Ritual transforms dried corn kernels into masa.

First, in a process known as nixtamalization, the kernels are soaked and cooked in an alkaline solution, then washed to remove any excess solution, as well as the outer husk. Grinding comes next — via food processors or hand-cranked grinders or molinos, traditional stone mills — and the resulting dough is known as masa. Masa harina is masa in its dry, powdered form.

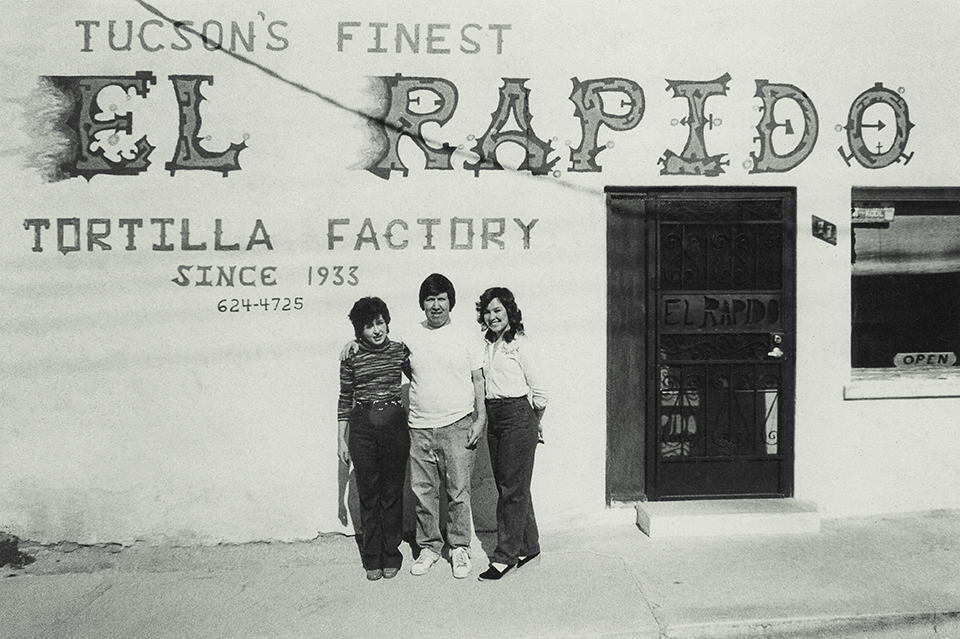

Such grinding is an ancient process deeply rooted in Mexican culture, having first been developed 10,000 years ago. And for generations between 1933 and 2000, a white adobe building, El Rapido, was the center of the corn-grinding universe in Tucson’s El Presidio Historic District.

This story is a look through the windows of that building, on which were painted:

GROCERY

EL RAPIDO MOLINO DE NIXTAMAL

MANUFACTURA DE TORTILLAS Y MASA

This, too, is a story about a woman, the great-granddaughter of the man who started El Rapido. This is a story about her family, and the tender thread that ties people together, and the big and small heartbreaks that tear them apart.

It took Melani Martinez more than 20 years to write The Molino, a memoir about her family’s home and eatery. What started as a project in her undergraduate creative writing course became a bold, immersive dive into memory, food and love. It became a reflection on faith, connection and the Sonoran Desert, where her family has lived for nine generations.

It became a journey into her family’s history, but more importantly, into their stories.

“When I first started recording the stories of my family, I had a feeling of: Why aren’t these stories in the world?” Martinez says. “But, really, there wasn’t an absence of stories. Borderland stories have been here for a long time, and they will continue to be around. Many of us near the border or in the families of people who are from these places, we’ve heard them and we’ll continue to hear them. The stories are not absent.”

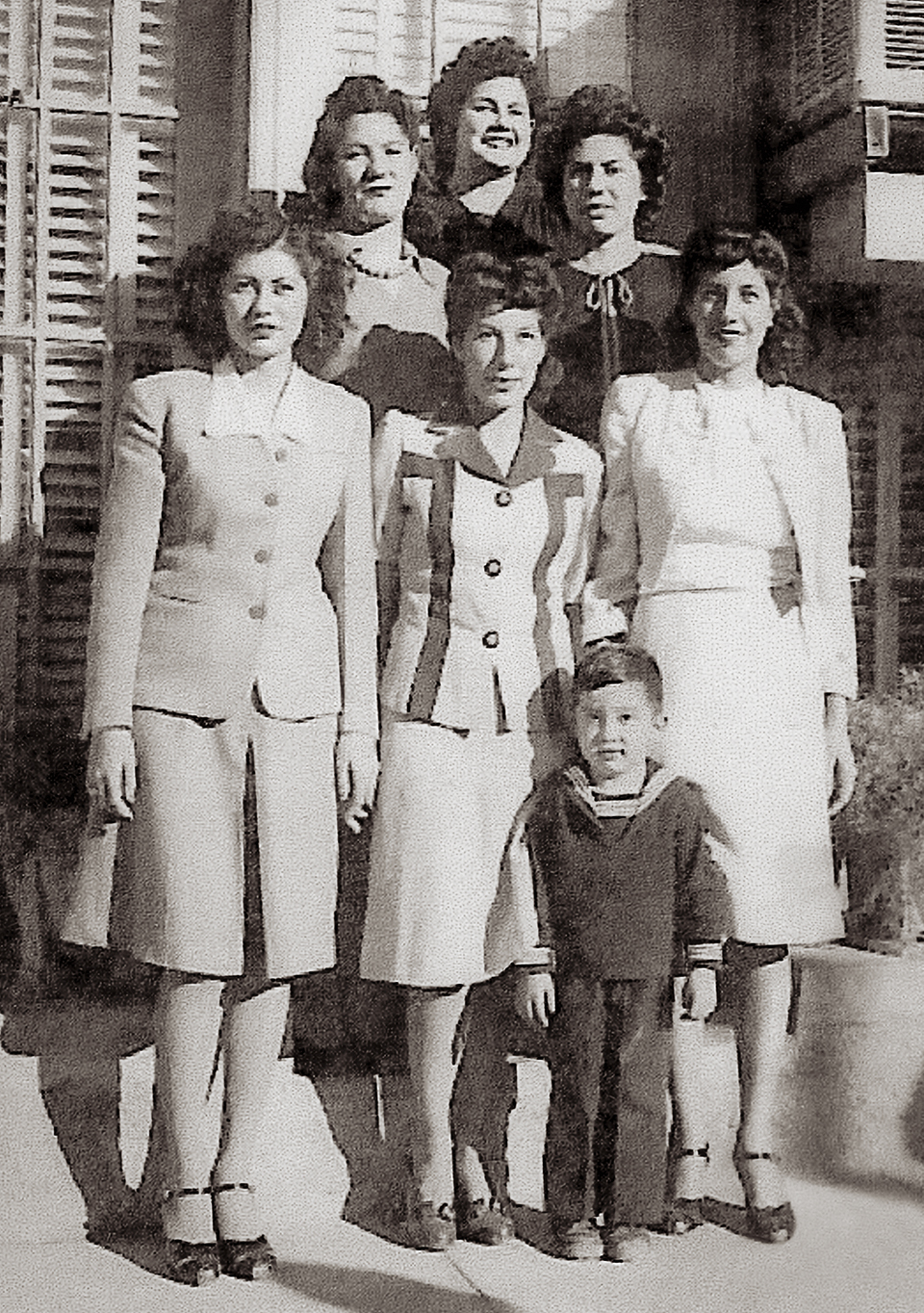

In 1933, at the height of the Great Depression, Aurelio and Martina Perez opened their corn-grinding factory, El Rapido. The family home — the Perezes had several children, including Martinez’s beloved grandmother, Juanita — was there, too, and the property occupied two addresses: 220 N. Meyer Avenue and 77 W. Washington Street.

“My best guess is that the building, the molino house where my grandmother grew up, must have been built around the arrival of the railroad, in the 1880s,” Martinez writes. “A Sonoran transformation of mud bricks next to the river and between the mountains.”

There, the Perezes ground corn for customers and prepared masa in the molino house. They also sold groceries, cigarettes and chiles. The couple made their own tortillas and tamales and started selling them to people in the neighborhood, too.

In the 1950s, the couple’s oldest daughter, Soledad Perez, took over the business. “She was one of the only women running a business in Tucson at the time,” Martinez writes. “She was a beautiful choir singer, single, strong, trailblazing and clever.”

When Soledad decided to marry in November 1976 — at the age of 62 — Edith Sayre Armstrong wrote a bulletin for the Arizona Daily Star: “El Rapido has been closed and you may have wondered why. Proprietress Soledad Perez found it necessary to shut down the tortilla factory for a few days to prepare for wedding Friday to Dolores Tarazon. … Patrons will be happy to know that it’ll soon be business as usual at El Rapido, but with the added attraction of Mr. Tarazon, who, by the way, plans to add chorizo to the menu.”

Sadly, Tarazon died just three years after the wedding, and Soledad came to terms with walking away from the business. Tony Peyron, Martinez’s father, took over shortly after her brother, Ricky, was born.

“I begin working for my father as soon as I can walk, talk and take orders,” Martinez writes. “Alongside my tía Micaela, my first task is to help make corn tortillas. Tía Mica feeds masa balls into a giant black machine lined with gas burners, and I stand on the other end of the conveyor belt to lift the toasty rounds off the belt and into a stack that can be bagged. This is my introduction to burned fingertips.”

Martinez worked with her father, brother and other family members as she inched toward adolescence, maneuvering childhood, friendships and the expectations of her Catholic faith while making deliveries and tackling her daily tasks at El Rapido. By high school, she decided she wanted out of the business, opting to go to the University of Arizona to pursue her undergraduate degree.

“I was working for my dad, and I had gotten a scholarship for all of my coursework, which was amazing,” Martinez says. “I didn’t know why I was supposed to be there, but I was the first person in my family to graduate from college, and I know they had a lot of expectations of what I would do and be, especially regarding income. After a couple of years of being at UA and not feeling like I fit in or belonged in any way in that space, I decided the only way I was going to be able to keep my scholarship was if I kept going to class. And the only way I could keep going to class was if I got to do something like creative writing.”

And in one of those writing classes, in the fall of 2000, creative nonfiction instructor Alison Deming encouraged her students to submit personal essays. Through that writing, Martinez began to truly understand the significance of her family’s business and the meaning of her childhood. She submitted her essay; a week later, she learned El Rapido, a casualty of gentrification, would close for good on December 24, 2000. (Today, the building houses a hotel and gallery, as well as a small space from which the Ceres pasta and coffee shop operates.)

Days later, Martinez was asked to read her piece aloud, in front of the class. Tears fell. And she decided to expand the narrative.

“For the first time in my life, I actually recorded something that was happening in the life of my family,” she says. “Then I realized how important that document was.”

In one vignette, Martinez recalls watching her uncle paint the mural that would long adorn El Rapido’s Washington Street-facing wall. She watched him use broad brushstrokes to create a painting of a man asleep with his back against a blooming saguaro, his face shrouded by the brim of his sombrero. Neighbors complained, citing the perpetuation of a tired stereotype of Mexican people, but Martinez’s father and uncle were unmoved. Now, when Martinez thinks of the mural, she thinks only of working, of grinding. The sombrero-wearing, two-dimensional man becomes a second narrator in The Molino.

Through another vignette, she shares her fear of the old house, where the relics that lived there were portraits of the ancestors who came before her. “I’m not sure if my father comprehended my fear and fascination with the old, dead things I was sure were living there in the floorboards,” she writes. “He never explained much of anything to me, and in school I was taught no history lessons that told this story, no definitions of these Presidio spirits, who they were, how they lived, ate and died.”

In more stories, Martinez explores grief and fear, love and separation, pain and triumph. She wrote those stories as she grappled with her own spirituality and pursued additional academic endeavors — a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing from Goucher College in Towson, Maryland, and an appointment as senior lecturer in the Department of English at the UA’s College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, where she teaches courses on borderlands-focused foundation writing and food writing.

Melani Martinez

“What was challenging was when I felt the pressure to remember everything on my own,” she says. “Then, when I tried the approach of what I learned was the right thing to do — the approach of interviewing my family — I realized that wasn’t really the way my family works. I felt like I was tricking them into speaking with me. Trying to capture what they were saying was really important to me, so I had to make the leap to: ‘This isn’t just my story. This has to be a collective story.’ ”

University of Arizona Press published The Molino in September 2024. Its cover features a photo of Martinez and her brother, Ricky, in front of the Washington Street mural in 1989. And its pages share memories from Martinez, her brother, her father and others who spent their days in and around El Rapido. The book and Martinez have received critical acclaim.

Still, she sometimes has a hard time calling herself a writer.

“I haven’t felt the courage to call myself a poet, even though I’m doing poetry,” she says. “I guess that’s how I define it. I’m doing this. I’m practicing this, as opposed to identifying myself as that person. I think, in a way, that’s self-preservation. If it really happens that I never write another book again, then I wouldn’t have hurt myself by calling myself a writer or an author. But I’m not sure if I really have a way of identifying myself as a writer, other than to say some of my highest values are embedded in what it means to be a writer in Tucson, in a place. Maybe even if I never wrote another thing, I would still have a lot to say about the place that I’m from and a lot to say about the other writers who are from this place.”

That’s the ritual of writing, maybe. Rinsing words in an alkaline solution, grinding love and strength and experience into phrases, then sentences, then paragraphs and pages. Sharing those words with family, with friends, with strangers and with the ghosts in the back rooms of our minds.