History’s been made many times at Rillito Race Track in Tucson. Unfortunately, history keeps repeating itself there, too. However, despite several efforts to demolish the historic buildings and sell off the land, local voters and a nonprofit have so far saved the 78-year-old racetrack.

By Kathy Montgomery | Photographs courtesy of Arizona Daily Star

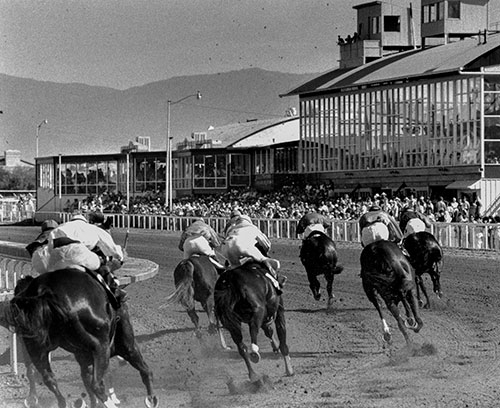

Spectators watch a race at Tucson's Rillito Race Track in the 1940s, before the track's grandstand was built.

Rillito Race Track stands like a time capsule along the banks of Tucson’s Rillito River. A historic oasis surrounded by modern development, the track and its burgundy-and-white grandstand look much as they did in the 1950s, the timeless outline of the Santa Catalina Mountains rising up behind them.

The history of the track is as colorful as the fans who still pack the grandstand for eight weekends most winters. In the 1940s, J. Rukin Jelks built a stud farm here, at the end of a dirt road. With fellow breeder Melville Haskell, he carved a rough dirt track that became the birthplace of formalized quarter horse racing.

Based on early speed trials held on Jelks’ track, Haskell wrote the regulations that gave rise to the sport’s rapid growth. Innovations at the track include the photo finish. And the nation’s fastest quarter horses competed at Rillito for top honors.

Today, the track is part of a county park with 11 athletic fields, including three inside the oval. Over the years, it’s faced pressures from soccer enthusiasts and developers. At various times, Pima County supervisors have considered demolishing Rillito’s historic buildings and selling the land.

So far, Rillito Race Track has beaten the odds. But with the current racing contract set to expire in June and the grandstand and clubhouse requiring millions in repairs, how it will look in the future is anyone’s bet.

So far, Rillito Race Track has beaten the odds. But with the current racing contract set to expire in June and the grandstand and clubhouse requiring millions in repairs, how it will look in the future is anyone’s bet.

*****

As American as the Stars and Stripes, quarter horse racing dates to Colonial Virginia, where horses raced down village streets or on short straightaways. Seldom run farther than a quarter-mile, the races came to be known as “quarter races,” while the fastest horses were “quarter running horses” or simply “quarter horses.”

Introduced to the Southwest via Anglo migration, quarter horses proved well suited to the rugged, arid landscape. Versatile and well mannered, they made ideal cattle horses for owners who often raced them on weekends.

Haskell called the quarter horse the “poor man’s racehorse,” because races required no special equipment or training, and could be run on any quarter-mile of level ground. And, unlike in thoroughbred racing, amateurs ran quarter horse meets. At Rillito, local breeders, cattlemen and sportsmen directed the races. An accountant ran the pari-mutuel department, and employees of local banks served as cashiers.

Jelks and Haskell came to Arizona within a few years of each other to recover from tuberculosis — Jelks from Arkansas in 1919, Haskell from Georgia in 1924. They bought neighboring cattle ranches in the Rincon Mountains; after his wife died, Jelks married Haskell’s sister.

Among the things they had in common, Jelks and Haskell shared an interest in horses. Haskell grew up on a plantation dedicated to raising and racing horses, and he and Jelks thought they could improve Arizona’s stock. Using the best thoroughbred studs they could find, they set out to breed a faster generation of quarter horse.

Jelks built his first racetrack in the Rincon Creek wash in the early 1930s. When it washed out, he carved another on his cattle ranch. There, Jelks and Haskell began hosting speed trials to show what their horses could do.

Jelks built his first racetrack in the Rincon Creek wash in the early 1930s. When it washed out, he carved another on his cattle ranch. There, Jelks and Haskell began hosting speed trials to show what their horses could do.

Around 1940, they helped Bob Locke build the Moltacqua Turf Club on Sabino Canyon Road. The following year, the Southern Arizona Horse Breeders’ Association held the first quarter horse speed trials at Moltacqua. By 1943, the top quarter horses in the country competed there for the title of “World’s Champion Racing Quarter Horse.”

By the time Locke sold the property that year, Jelks had sold his ranch and bought the stud farm, and he offered the use of his training track for racing. The Tucson Racing Association held the first organized races at Rillito in 1943. Two years later, the SAHBA and the Tucson Racing Association merged to become the American Quarter Racing Association, with Haskell and Jelks among the founding members.

By 1945, all quarter horse racetracks in the country had adopted Rillito’s regulations and course specifications: a straight, three-eighths-mile chute. During the 1947-48 season, Rillito installed a clock and a high-speed movie camera at the finish line, and the photo finish was born.

With these standards in place, by the 1950s, quarter horse racing had spread nationwide. Rillito was at the geographical center of the two established racing circuits, and the top horses from both met there each year to compete in the World’s Championship Quarter Horse Speed Trials.”

*****

Ironically, while the standards developed at Rillito were meant to ensure good sportsmanship, the track twice fell into the hands of companies with links to organized crime. Jelks sold the track in 1953 to an entity controlled by Peter Licavoli, a Detroit mobster who relocated to Tucson. A decade later, Emprise, a New York corporation with suspected mob ties, quietly assumed control of Arizona racetracks, including Rillito. Reporter Don Bolles was investigating the company in 1976 when a car bomb mortally wounded him.

Many of the current structures, including the grandstand and clubhouse, were built during Licavoli’s involvement, when the track was expanded for thoroughbred racing. But by 1954, Rillito’s ownership caught the attention of then-Pima County Attorney Mo Udall, and the company divested itself of criminal shareholders.

Many of the current structures, including the grandstand and clubhouse, were built during Licavoli’s involvement, when the track was expanded for thoroughbred racing. But by 1954, Rillito’s ownership caught the attention of then-Pima County Attorney Mo Udall, and the company divested itself of criminal shareholders.

The Pima County Sheriff’s Department took over the track after Licavoli’s company defaulted on its taxes in the early 1960s, and in 1965, the department conveyed it to Emprise. Emprise gifted the track to Pima County in 1971, a year before that company was convicted on a federal conspiracy charge.

In subsequent years, Rillito lost ground to modern racing facilities, sometimes shutting down for years at a time. In 1982, the Pima County Board of Supervisors voted to sell the land to developers, but a citizen ballot initiative saved it and preserved racing there.

By 1992, the track had become part of a multi-use public park with a growing number of athletic fields. In 2006 and 2014, county supervisors voted to tear down the grandstand to build more fields, but voters defeated bond measures that would have funded those plans.

The chute has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1986, and in 2010, a group organized to add the historic racing structures. With a background in preservation architecture, Jaye Wells saw Jelks’ stud farm as the key.

“This brought in the historic element, the cultural element, and it really did work,” Wells says. “That’s really what saved it — that and the downturn in 2008, when they couldn’t sell bonds.”

In 2012, the stud farm, grandstand and clubhouse were added to the NRHP as part of a historic district. Meanwhile, Wells and his partners formed the Rillito Park Foundation and negotiated an agreement to restore the Jelks house and develop the Museum of the Western Horse and Rider, incorporating Jelks’ memorabilia. The partners also won the racing contract in 2014.

In 2012, the stud farm, grandstand and clubhouse were added to the NRHP as part of a historic district. Meanwhile, Wells and his partners formed the Rillito Park Foundation and negotiated an agreement to restore the Jelks house and develop the Museum of the Western Horse and Rider, incorporating Jelks’ memorabilia. The partners also won the racing contract in 2014.

“Since that time, we’ve kind of made a peace,” Wells says.

As this story goes to print, the museum has received funding but is still in development, while the pandemic has made a 2021 racing season uncertain. Pima County Administrator Chuck Huckelberry says he can’t predict the outcome of the racing contract renewal. And while he says he’d still like to see the grandstand and clubhouse replaced by modern, multipurpose facilities, he doesn’t see the track or horse racing going away.

“It’s survived many other hiatuses,” he says. “The track will always be there.”

To learn more about Arizona's history, subscribe to our digital edition today for immediate access to the February issue of Arizona Highways.