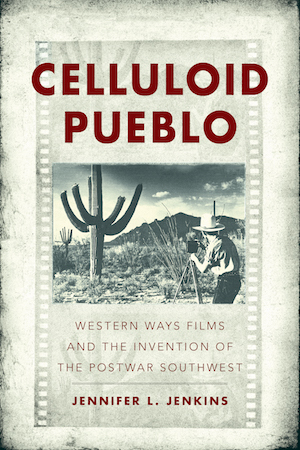

EDITOR'S NOTE: Today, we present a selection from the new book Celluloid Pueblo: Western Ways Films and the Invention of the Postwar Southwest, by Jennifer L. Jenkins. The book tells the story of Western Ways Features, which Charles and Lucille Herbert founded in 1936 to document the landscape, regional development and cultures of Arizona and the Southwest. To purchase the book from the University of Arizona Press, click here. See more photos from the book at the end of the excerpt.

In late May of 1929, Charles and Lucile Herbert drove into Arizona in an REO Speedwagon with 1200 pounds of motion picture and sound gear. Their primary assignment from Fox was to capture the sounds of the West with the new Movietone synchronized sound recording system which had debuted in 1928. For nearly three weeks they recorded Southwestern vistas, cowboy songs, Native dances and artisans, a Cowgirl beauty pageant, tourists at Grand Canyon, and 2000 head of bawling cattle—which the home office rejected because the deafening mooing, recorded by a sound truck parked in the middle of the herd, sounded artificial. (Hence the later need for Foley sound, so real sounds could be faked.) In 1929, the Herberts’ audio-visual documentation offered the nation and the world a fresh view of a mythic place in the public imaginary. Images of grand occidental landscapes and Native peoples defined the West in the U.S. imagination of the day, just as the cinematic West defined “America” for the rest of the world. The southern Arizona footage captures Borderlands activities in late spring: cattle round-up, cactus bloom, and warm days at the Indian School at Mission San Xavier del Bac. These subjects distinctively define borderlands Arizona by the picturesque trifecta of ranches, exotic flora, and Spanish colonial missions. This collection also includes craft films of Navajo silversmiths and weavers, sheep and goat-herding on the Navajo reservation, and footage of the Prescott-based Smoki Indian burlesque. The Herberts’ Arizona sojourn culminated in six reels of sound film about Grand Canyon. This 1929 footage, shot for newsreel appeal, records the sights and sounds of recreation and tourism, regional development and boosterism: in short, these reels illustrate the position of the West in the cinematic construction of Modernity in the final summer of the Twenties.

In late May of 1929, Charles and Lucile Herbert drove into Arizona in an REO Speedwagon with 1200 pounds of motion picture and sound gear. Their primary assignment from Fox was to capture the sounds of the West with the new Movietone synchronized sound recording system which had debuted in 1928. For nearly three weeks they recorded Southwestern vistas, cowboy songs, Native dances and artisans, a Cowgirl beauty pageant, tourists at Grand Canyon, and 2000 head of bawling cattle—which the home office rejected because the deafening mooing, recorded by a sound truck parked in the middle of the herd, sounded artificial. (Hence the later need for Foley sound, so real sounds could be faked.) In 1929, the Herberts’ audio-visual documentation offered the nation and the world a fresh view of a mythic place in the public imaginary. Images of grand occidental landscapes and Native peoples defined the West in the U.S. imagination of the day, just as the cinematic West defined “America” for the rest of the world. The southern Arizona footage captures Borderlands activities in late spring: cattle round-up, cactus bloom, and warm days at the Indian School at Mission San Xavier del Bac. These subjects distinctively define borderlands Arizona by the picturesque trifecta of ranches, exotic flora, and Spanish colonial missions. This collection also includes craft films of Navajo silversmiths and weavers, sheep and goat-herding on the Navajo reservation, and footage of the Prescott-based Smoki Indian burlesque. The Herberts’ Arizona sojourn culminated in six reels of sound film about Grand Canyon. This 1929 footage, shot for newsreel appeal, records the sights and sounds of recreation and tourism, regional development and boosterism: in short, these reels illustrate the position of the West in the cinematic construction of Modernity in the final summer of the Twenties.

Attention to exotica marks all of the Herberts’ Arizona Movietone films, which are aesthetically positioned between the stateliness of the past and the gawkerism of the moving image. Over and over Herbert visually quotes 19th century landscape painting and silent film, while adapting the frame to Modernist ideals through mechanistic technology. Sound is an amelioration and a curiosity, but the picture truly tells the story. So with Cactus Bloom. With remarkable economy, Herbert manages in eight shots to convey the scale and proportion of the saguaro cactus, the delicacy and appeal of the flowers, the comparatively verdant desert setting in which the cacti grow and bloom, and their statuesque command over humans in the environment. Even with the saguaro as subject, the god-in-nature sublime of the 19th century is scaled down, humanized and human-centered by the intervention of the motion picture camera.

The San Xavier footage shows the children at play in the schoolyard, a patio space originally built as a cloister for the adjacent Mexican Baroque mission church. The architecture of the space presents arches and finials to frame the shots, while the quadrangular layout of the patio presents natural linear perspective for composition. The playground contains a wooden slide, a swingset, see-saws, and a very low basketball hoop and backboard. Placed at the southwest corner of the cloister, the camera is well-positioned to pan the space, capturing the children as relaxed, laughing and truly at play. When the school-bell begins to ring, the recording capabilities of Movietone sound are evident. These decibel levels rival the Ronstadts’ cattle in sheer volume and intensity. As the bell-ringing continues, the nuns arrange the children in double lines to march past the camera to the classrooms on the east side of the playground. Experimental filmmaker Bill Morrison included this sequence in his pastiche of found film, Decasia (2002), using the nitrate decomposition on the film as an aesthetic element. The eerie Michael Gordon score, combined with the rippling images of black-clad nuns leading the children into the shadows, lends a sinister tone to the sequence in Morrison’s film. With original sound in place, this footage presents a lively group of youngsters returning to the classroom after recess. Herbert sets the frame at long shot and child’s eye level, recording the activity of a typical school day. He is particularly adept at fixed-camera work here, using pan shots to track the figures’ movement so naturally that it feels like a movement of the viewer’s eyes. Yet the camera remains in its corner throughout the sequence, which includes a scan of the play yard, the line-up and marching, and the children’s entry into their classrooms, cheered on by the ubiquitous reservation dog. The final shot is a vanishing point composition down the cloister arcade toward an arch that frames the Santa Catalina Mountains to the north. Franciscan Sisters stand on either side of the passageway, framing the arch that frames the vista, and reminding us of the Catholic containment of the transhumant Native peoples of the region. This is a classic Charles Herbert image, with foreground, middle, and background arranged in concert to create a complex and aesthetically meaningful image.

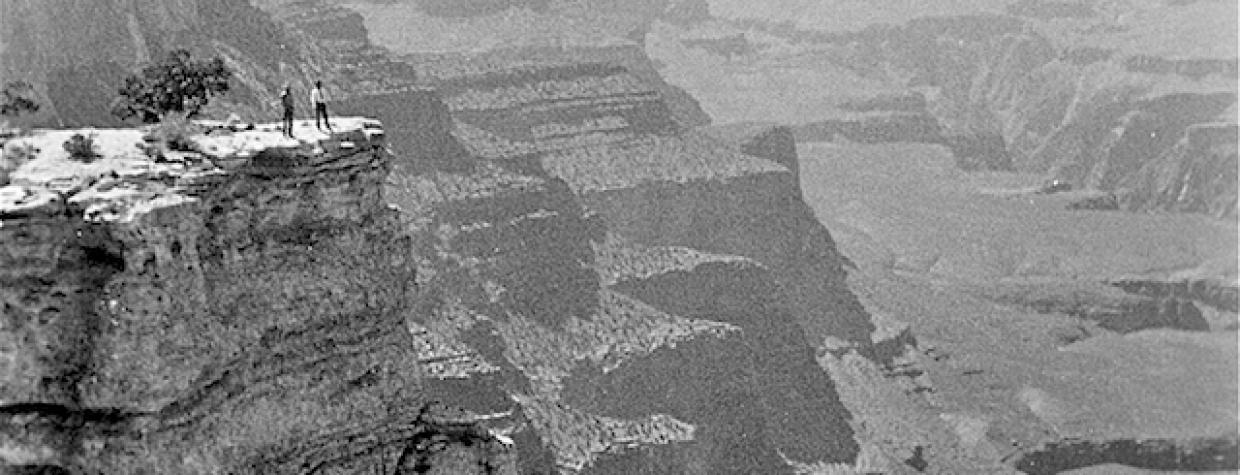

The Herberts’ time at Grand Canyon captured a specific period in history: June 2-14, 1929. Whereas many of the other Arizona films depict a somewhat timeless West, the Canyon reels are tied to specific events leading up to the opening of the first steel bridge over the Colorado at rim-level. The earliest reels show tourists boarding biplanes for Canyon flyovers and aerial tours. A few days later, the Herberts witness Native demonstration dances outside the Hopi House concession on the South Rim and follow tourists as they saddle up for mule rides. The final reel depicts the June 14, 1929 opening of the original Navajo Bridge. In all cases, the then-new process of synchronized optical sound captures unscripted comments from bystanders who were often unaware that their comments were being recorded. Unlike the more staged films shot in southern Arizona and along the border, the Canyon reels contain spontaneous crowd remarks that add a dimension of realism characteristically omitted by newsreel editing. These films offer a remarkable time-capsule glimpse of the Canyon during the final summer of the Roaring Twenties, when tourism was in full swing and visitors flew over, rode into, and drove across Grand Canyon.

For more information about Celluloid Pueblo: Western Ways Films and the Invention of the Postwar Southwest, click here.