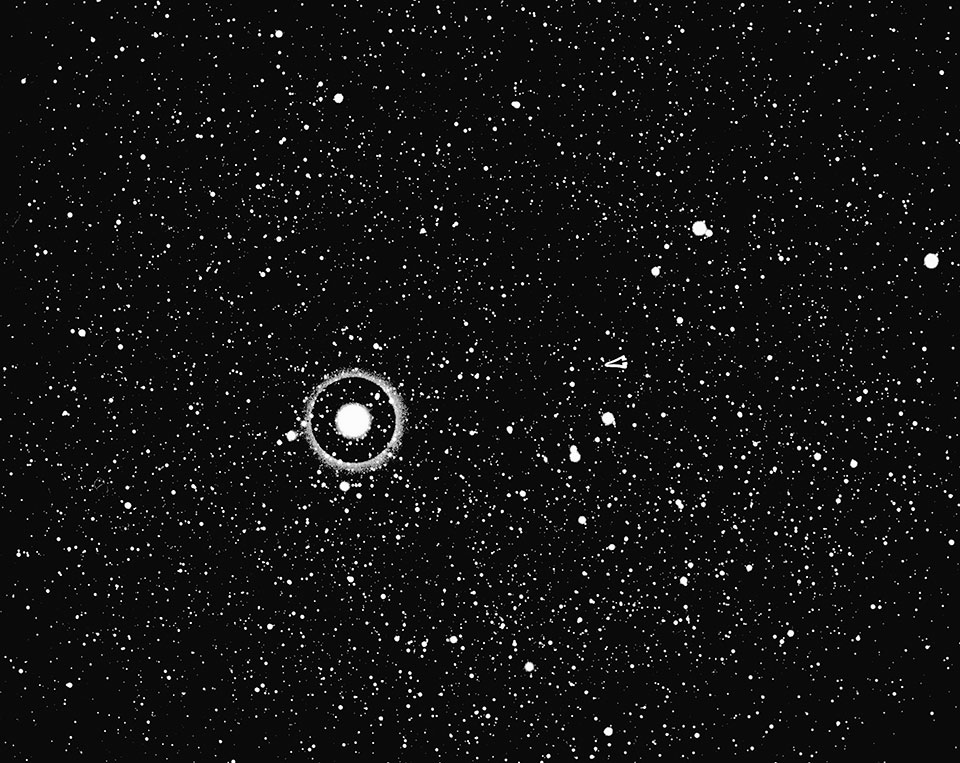

Looking through a hand magnifier, Clyde Tombaugh could barely see the stars on the image in front of him at Flagstaff’s Lowell Observatory. “My hand was shaking,” he later told his biographer. “I was literally shaking with excitement.” In less than an hour, he’d gone from doubt to certainty that a faint spot on the photographic plate was the hypothetical “Planet X” for which Percival Lowell had spent a quarter-century searching.

And for three-quarters of an hour, Tombaugh was the only person alive who knew where it was.

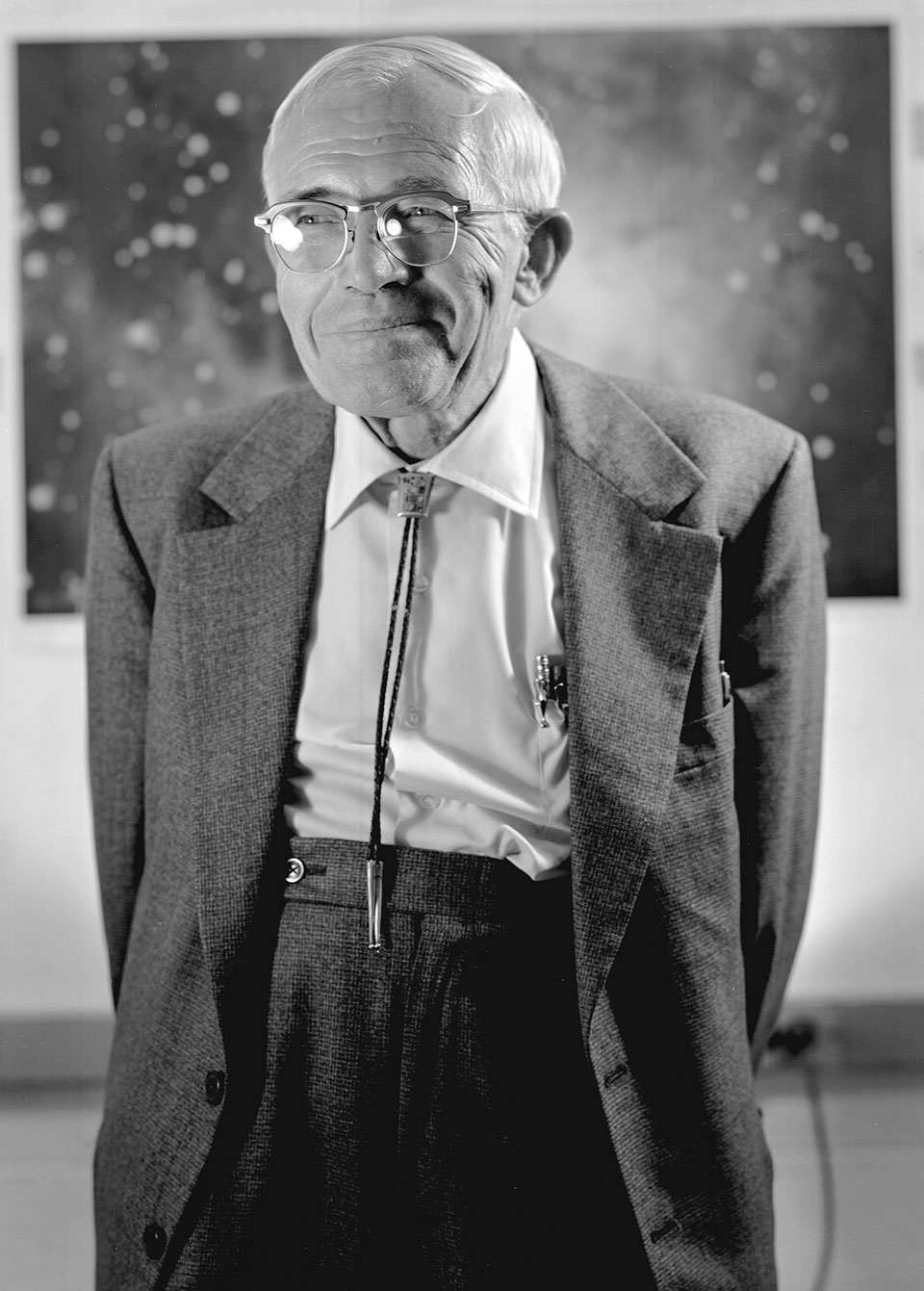

This month marks 95 years since the unassuming, 24-year-old Midwestern farm boy became the first American to discover a planet, personifying the notion that with talent and hard work, a person of any background can do something remarkable. For a nation descending into the Great Depression, it was something to celebrate.

Scientists now believe Pluto, the celestial body revealed on Tombaugh’s plate, was not Planet X. But in Arizona, neither Pluto’s later demotion to “dwarf planet” nor evidence of a theorized larger body has dimmed enthusiasm for what was, for decades, considered our solar system’s ninth planet. Lowell Observatory celebrates it every February with the I Heart Pluto Festival, and in 2024, Arizona’s governor signed a bill that ignored Pluto’s reclassification and made it Arizona’s official state planet.

Pluto’s designation remains controversial. But what’s beyond dispute is that Tombaugh’s discovery opened the door to understanding a “third zone” of the solar system. And it was just one of many accomplishments in a long and interesting career.

Born in 1906 in rural Illinois, Tombaugh worked hard on his family’s farm. By the time he was 11, he’d learned how to plant corn and cut wheat. And during the height of threshing season, he sometimes put in 16-hour days.

In high school, Tombaugh excelled in jumping, pole vaulting and baseball. Energetic and athletic, he built a tennis court behind the house and a football field in a pasture. He also dammed a creek to make an island-dotted pond for ice skating and miniature boat sailing.

After dark, he read. Beginning with the Bible and an encyclopedia, he moved on to his father’s trigonometry and physics books, becoming especially interested in geology and winning prizes at the county fair. To satisfy his own curiosity, he once calculated the volume, in cubic inches, of the distant star Betelgeuse.

Tombaugh’s brother Roy told biographer David Levy that he couldn’t remember a time when his brother wasn’t interested in the sky. His first look through his uncle’s telescope came around age 12, and he was thrilled to see the geology of the moon. By 16, when his family moved to Kansas, Tombaugh was obsessed.

After high school, he set about making his first telescope, grinding a mirror and sending it to a Wichita firm to be silvered. When the telescope manufacturer told him his mirror was poorly shaped, Tombaugh persuaded his father to help him build a tornado shelter long enough to use as a testing chamber. His second attempt was much better, and his third was good enough that the firm offered him a job. The offer was well timed: That summer, a hailstorm destroyed the family’s crops, ending Tombaugh’s college aspirations and desire for a future in farming.

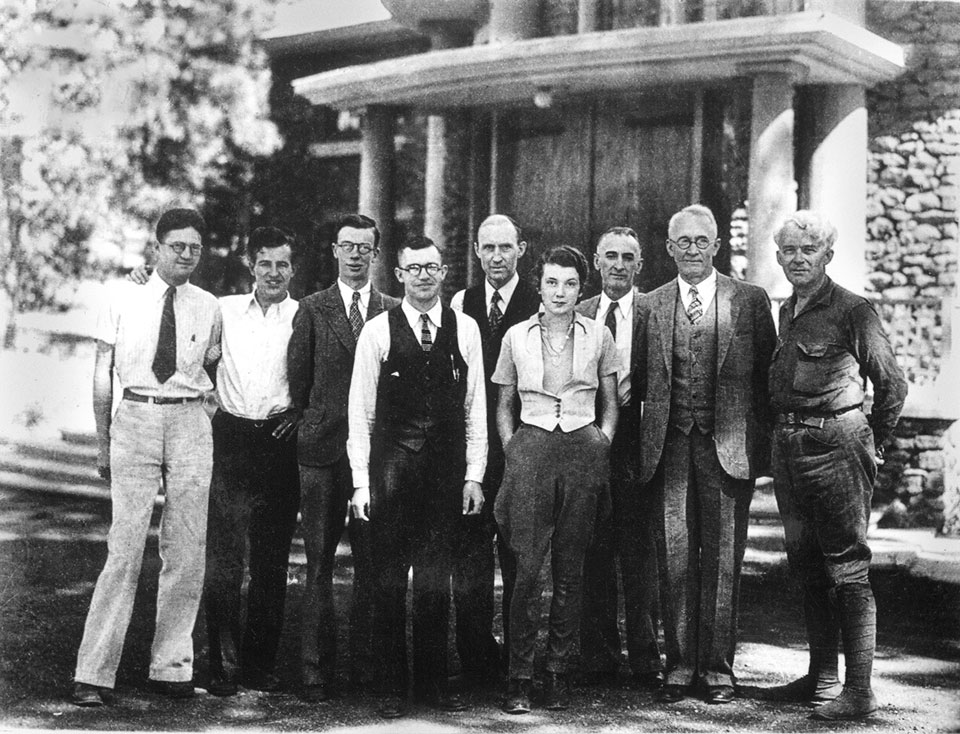

Then, he got an offer he couldn’t resist. Hoping for feedback, he mailed drawings of Mars and Jupiter to Lowell Observatory. To his surprise, the facility’s director, V.M. Slipher, instead asked whether he’d be interested in making images using the observatory’s new photographic telescope. The work involved long nights in a cold environment for little pay, and Tombaugh had to get there on his own for what might be only a 90-day trial. Tombaugh didn’t hesitate, booking a one-way train ticket — and departing with no money to return if it didn’t work out.

Today, many associate Percival Lowell with the eponymous Flagstaff observatory and his unsuccessful search for Planet X, but in his earlier years, he was known for his theories about Mars. Hailing from a prominent New England family, he’d started building the observatory in 1894 to study the red planet. Seeing what looked like an elaborate system of canals, Lowell concluded that Mars was inhabited by advanced beings with engineering expertise. He wasn’t the first to propose that canals or intelligent life existed on the planet, but he was criticized for those ideas.

Tombaugh also had been fascinated by Mars since childhood, and he wrote several papers on the planet during his career. He, too, saw what looked like canals where Lowell had described them, but he believed they indicated fault lines that released warm vapor, supporting vegetation. We know now that the “canals” were an illusion created by windblown dust. But Tombaugh did correctly theorize the existence of impact craters on Mars.

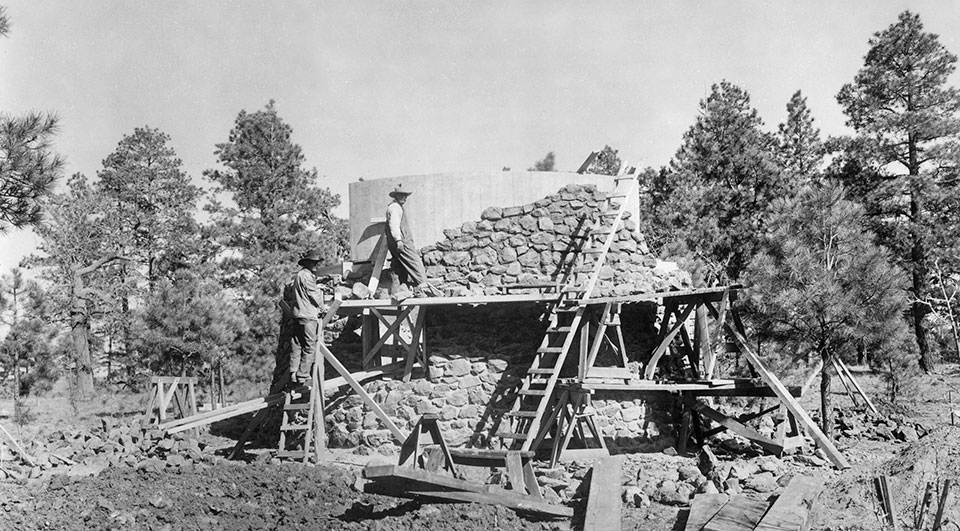

Lowell never stopped believing Mars was inhabited, but, stung by the criticism, he turned his attention to another idea of the time: that irregularities in the orbit of Uranus indicated an undiscovered planet beyond Neptune. Creating elaborate mathematical models to predict its location, Lowell in 1905 began a series of searches for the elusive planet, but his search ended unexpectedly with his stroke and subsequent death in 1916. The observatory moved on to more mainstream pursuits, and the search for Planet X didn’t resume until Slipher hired Tombaugh to begin again, perhaps hoping a discovery would improve the facility’s reputation.

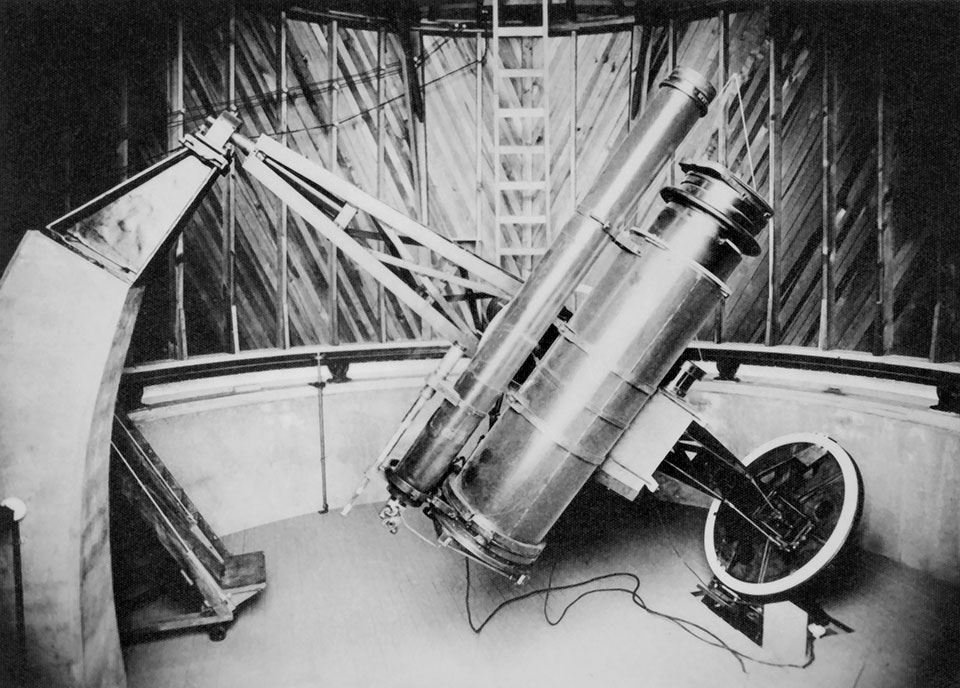

Slipher met Tombaugh’s train on an icy morning in January 1929 and showed him to his room on the second floor of the administration building. The lens for the new telescope arrived a month later, and Tombaugh made his first image on February 11. Slipher and his brother, planetary astronomer E.C. Slipher, examined the first images Tombaugh made, but by June, Tombaugh was solely responsible for searching the plates using a device that quickly alternated between two images made of the same part of the sky at different times, allowing the viewer to spot any changes.

The task was both mentally exhausting and boring, and at first, Tombaugh felt overwhelmed. As he did during threshing season, on the few nights each month when conditions were right for making images, he worked for 14 hours or longer. And it took time to figure out how to distinguish a planet from other objects. Yet, to everyone’s surprise, Tombaugh found what he was looking for just a year into his search.

Tombaugh later said astronomers make “discoveries that are in line with their personalities,” and his find is a credit to his thorough and meticulous nature. After the discovery, images of Pluto were found on some of the earliest plates Tombaugh had made and the Sliphers had examined, and even on a plate Lowell had made. Yet Tombaugh had seen what those experienced astronomers had missed, partly because they had been looking for something much larger to account for the effects on Uranus’ orbit. Pluto was too small, and when Tombaugh got his first look at it using a larger telescope, he reported feeling both moved and disappointed.

The observatory took weeks to announce the discovery, monitoring Pluto’s path to make sure. It eventually settled on Lowell’s birthday and the 149th anniversary of the discovery of Uranus. Just after midnight on March 13, Tombaugh joined V.M. Slipher as he sent the telegram. After that, some astronomers questioned whether Tombaugh had instead discovered an asteroid or comet. But when the orbit was finally calculated, there was no doubt.

That summer, Tombaugh went home to help his family with another harvest. When he returned, he resumed the search for undiscovered planets, finding hundreds of asteroids, two comets, a nova and a rich concentration of galaxies known as a supercluster. In all, Tombaugh figured, he examined about 90 million stars.

He took time off to finally attend college with the aid of his high school principal, who helped get him a scholarship at the University of Kansas. He returned to earn a master’s degree, completing a unique thesis that combined the study of the university’s telescope with its restoration. During World War II, the U.S. Navy asked him to teach navigation, a subject he first had to teach himself, at what later became Northern Arizona University. And in 1945, he took a sabbatical from Lowell to teach two semesters at UCLA, where he debated galaxy distribution with fellow astronomer Edwin Hubble.

In between, he continued his planet search. But when he returned from UCLA, Slipher unexpectedly ended his employment. He moved on to New Mexico’s newly formed White Sands Proving Ground (now White Sands Missile Range), where he pioneered procedures for photographing missiles in flight using long-focus telescopes. Predicting a future space station, he initiated a search for natural satellites that might be obstacles. He also captured some of the earliest images of Sputnik I, the first human-made satellite.

Having moved administration of the satellite search to New Mexico State University, Tombaugh remained there after it ended and established a photographic study of Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. And before retiring from the university in 1973, he created a doctorate-level astronomy program there.

Although Lowell Observatory initially downplayed Tombaugh’s role in finding Pluto, it was widely known by the 50th anniversary of the discovery. Tombaugh was honored around the country, beginning with the anniversary of the announcement in Flagstaff. On July 4, 1980, White Sands inducted Tombaugh into its Hall of Fame, and in October, the University of Kansas dedicated the Tombaugh Observatory. A few years later, at age 80, Tombaugh embarked on a national fundraising tour for a fellowship established in his name at New Mexico State.

David Eicher, then a young editor at Astronomy magazine, recalled that in his later years, Tombaugh was stooped and somewhat frail, but “absolutely hilarious” and full of rapid-fire puns. “He was quite a guy,” says Tombaugh’s son, Al. “He was a very kind person. Both he and my mom were probably the most honest people I’ve ever known … and he was completely dedicated to whatever project he was involved in.”

Tombaugh died in 1997, years before Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet, but the controversy was brewing during his lifetime, and he shared his feelings about it with Levy. “I know it’s coming,” he said. “And I hate it.” His daughter, Annette, recalls, “He was very hurt that this was happening,” and she calls it fortunate that her father wasn’t alive in 2006, when the International Astronomical Union’s vote took place. It was also fortunate, she says, that the New Horizons probe to Pluto had launched before the change. “Otherwise, that mission never would have gone off,” she says. “It affected our family. Fortunately, it did not affect the mission to Pluto, which was highly successful.” She and other family members were there to see the spacecraft launch with some of her father’s ashes aboard. “That was a real high moment in my life,” she says.

The images New Horizons sent back in 2015 revealed a far more interesting planet than anyone had imagined. Five years later, on the 90th anniversary of Pluto’s discovery, mission principal investigator Alan Stern said, “I only wish that Clyde had lived to see all that New Horizons discovered and how stunningly beautiful Pluto is.”

Annette recalls packing for a trip when her husband called her over to look at the images and she saw a distinctive heart-shaped region on Pluto’s surface. “I said, ‘That’s the message — that I still love you guys,’ ” she recalls.

“The discovery of Pluto put Flagstaff on the map in a lot of ways,” says Kevin Schindler, a historian at Lowell Observatory. “It also helped set the foundation for future studies at Lowell, because virtually every major discovery related to Pluto has connections to Flagstaff’s Lowell Observatory. Even if you say it’s not a planet, it’s a prototype of a whole new type of body in the outer solar system we never knew about before. It changed how we see space. I think that’s a neat thing to celebrate.”

For more information about this year’s I Heart Pluto Festival at Lowell Observatory and other locations in Flagstaff, visit iheartpluto.org. For more information about the observatory, visit lowell.edu.

A previous version of this story misidentified a group of galaxies Clyde Tombaugh discovered. Such a group is known as a supercluster, not a globular cluster. We regret the error.