Some places have water. Whole parts of the country leak from every pore and crack in the ground. Think of New Hampshire or the Pacific Northwest, where each little town has a glimmering river or stream. In Arizona, water takes on a different aspect. It is not everywhere. In the places it appears, it is a miracle.

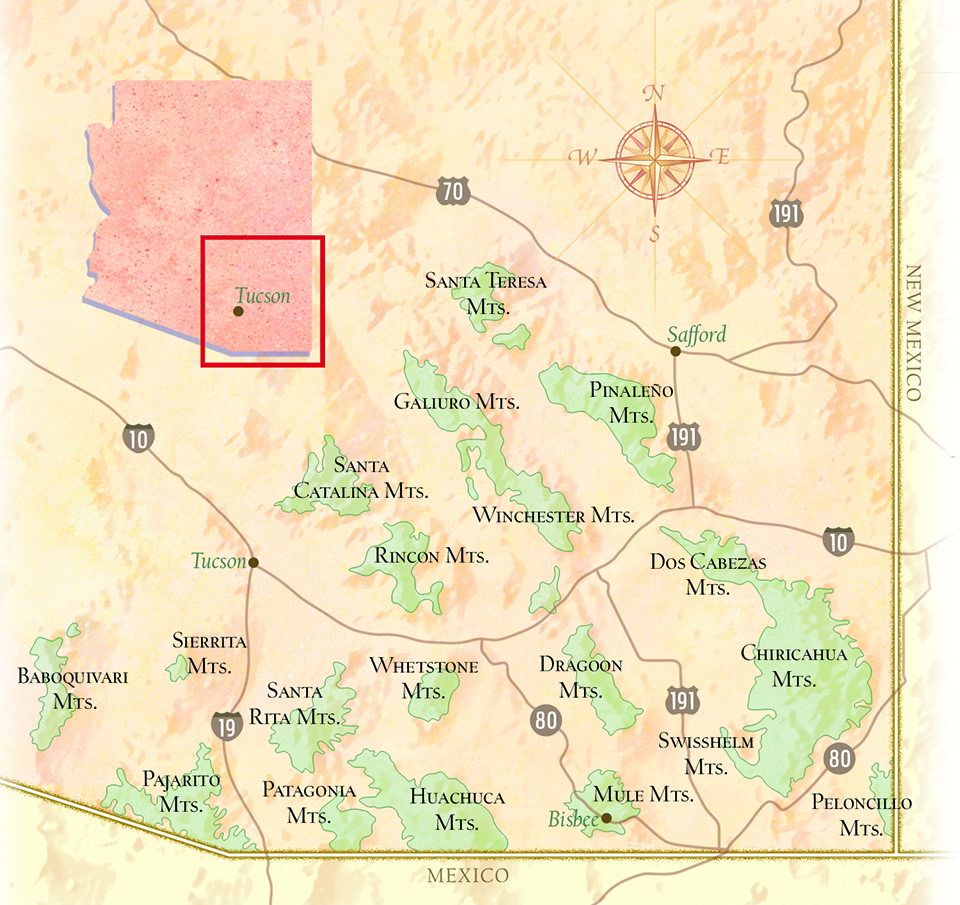

In my head, I map the land by its kinds of water — tinajas, seeps, springs, waterpockets, creeks, lakes and rivers. Each part of this state has its type, blood-red flash floods of the sedimentary northeast, and the hidden, underground streams of the dry, hot Southwest. Wherever there are mountains tall enough to wear pines and manzanitas, you find springs and courses of freshets and streams nearby. The phenomenon is most pronounced in the sky islands of the southeast quadrant of the state. Here, lone peaks and ranges stand out of the desert, the highest reaching almost up to 11,000 feet in elevation. Water pours from their bedrock innards. Gathered from storms and snowfall that collects around these solitary, weather-vane summits, this water reaches far down into the desert in the form of creeks spreading from the apron of the high-headed Pinaleños or the soft-spoken rises of the Whetsone Mountains. These are the miracles I speak of.

The solitary ranges in the lower right-hand corner of the state are called sky islands because they belong to a particular geographic class. They are pieces of high elevation standing well above surrounding terrain, their physical isolation separating them from any other similar biomes nearby. There are other sky islands in the world: Venezuelan “tepuis,” the Ethiopian Highlands and the lone Altai Mountains of east-central Asia, to name a few. The ones here are known as Madrean Sky Islands because they stem north out of the Sierra Madre in Mexico, forming steppingstones for migrant species of plants, animals and insects that can only survive by striding high above the desert. To the eye, these places are a powerful relief from the parched lowlands that close in around them like a sea of drought.

Another thing you don’t get much of in Arizona are fireflies. They are not entirely absent from the state — just rare. I know places, though, where the desert lights up like a celebration. If you go to the base of these sky islands at exactly the right time of year, usually in July when monsoon moisture begins to stir the air and days are brutally hot, you may see them. Follow the water. When you find these sky-island fireflies, it feels as if they’re pouring down from above, rivers of eerie, flickering light moving into dry country below.

Once, at dusk, I hiked to a creek along the edge of the Galiuro Mountains, two ranges east of Tucson. Most of the land was desert decorated with ocotillos, saguaros and fat thumbs of barrel cactuses standing absolutely still in the lingering heat of the day. The creek ran inside a forest. At 7:45 p.m., lightning-green lamps began to illuminate all along the watercourse. They filtered through tall bank grass, tiny lanterns lighting up leaf litter and pools of water. It felt more like New Orleans than desert. The creek formed a biological causeway, a place where small, sucker-mouthed fish live in the same country as javelinas, Gila monsters and sidewinders.

I walked up the winding hallway where cottonwood trees and alders formed an arched canopy, the air below swampy with plant sweat. As fireflies grew in number, I stepped out of the wooded stream to cut a bend by crossing open, rolling desert. Out here, there were no fireflies at all, and none of the heavy-drinking trees known as phreatophytes, with roots in constant touch with moisture. The air was as dry as a furnace. Ducking back into this breathy lair of dizzying lights, the difference was shocking. It seemed impossible, two different worlds that could never touch, the desert encasing this lush and languid creek fingering down from the mountains. My hands swept through spider webs freshly woven between pliant coyote willow switches. Fireflies became more numerous, and by 8 p.m., the path of the creek was wholly dazzled, their individual trajectories springing upward in meteoric strokes. I felt as if I were walking through shooting stars.

Walt Anderson, a professor at Prescott College and one of the state’s premier naturalists, has spent much of his adult life investigating these cloistered sky-island ranges. On a number of occasions, we have walked out here together, stopping at streams, listening for the chilling call of spotted owls. Anderson sees these islands as being a crucial part of American biology. He told me, “People often say that the Madrean Sky Islands archipelago is a unique bioregion, but I see it as a ‘biointersection,’ a meeting place consisting of dozens of mountain ranges that unify the spirits of the Rockies and the Sierra Madre, the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts.”

These mountains are an ecological connection between dark forests of the north and tropical habitats of the south. The toe of the Rocky Mountains nearly touches the top of the Sierra Madre, but not quite. The ecological bridge between these two continental regions are the sky islands, 27 of them in Arizona and New Mexico, and 15 in northern Mexico, where disconnected mountains are alpine at the top, and dry grasslands, desert scrub or oak woodlands at the bottom. I camped with Anderson one winter below the snowbound summit of Mount Graham, the highest point on one of the largest mountain masses among all the Madrean Sky Islands. It rises just outside of the town of Safford. At lower elevations, we’d walked along creeks crowded with alder, chokecherry, sycamore and dark Arizona walnut trees. There were raspberries and scouring rushes, plants that wouldn’t exist here without the elevation to support them. Higher in elevation grew Mexican blue oaks and wind-hushed ponderosa pines, and finally we slept on crusts of snow in a dense conifer wood.

Anderson told me that topographic diversity in the form of these high islands creates eddies and pools in waves of species dispersal. Their mere existence creates dramatically increased biodiversity, producing a wide range of habitats in a place that would otherwise be flat and dry. He said that as climates shift, species can weather changes on these mountains. Anderson sees time here in hundreds of thousands and millions of years where climates wash back and forth, and the sky islands act as both a refuge and an incubator for genetic futures. He told me that he knows a scientist whose research involved a 5-acre parcel high in Southeastern Arizona. On that piece of land, looking at only a type of moth from the macrolepidoptera branch, he found 950 species. These mountains are ridiculously rich — 5 acres of sky islands make up one of the richest biological patches of ground in the Southwest.

In the morning, I crawled out of my bag near the top of Mount Graham, pulling on layers of coats and pants in the frigid air. Striding slowly beneath the birdcalls and the drumroll of woodpeckers, I walked through the dense pines. Snow broke and crunched beneath my steps. Stout trunks stood from the snow, jigsaw pine bark and Douglas firs with gnarled, woody humps, burls and wind-flagged branches. I came to a clearing, a gulping space opening as the Earth fell away. It felt as if I were held up in the sky by magic. Beyond here stood other island ranges separated by lowlands of mesquites, prickly pears, chollas and soaptree yuccas. These other mountains rose like green thrones: the Dragoons, Swisshelm, Dos Cabezas, the Winchesters, the Chiricahuas, the Galiuros. Corridors of greenery flowed down each, dark tendrils moving into the desert, finally fading across the arid expanses below.

As the sun rose, tree shadows turned across each other. Anderson was up, and we walked through the woods, he naming off birds as he heard their calls. Chipmunks chased each other, scrabbling up pine bark, and Anderson watched them with binoculars.

“Chipmunks really illustrate the adaptive radiation of the West,” he said. “We’ve got 15 or 16 species of chipmunks in the West, and they’ve got one in the East. It shows that the West is topographically, climatically and vegetatively more island-like than the East.”

On Mount Graham, we were on the king of the islands. As the day warmed, snow began melting. Puddles ran into each other, sparking little streams, turning morning-frozen meadows to mush. This water would flow into the heart of the mountain and many years from now would appear in the desert below, perhaps giving birth to a flourish of fireflies. This is how miracles happen.