When it comes to historical real estate bargains, the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 gets most of the attention. But Phoenix’s deal for the land that became South Mountain Park and Preserve deserves mention, too. In 1924, the city bought the park’s initial 13,000 acres from the federal government for $17,000. In today’s economy, that’s the equivalent of $300,000 — roughly what Arizona Diamondbacks star Ketel Marte earns

during a weekend series at nearby Chase Field.

The savvy purchase is still paying off a century later at one of the country’s largest municipally owned parks, which gives urban dwellers easy access to a relatively unspoiled Sonoran Desert landscape. “To be able to be away from the city, and experience what it would have been like to live here several hundred years ago, is just amazing,” says Jarod Rogers, deputy director for Phoenix’s Parks and Recreation Department. “Not many cities can boast that.”

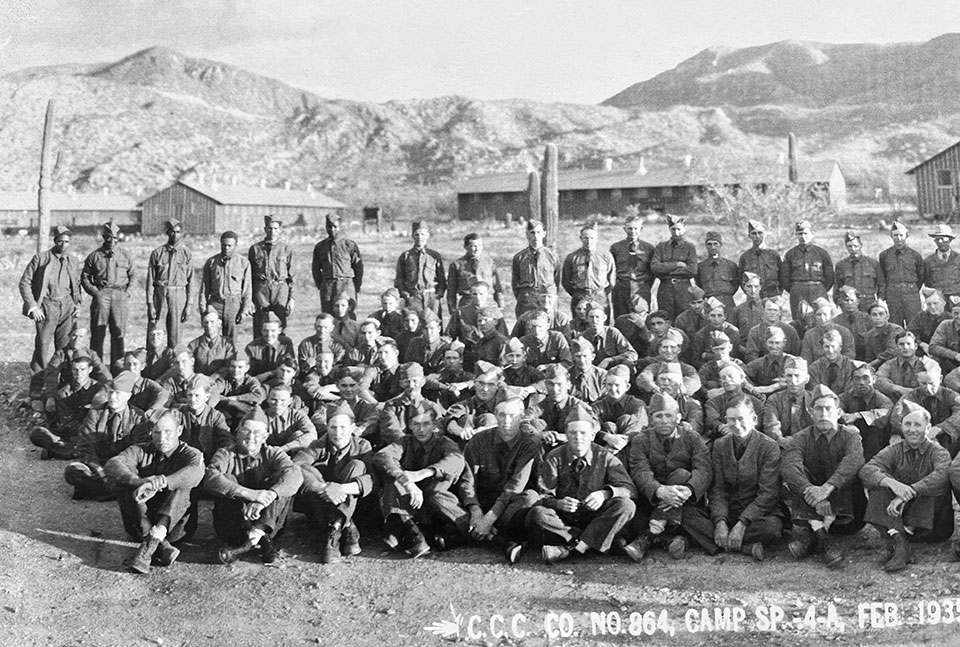

Things could have gone in a different direction at South Mountain, which the U.S. government once considered making a national park. Later, the federal Civilian Conservation Corps, which operated two camps at the site in the 1930s and ’40s, constructed much of the new city park’s infrastructure. The CCC’s work included hiking trails, the road to the top of the mountain and the stone structure at heavily visited Dobbins Lookout, which overlooks the Valley of the Sun.

“The work of CCC enrollees at South Mountain Park … was varied and vigorous,” Arizona State University student Michael I. Smith wrote in a 1994 study. “Rock for some projects was excavated and hauled from as far away as North Mountain, just below Thunderbird Road, and this assignment was given to the strongest enrollees in the camp.” The workers also planned to excavate a 500-foot tunnel linking Telegraph Pass to a road on the south side of the park, but that project never materialized.

Reminders of the more distant past, however, are all over. There are thousands of Hohokam petroglyphs among the park’s three mountain ranges (Ma Ha Tauk, Gila and Guadalupe), and the city acknowledges that the O’odham and Piipaash peoples have inhabited the landscape since “time immemorial.” More recent artifacts include a stone inscription purportedly carved by Spanish missionary Marcos de Niza in the 1500s, although modern historians say the inscription likely was forged sometime in the early 20th century.

Over the decades, park visitation has steadily increased as the Phoenix area has grown. In both 2022 and 2023, around 850,000 people visited for hiking, bicycling, horseback riding or other recreation. The recently completed South Mountain Freeway stretch of State Route 202 (Loop 202) lopped off a small portion of the preserve, but South Mountain Park now covers nearly 17,000 acres and offers more than 100 miles of trails.

This year, the park is marking its centennial with the reopening of the South Mountain Environmental Education Center, just off the main entrance road, sometime in the fall. The facility closed in June so its exhibit space could be renovated. “We’re trying to ‘future-proof’ the exhibits,” Rogers says. “Everything [previously] was more analog, but now, there will be more digital media for people to enjoy, and that allows us to load new media as our understanding of the park and the place changes.” South Mountain also hosts regular ranger-led programs and annual events; these include the National Trail Trek, a hike on the 15.5-mile trail that runs the length of the park, every January.

Rogers, a Valley native, says he learned to love the Sonoran Desert from hiking at South Mountain, and he credits his career as a landscape architect to his experiences among the saguaros, chollas and other desert life forms there. “I’m impressed with anything that can survive and thrive in this climate,” he says.

Part of the appeal, too, is getting those experiences right in Phoenix’s backyard. “You can be in a very urban environment and, in a few minutes, drive yourself to a trailhead, hike a little bit away on a trail and remove yourself from the city,” Rogers says. “I just think that’s amazing, and we want more people in Phoenix and beyond to be able to enjoy the park and appreciate it for what it is.”

To make that even easier, South Mountain Park is free to visit. Bargains don’t get much better.

PHOENIX South Mountain Park and Preserve, 602-262-7393 (ranger office), phoenix.gov/parks/trails/locations/south-mountain