Hard out of the small town of Harqua, Arizona, Flame Delhi was a natural.

“Born in the heat of the alkali country,” as one newspaper rhapsodized, Delhi stood over 6 feet tall and weighed in at a rock-hard “200 pounds of bone and muscle without an ounce of fat.” The pitcher’s nickname, like that of a sports hero in an old-timey novel, came from the wonder boy’s fire-red hair and equally fiery fastball.

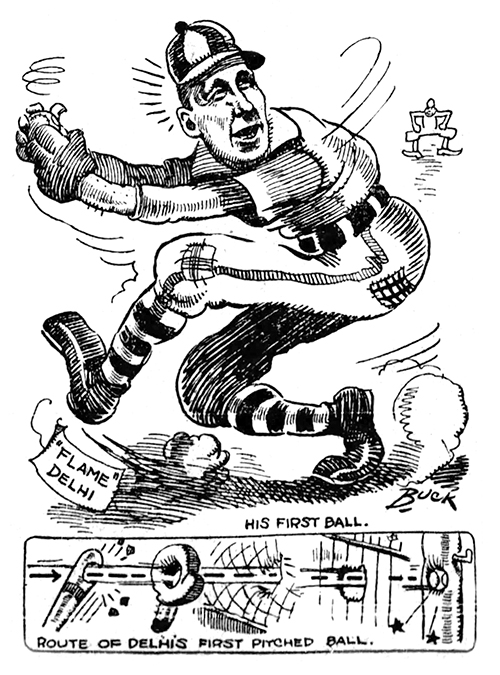

“They say out on the other side of the Rockies that all one can see when he turns loose the fast one is smoke,” one account read. Delhi also developed a devastating curveball and a dancing knuckler, and he further confounded batters with a long-striding delivery and by sometimes dropping from his overhand arm slot into a sidearm or underhand motion. “He has everything,” another description read. “His curves are as varied as an old maid’s moods, and his terrific speed and remarkable control are the marvel of the league.”

Still a teenager, Delhi was touted as the best prospect out of the Pacific Coast League in years. He earned comparisons to such all-timers as Walter Johnson, a 417-game winner and member of baseball’s inaugural Hall of Fame class, and Ed Walsh, the Chicago White Sox Hall of Famer who holds the record for the lowest career earned run average — and was the last pitcher to win 40 games in a season. Chicago baseball writer Sam Weller concluded, “It looks as if nature has predestined Flame Delhi to become great in the world of baseball. … He moves with the ease and grace of a lightweight boxer.”

On April 16, 1912, Delhi took the mound for the White Sox in the seventh inning against the Detroit Tigers. With that appearance, he became the first Arizona-born player in the major leagues. He was a can’t-miss phenom. Until he missed. Delhi gave up seven hits, three walks and six runs (three earned) over three innings. It was the only game he ever played in the majors.

For all the what-might-have-beens in Delhi’s baseball career, his story is one not of missed opportunities, but of opportunities seized. Because while F. Scott Fitzgerald famously said, “There are no second acts in American lives,” Flame Delhi would go on to prove that adage dead wrong.

came upon Delhi’s story the old-fashioned way: by using the time-honored historical research tool known as Google. While looking into Arizona baseball history, I searched “first Arizona major league player.” And when someone named Flame Delhi pops up, it grabs your attention.

Red hair and fastball notwithstanding, he was born Lee William Delhi (pronounced DELL-hi) in 1892. Delhi’s mother was from Fresno, California, and his Kentucky-born father — who served in the 181st Ohio Infantry Regiment during the Civil War under his original surname, Dolerhie — worked as a miner. The family moved to California when Delhi was 2 or 3, apparently after his father developed respiratory problems from his years of mining. But Arizona would later play a major role in Delhi’s post-baseball career.

Pitching for Santa Monica High School, Delhi showed early promise; then, in March 1909, he began playing for Merchants National Bank in the six-team Bankers League. Still only 16, he drew the attention of the PCL’s Los Angeles Angels. No average minor league, PCL baseball was so good that it was regarded as a third major league in the years before the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants moved to the West Coast. Some potential big leaguers even stayed in the PCL because of better weather, reduced travel and a longer schedule, which meant more pay.

The PCL season continued into late November, so Delhi joined the Angels in October 1909. Over the next two seasons, he pitched impressively, even dazzlingly at times. In 1911, he went 27-23, hurling a remarkable 445 2/3 innings, and set a record that stood for nearly 30 years by pitching a complete game in just 75 pitches. He also threw an 18-inning complete game against the Oakland Oaks, inspiring this Casey at the Bat-style verse from writer R.S. Boyesen:

The shades of night were falling fast

When through the town of Oakland passed

The home guard dripping salty tears

And seeking consolation beers.

As I looked into Delhi’s career, it became clear that Rodney Johnson’s 6,200-word article, posted on the website of the Phoenix-based Society for American Baseball Research (SABR), is the definitive account. Among the sources Johnson cites is a scrapbook assembled by Delhi’s daughter, Marjorie Prince. She put together articles and realia collected by her mother, then presented the scrapbook to her father on Christmas Day in 1941.

Johnson indicated that the scrapbook was housed at the Arizona Historical Foundation, but a quick search revealed that the foundation had closed. A source at Arizona State University’s Hayden Library said the foundation’s collections had been sent to other institutions and recommended checking with the Arizona Historical Society. But AHS records showed that the scrapbook had been returned to Prince, who died in 2008.

That’s why I find myself sitting in Johnson’s Tempe living room. With Prince’s permission, Johnson copied many of the scrapbook’s articles and photographs, and he’s generously offered to show me what he kept. The Delhi scrapbook items are just a small part of Johnson’s baseball reliquary, which also includes enough signed baseballs, vintage bobbleheads and cards — Sandy Koufax, Ted Williams and Mickey Mantle among them — to inspire unending envy in a late-stage boomer like me.

Johnson worked as the Arizona Diamondbacks’ official scorer for many years; his most famous call came in 2012, when he charged Chicago Cubs second baseman Darwin Barney with a throwing error. The call ended Barney’s 141-game errorless streak just three outs before Barney would have broken the major league record for consecutive errorless games at second. (Johnson stands by the decision.)

With an episode of the old TV Western Wagon Train on mute, we work our way through a litany of all that has gone to hell in the sports world since we were kids. Then, we talk Flame Delhi.

Johnson explains that the state’s SABR chapter wanted a name that represented both the organization, which is dedicated to historical research and statistical analysis, and Arizona baseball history. Chapter member Jim Vail went through The Baseball Encyclopedia to identify Arizona’s first major leaguer and discovered that Delhi held the honor.

“We wanted to learn more about Flame Delhi,” Johnson says. “I found Marjorie in a Bay Area phone book, and when I called, she was thrilled that somebody was interested. And, boy, she gave me all sorts of information. Sent the scrapbook, too. We had terrific conversations.”

Johnson calls Delhi “baseball’s Forrest Gump,” and he certainly had a knack for photobombing baseball history. During spring training with the Pittsburgh Pirates, he roomed with Honus Wagner — another of baseball’s original five Hall of Famers. And in the PCL, Delhi started and hit a home run in the game when Walter Carlisle, a onetime circus acrobat, made a tumbling catch, then completed an unassisted triple play — the only known such play by an outfielder in professional baseball history.

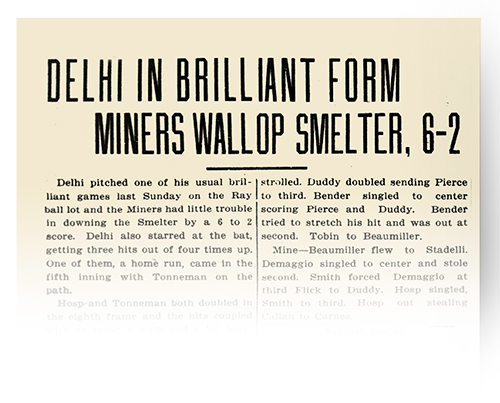

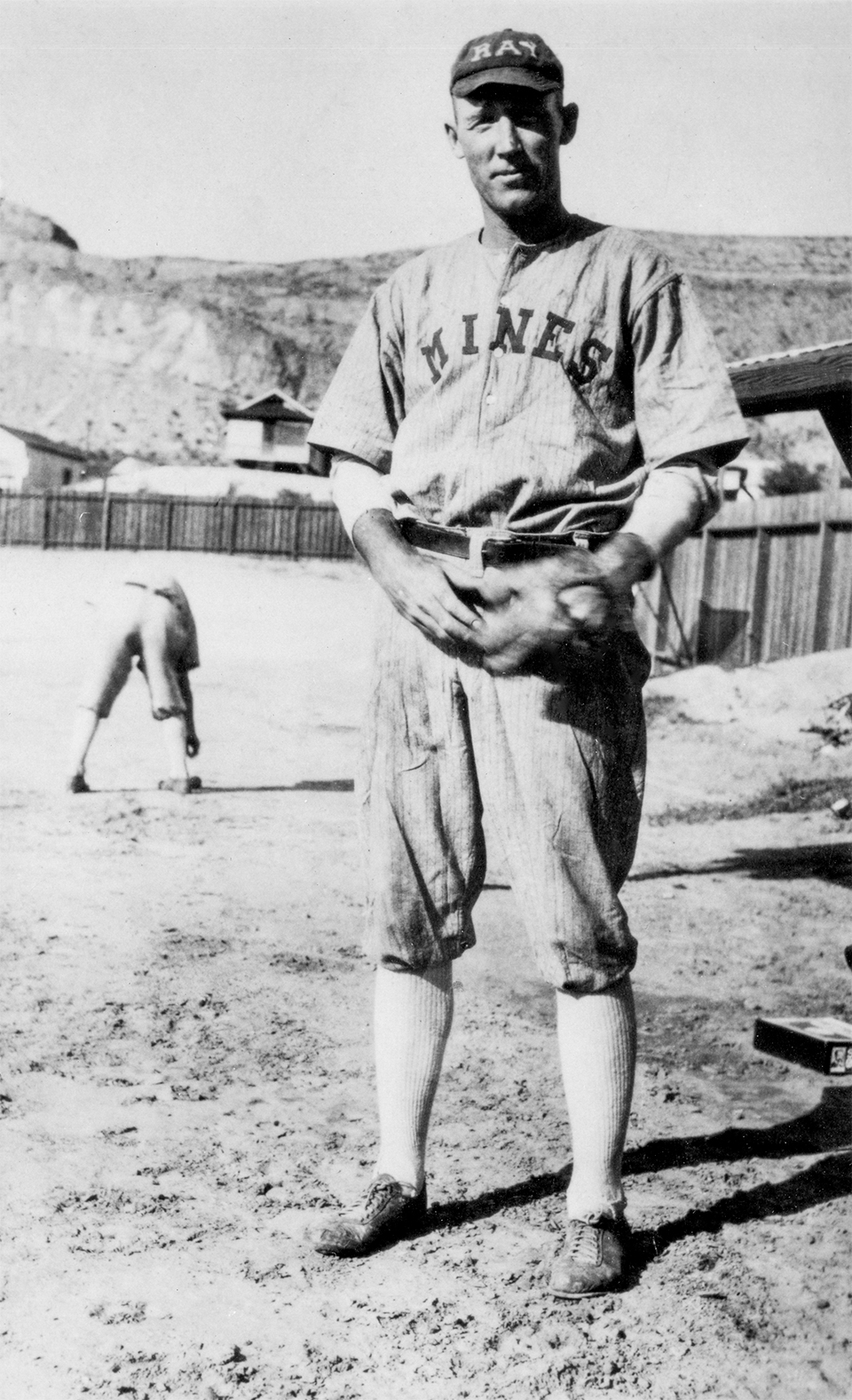

Looking through the materials, I come upon photos of Delhi’s days with the Ray Miners in Arizona’s Tri-Copper League, a short-lived but high-quality circuit of mining company teams. Still only 24 at that time, Delhi finished with a 14-5 record. I ponder why he didn’t try to return to the majors. “Flame Delhi was destined to be great,” Johnson says with a shrug. “But he had arm trouble. What really happened is that he hurt his arm.”

Throwing 445 2/3 innings at age 18 will do that to a kid.

It’s a fickle mistress, this game of baseball: Of the roughly 21,000 people who’ve played in the major leagues, more than 1,000 appeared in only one game. Members of this not especially coveted club include Tink Turner of the Philadelphia Athletics and Twink Twining of the Cincinnati Reds, who compiled ERAs of 22.50 and 13.50 in 1915 and 1916, respectively.

A few one-gamers did escape obscurity. Walter Alston struck out in his lone plate appearance for the St. Louis Cardinals but made the Hall of Fame after managing the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers to four World Series championships. And outfielder Archibald Wright “Moonlight” Graham played one inning for the Giants without coming to the plate but was immortalized in the baseball classic Field of Dreams.

As for Houston Astros pitcher Larry Yount, he felt a twinge while warming up for his 1971 major league debut and was yanked before tossing a single pitch in the game. Because he had already been announced, Yount received credit for an appearance, but that was as close to pitching in the big leagues as he would ever get. Compounding this tragicomic saga, Yount’s brother Robin played for 20 years for the Milwaukee Brewers, amassed 3,142 hits, earned two MVP awards and was a first-ballot Hall of Famer.

Delhi seemed destined for that kind of greatness. Even before joining the White Sox, his legend had grown. “There is a suspicion abroad that royal blood flows through his veins,” an account in The Cleveland Leader read. “He is descended from the Vikings and can trace his ancestry down to the time when history was only a blur.”

Another writer crafted a myth from Delhi’s desert origins: “His tiny bravuras first [seized] the sun-licked ozone of Arizona twenty-one years ago in a mesquite townsite several miles from Phoenix. … His parents were ‘poor but honest’ and connected with the finest families in the Territory. Nothing but the best mesquite-grass blood flowed in his veins. … All that the little ‘Flame’ knew about the world in those cactus salad days was cows, horned toads, castor oil and burros. His chief form of amusement was in tossing ground apples at slab-sided, long-horn steers.”

Everything was going Delhi’s way as he stepped to the rubber on that blustery Chicago afternoon. He wouldn’t even have to face Ty Cobb, another member of the original Hall of Fame class, because the notoriously surly Cobb had left town in a fit after being assigned a hotel room overlooking the train tracks.

Cobb or no Cobb, Delhi got rocked. About the best thing you can say about his appearance is that it hardly qualified as the world’s biggest disaster that week. If only because the Titanic had sunk the previous morning.

Unable to crack the talented White Sox rotation, Delhi returned to the PCL less than two months later, joining the San Francisco Seals. He struggled with wildness and went 5-8, albeit with a solid 2.72 ERA.

Because of arm troubles, Delhi considered trying out as a first baseman the next season, but after taking a pay cut to resolve a contract dispute, he kept pitching. His early starts were disastrous, and the press pilloried him. Calling “the red-topped Seal heaver” a “local calamity” after a 12-2 loss, the San Francisco Examiner declared, “We are inclined to suspect that personally Mr. Delhi is a most estimable gentleman. But as a pitcher — bon soir!”

After his release, Delhi went to Montana and joined the Great Falls Electrics. Still battling arm pain, he won 22 games (and hit .312 while occasionally playing outfield). He earned a spring training slot with the Pirates, then spent two years with the American Association’s Kansas City Blues, including a 21-15 season in 1915, when he pitched more than 300 innings.

Believing that his arm was the strongest it had been since 1912, Delhi planned to return to the Angels, but a clash over which team controlled his rights could have forced him to stay with Kansas City. Instead, he opted to pitch in the Tri-Copper League.

“Dehli Deserts to Outlaws,” the headline read, and if luck hadn’t always been on Delhi’s side, joining the Ray Miners was the best move he ever made — even if things weren’t always easy. Johnson describes how Delhi’s wife, Rose, used lard to grease the legs of Marjorie’s crib to keep centipedes from reaching the baby and how Delhi had to fashion a shower head from an old tin can and a garden hose.

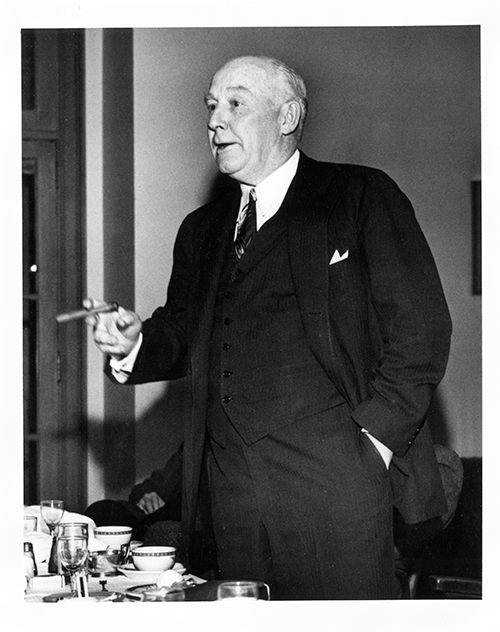

But it was worth it. The team promised Delhi the opportunity to learn civil engineering, and that apprenticeship set him on course to an impressive industrial career. He became a nationally known welding engineer and shipbuilder, working for 22 years at San Francisco’s Western Pipe and Steel Co., where he rose to vice president and led the company’s push to build more than 40 ships during World War II. Hailed as “a titan of Western steel,” Delhi earned $80,000 a year at a time when ballplayers averaged $7,500.

The can’t-miss kid had made it, after all.

As I later look at the articles I found at Johnson’s house, I come across one focused on Delhi’s post-baseball career. His red hair all but gone, he’s smartly dressed in a three-piece suit accessorized with a French-cuffed shirt and a pocket square. In the background, there’s a framed photo of him on the mound. Then, I notice he’s holding the baseball scrapbook I’ve been looking for.

Flame Delhi learned the game’s lessons well. “Baseball is the greatest field for the development of competitive psychology,” he once reflected. “No other sport allows so much room to come back. In a season of 152 games or more, a fellow can go into a batting, fielding or pitching slump and snap out of it in plenty of time to save that old average — figures that are as important to a ballplayer as those in his bankbook.”