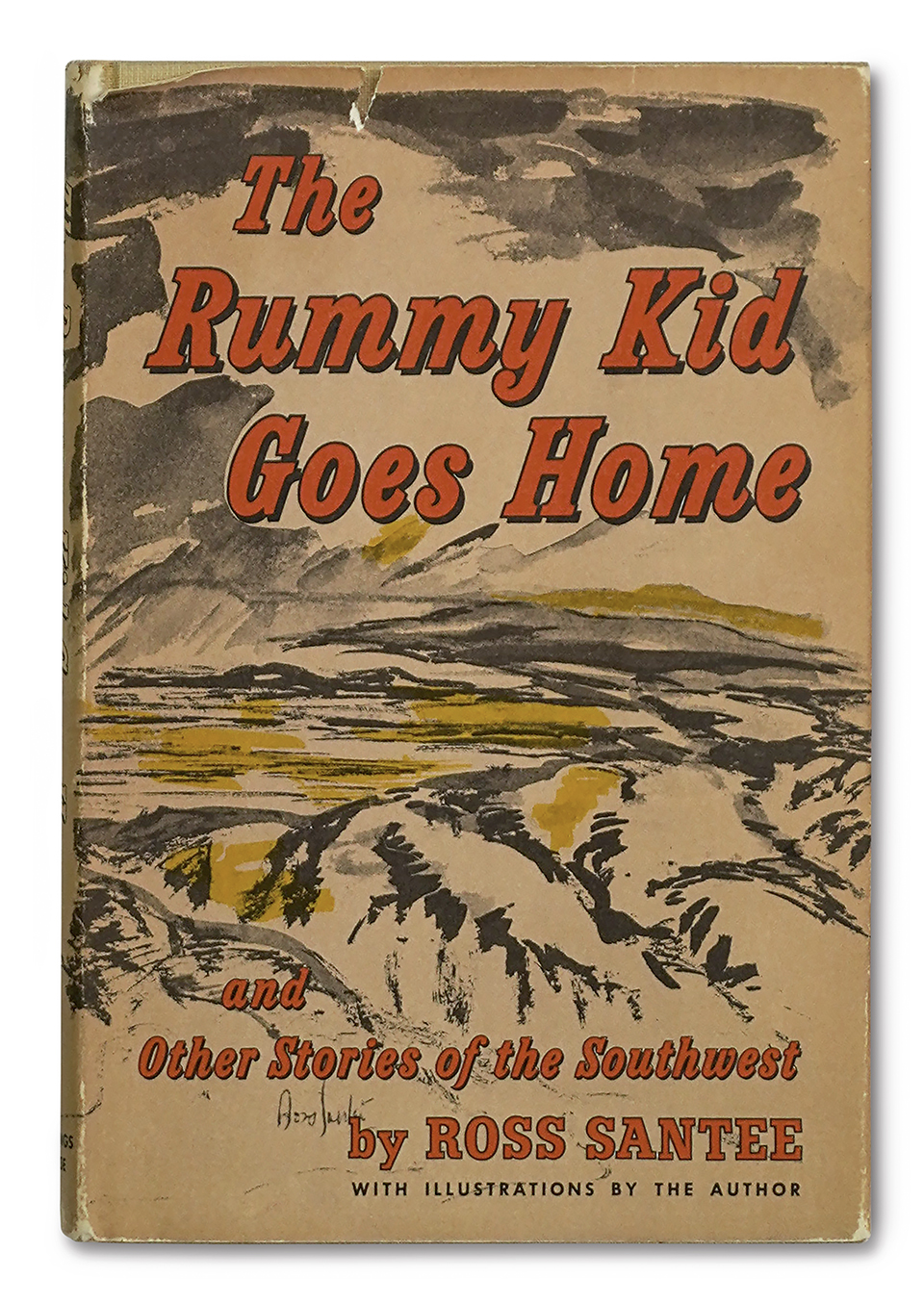

Among this magazine’s most notable contributors, Santee is part of a class of artists that includes Frederic Remington, Charles M. Russell and Maynard Dixon. But while his art was good enough to hang in the National Academy, it became secondary to his writing. The dozen books he penned included short story collections, novels, children’s books, nonfiction, a memoir and humor, and most of them were about cowboys, horses and the West. Reviewers have compared his novel Cowboy to Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. His short story Water, republished in Arizona Highways, won the O. Henry Award.

A Midwesterner by birth, Santee stumbled upon ranching and writing while aspiring to become a cartoonist. Yet he created some of the truest portraits of what he called “the West-That-Was.” And his contributions to Arizona Highways over nearly 30 years helped transform the magazine from what one commissioner called a “drab little journal of technical highway information” into an Arizona institution with an international reach.

Santee was born in 1888 to Quaker parents in the farming and ranching community of Thornburg, Iowa. Although he had no memory of his father, who died when he was 3, the town blacksmith told him “there was no horse he couldn’t ride or tame.”

Aside from requiring that he attend Methodist services on Sundays — Thornburg had no Quaker meeting houses — his mother left Santee free to pursue his interests, primarily hunting, sports and pool. While finishing high school in Moline, Illinois, Santee broke his nose playing football; later in life, the injury helped him appear to have been a lifelong cowboy.

But Santee also liked books, and he read everything Twain ever wrote. And although he failed art in high school — he recalled not being interested in “making copies of plants and flowers” — he liked to draw.

“Magazines were scarce in those days,” he wrote in his memoir, Dog Days. “At least, they were in our house. An’ about the only drawings I saw were John T. McCutcheon’s cartoons in the old Chicago Record. … His drawings interested me so much that when McCutcheon went over to the Tribune we switched along with him.”

About that time, Santee met his first “artist in the flesh,” a sign painter hired to do lettering on the local bank. It turned out, the painter knew McCutcheon, and he told Santee, “He makes a lot of money, too.”

“That settled it for me,” Santee wrote. “I’d be a cartoonist now for sure. For drawing pictures wasn’t work. An’ hard labor in any form had never appealed to me.”

While in Chicago to attend a football game, Santee wandered into the Chicago Art Institute and took in the student drawings that lined the hallways. “An’ when I found an original McCutcheon cartoon,” he wrote, “I knew I was going there to school.”

Santee paid for his first year’s tuition with traveler’s checks he won playing pool. “I thought three months would do the trick,” he recalled. “Maybe six.”

His first class began at 9 a.m. and lasted until noon, but at 11:30, he rushed off to his job in the cafeteria, which left him smelling like the day’s lunch. With characteristic humor, he wrote that a friend “finally quit because all the dogs followed him.”

Afternoon classes lasted until 4 p.m. Then, twice a week, Santee swept corridors and classrooms until 6. At 7, he headed for a job working backstage at a theater, which meant getting home around midnight.

Cartoon class met Fridays at 4 p.m. “We pinned our drawings on a line across the room, an’ the instructor criticized,” Santee recalled. “But most of the ideas we brought in had moss upon their backs.”

Like other students, Santee tried to imitate prominent cartoonists. “That was where I made my big mistake,” he said. “You can’t be someone else and get away with it.” He got fed up with cartoons — “hated the lousy things” — but didn’t have the nerve to admit he’d failed. After five years at the institute, he set out to make his fortune in New York and “damned near starved to death.” He added, “I knew my drawings were bad … for I wasn’t doing the thing I wanted to, an’ worst of all I didn’t know what that was.”

After a year, he’d had enough. Making a bonfire of his pencils, as one reporter put it, Santee vowed never to put pencil to paper again, except to sign a pay voucher. “I wanted to get as far away from pictures an’ people who drew them as I could,” he said. “So I took the first train West.”

Santee wrote about that trip in The West I Remember, first published in Arizona Highways in 1956. Western illustrations of the day featured close-ups of horses and cowboys, so Santee was unprepared for the vast expanses that rolled past his train window.

“The country itself dwarfed everything,” he wrote. “I couldn’t get enough of the big alkali flats or the mountains that appeared so close at hand and yet were many miles away.”

He found work wrangling horses at the Bar F Bar Ranch, near Globe. “It was a lonely job, but I liked it,” he wrote. “I wanted to be alone. For I’d failed in the thing I started out to do, an’ the less I saw of anyone, the better it suited me.”

He didn’t pick up a pencil for a year. Then, one day, he found himself sketching one of the horses on his chaps with a burned match. Eventually, he bought india ink and brushes and was making as many as 100 drawings a day. “An’ for the first time since I started off at school it was really fun again,” he recalled. “But each night before I took the horses in I built a fire an’ burned them up.”

About two years after arriving in Arizona, Santee included a sketch of the ranch foreman in a letter to an art school friend who worked at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. His friend showed it to his editor and wrote back to say the editor liked it and wanted more.

When the Post-Dispatch published his illustrations, Santee felt encouraged enough to return to New York, this time carrying sketches of things that interested him, done his way. After years of rejections, he got a friendly reception at Life magazine, where the editor who’d bought the first sketch he’d ever sold was working.

After Santee told the editor of another publication, Boys’ Life (now Scout Life), an anecdote about life on the ranch, the editor asked him to write it up. “Pictures cause me enough grief without taking on more misery,” he replied. But the editor insisted, then asked for another. And when an editor at Leslie’s Weekly asked if he’d published any writing, Santee said he’d just sold two lousy stories to a boys’ magazine. That editor “countered by asking me to bring him one of the lousy things,” Santee wrote.

Soon, the stories Santee was illustrating were his own, and he could afford to hang up his spurs. His success puzzled him. “Writing still comes hard to me, an’ I expect it always will,” he said. “The real fun in doing a story is drawing the pictures for it.”

It was the editor of The Red Book Magazine (later Redbook) who asked Santee to write a story about a drought, which became Water. The editor turned it down, finding it too unpleasant. So did almost every other editor in New York. Then Santee realized he hadn’t sent it to Collier’s, which published the story to great acclaim.

It’s not a coincidence that Santee married in 1926, the year his first book, Men and Horses, was published. His future wife, Eve, worked in a New York bookstore, and a friend had recommended the book. After a brief courtship, they married and built a home in Arden, Delaware, to be near an ailing family member. It remained Santee’s primary residence until Eve’s death in 1963, but they took frequent extended trips to Arizona.

From 1936 to 1941, the couple lived in Phoenix, where Santee served as state director of the Federal Writers’ Project — part of the New Deal-era Works Project Administration — and edited the Arizona State Guide. “For many of the kids on the project, it was their first job,” he wrote. One young writer recalled Santee had a flair for knocking “the gingerbread from a yarn.” Many of the project’s writers went on to have prominent newspaper careers.

“I really got more out of this project than anyone on it, I guess, because of the people I met and worked with,” Santee wrote. One of those was Arizona Highways Editor Raymond Carlson, who became one of Santee’s closest friends.

In 1936, Santee’s work began appearing regularly in the magazine, often accompanying stories credited to Federal Writers’ Project contributors. In the 1950s, Santee told a reporter the magazine was one of his favorite sketch outlets. “It isn’t like other magazines or newspapers that die tomorrow,” he said. “I’ve done a lot of work for that magazine, and I hope to do a lot more.” A decade later, he wrote to artist Philip C. Curtis: “Ray’s done quite a job with his magazine. … I don’t know how he survived all the pressures over the years.”

Curtis encouraged Santee to experiment with watercolor. “Phil also got me to paint in oil,” Santee recalled. “The damn medium had always had me buggered since it slipped an’ slid all over the canvas.” He figured out that by the time he’d smoked a cigarette, the paint would be dry enough to handle. “But,” he lamented, “I can still take pure color [and] make better mud out of it, I think, than anyone who ever tried the medium.”

Ted DeGrazia, another close friend, tried to get him to use a palette knife, but Santee couldn’t get a feel for it. “He was helpful in the fact that Ted uses simple colors,” Santee said. “Like myself, he gets confused if his palette is complicated.”

After Eve died, Santee returned to Globe. But less than two years later, in 1965, he died from a heart attack. A collection of stories he’d been compiling, all but two of them published in magazines years before, was published posthumously.

After Santee’s death, Carlson gathered a dozen of the cowboy’s closest friends on a knoll off State Route 77 south of Globe. On a trip to Safford, Santee had told Carlson he’d like to be cremated and have his ashes scattered there among the chaparral and mesquites.

Curtis and DeGrazia were there. So was Arizona Highways contributor Jo Baeza, whose book Ranch Wife Santee had illustrated, and Joseph Stacey, who later would succeed Carlson as editor. Each took turns scattering the ashes, which were mixed with rose petals.

A friend noted that Santee would have chuckled at the roses, adding, “Cow chips would have been more appreciated.”

David Muench

Photographer

Born 1936

“My fondest memories of working with Arizona Highways are the connections to Arizona’s diverse landscapes it has afforded me,” David Muench, who now lives in Montana, says via email. “But I guess that really means starting with Raymond Carlson, both as a warm memory and as the beginning of my long history with the magazine. I was still in high school when I accompanied my father [photographer Josef Muench] to meet him. Encouraging from that first meeting, he told me to send him something good and they would publish it. So, I was still in my teens when I had my first covers, front and back, thanks to him.”

That was more than 70 years ago, in January 1955 — which makes Muench this magazine’s longest-running and most storied contributor.

In the same email exchange, he says Toroweap Overlook is a favorite place to make images, particularly at sunrise. (June, when the sun is directly over the Colorado River, is ideal for this, he adds.)

“The photographs I made had to match the grandeur of the landscape with the most unusual light,” he says. “Making acceptable, and then great, images became a passion for me. I could not just ‘be there.’ I had to get into the feeling I wanted to convey. You could walk right into one of my images. To get it right, I would return again at different times. I needed to be present in the image.”

And that dedication is why Muench is among the inductees in our Hall of Fame’s inaugural class. “I think David was a true innovator in the world of photography — he saw and photographed Arizona unlike anyone who came before,” says Arizona Highways Photo Editor Jeff Kida. “People looked at his approach and began to emulate his style very quickly. Many of today’s scenic photographers have adopted some of David’s signature approaches to photography, and chances are, they don’t know why. Creatives like this are rare birds, and his impact on the visual evolution of the magazine has been enormous.”

— Kelly Vaughn

Jack Dykinga

Photographer

Born 1943

For the past 100 years, Arizona Highways has had hundreds of contributors. But only one has a Pulitzer Prize: Jack Dykinga. That accolade, in 1971, was the result of “his dramatic and sensitive photographs at the Lincoln and Dixon State Schools for the Retarded in Illinois.” Dykinga created the series while on assignment for the Chicago Sun-Times.

His career in photojournalism was incredible, but in his time contributing to Arizona Highways, he’s become one of the deans of landscape photography. After relocating to Arizona, he worked for the Arizona Daily Star in Tucson before leaving photojournalism in 1985. Three years before that, in November 1982, he made his debut in our pages — alongside the late Charles Bowden, who would become Dykinga’s friend and frequent creative collaborator. The piece, titled Ramsey Canyon: A Visit to an Unspoiled Land, featured nine of Dykinga’s photos.

“And lo and behold, up at Ramsey Canyon, I meet this abrasive, Fess Parker-looking guy,” Dykinga wrote in a 2019 tribute to Bowden in the Journal of the Southwest. “We circled each other like a couple of dogs peeing on a fire hydrant.”

In the more than 40 years since that first assignment, his work has appeared in these pages countless times.

“Jack Dykinga is a photographic dynamo who incorporates his journalistic roots into everything he shoots,” says Arizona Highways Photo Editor Jeff Kida. “All of Jack’s images come packaged with a story that allows viewers the ability to appreciate his work at a number of different levels. While he jokes about his success being the result of a 60-year apprenticeship, his work ethic is unparalleled. His photography has always been and continues to be the stuff most photographers aspire to.”

And not even a double lung transplant and double heart bypass in 2014 could threaten that. He survived, he recovered, and he wandered again into the desert to shoot. Sunrises. Sunsets. Saguaros. A family of burrowing owls.

“There are now five chicks in this burrow,” Dykinga told Matt Jaffe for the writer’s 2021 profile of the artist, It’s Time You Got to Know Jack. “They’ve been out for two days. Burrowing owls are 6 inches tall, but they punch way above their weight and think they’re eagles. They have a lot of attitude, and I have a special affinity for this group. This is the counterpoint to all the ugly stuff in life. You have to have that for yourself. It’s a refuge for the soul.”

As are Mr. Dykinga’s images for ours.

— Kelly Vaughn