Sedona’s newest park honors the city’s history, and one of the city’s oldest buildings is its focus. But just beyond the borders of Ranger Station Park on Brewer Road stands a reminder of a lesser-known chapter.

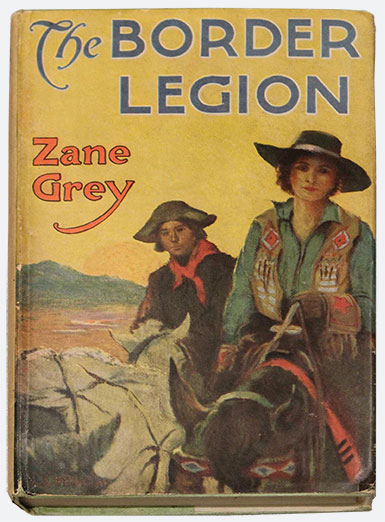

The stone house at the park’s southeast corner, in what now is Los Abrigados Resort and Spa, once was part of She-Kay-Ah Ranch and home to Lillian Wilhelm Smith. If you’ve heard of her, you’re in the minority. But most likely, you’ve heard of her friends. A longtime collaborator with Zane Grey, she illustrated many of his novels, including The Call of the Canyon, which brought Hollywood to Red Rock Country. And surrealist Max Ernst painted some of his most famous work at her guest ranch.

Though not much remembered today, during her lifetime, Wilhelm Smith made an impression on everyone who knew her. One relative recalled that she could become so focused on her work that she wouldn’t bathe or eat, and her brother-in-law called her the craziest woman he’d ever known.

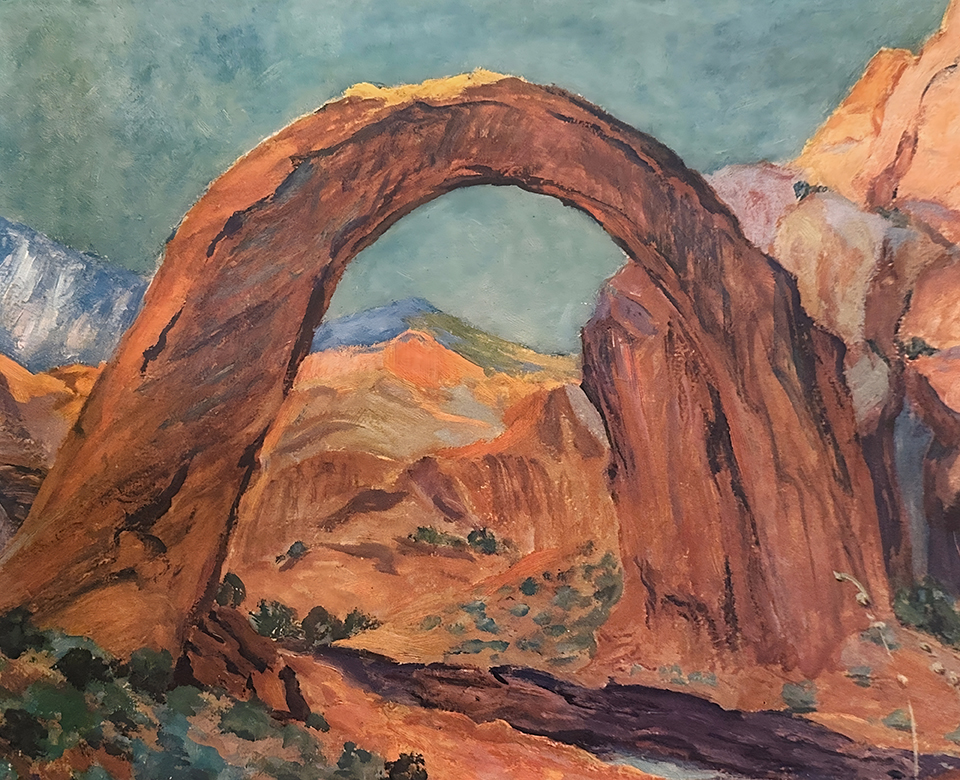

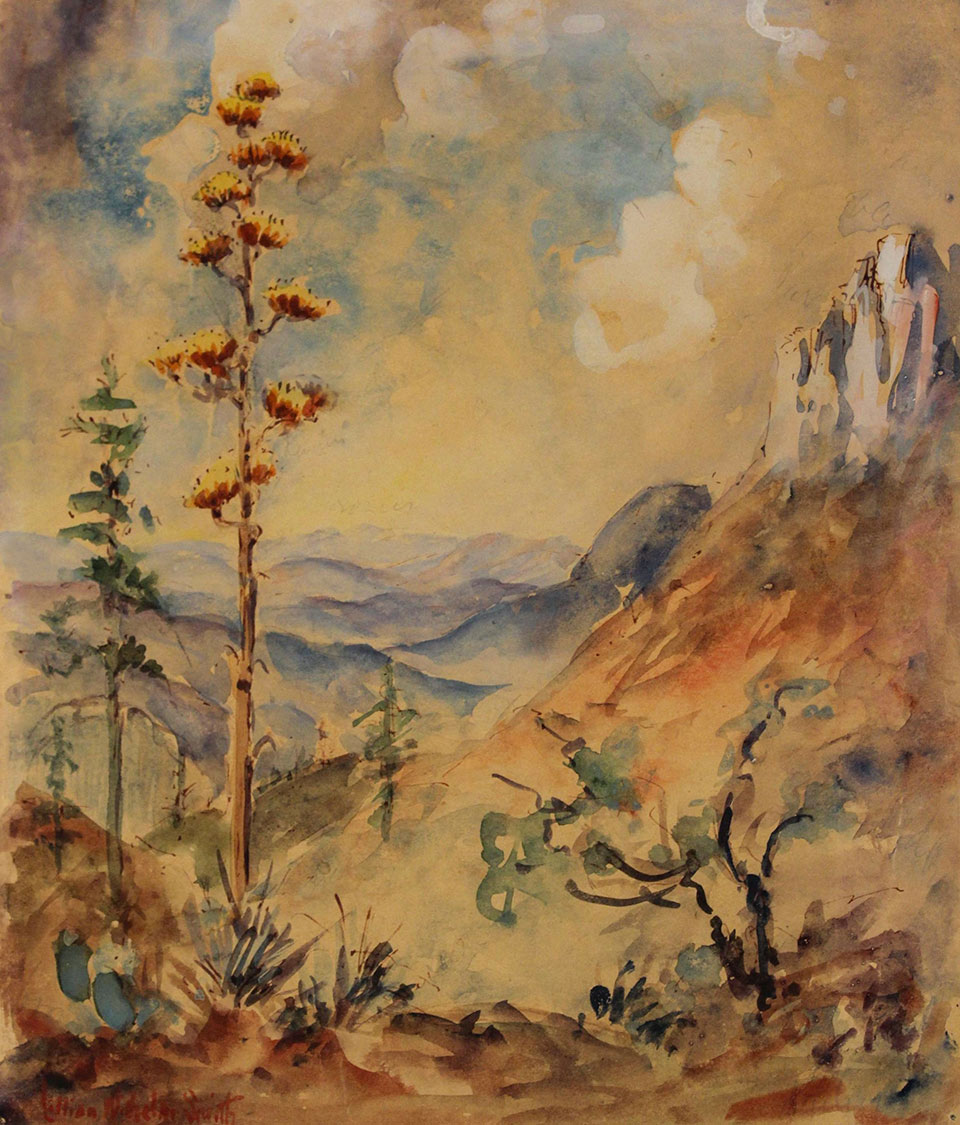

An intrepid traveler and lifelong friend of pioneers John and Louisa Wetherill, Wilhelm Smith may have painted Arizona more extensively than any other artist. She’s said to have been the first to paint Rainbow Bridge, just across the Utah state line, and Havasu Falls, and she eventually portrayed every major mountain range and canyon in the state. Her Indigenous-inspired china has been called the first regional mass-produced American dinnerware. And her tableware and paintings were exhibited all over the country.

Yet, after a career that spanned seven decades, Wilhelm Smith died in poverty, never having achieved the fame or success of her contemporaries.

Born in New York City in 1882, Lillian Wilhelm had a lineage that included philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and her great-uncle was an artist with a painting in a German museum. Her father’s Broadway store, which sold imported tableware, was successful enough to support a three-story Manhattan brownstone staffed with cooks, maids, a seamstress and a governess.

When Wilhelm was 10, her father thought her drawings promising enough that he hired a private art tutor. She enrolled at age 12 in the Art Students League and later at the National Academy of Design. But when the family’s fortunes declined, they had to move to more modest accommodations. Wilhelm’s mother’s health issues increasingly left Wilhelm to care for the household and her six younger siblings.

“I am wretched,” she complained to her diary. “[I] ache to get my pencils but am bound by the little creatures on my lap.” She was, she wrote, “burning to shake off all the trammels of conventionality and stand — alone — free and for Art!”

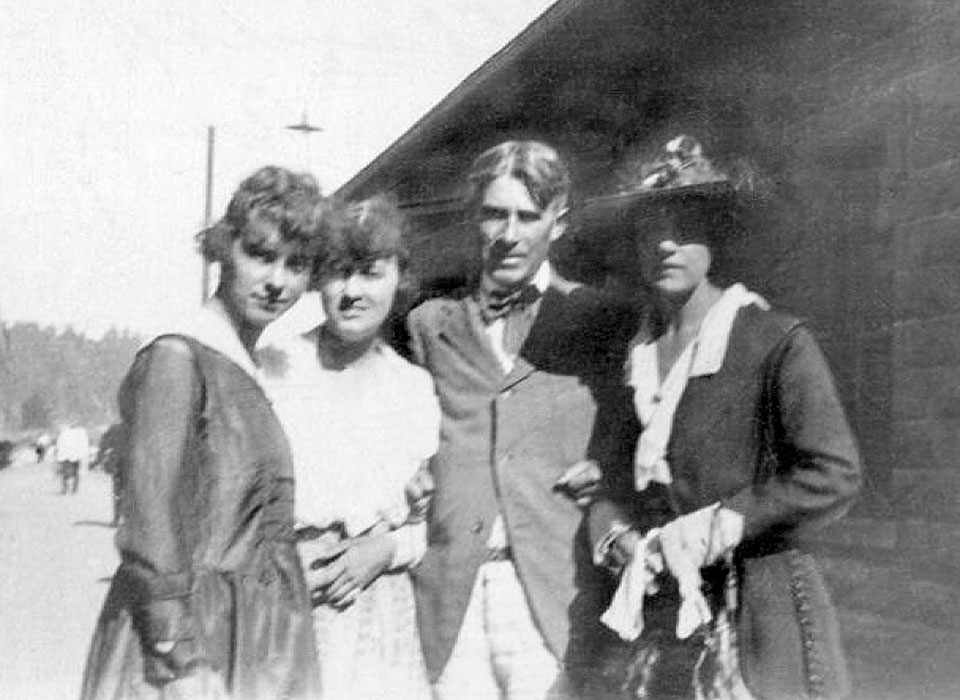

In 1905, Wilhelm’s cousin Lina Roth, better known as Dolly, married a handsome dentist with literary ambitions and helped finance his first novel, Betty Zane. It changed Zane Grey’s life. And Grey would change Wilhelm’s. Two years after marrying her cousin, Grey took Wilhelm to see “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s Wild West show at Madison Square Garden, where she got permission to sketch the Sioux and Arapaho performers. That first exposure to the West left her fascinated.

After the success of Riders of the Purple Sage, Grey had an idea for a sequel, and in 1913, he hired John Wetherill to take him to a sacred natural bridge he’d heard about, in Southern Utah’s Navajo Country. He invited Wilhelm to join him to paint the book’s illustrations.

“I was initiated into my life in this blessed land by a 400-mile horseback trip,” she recalled years later. “Only one automobile had ventured into the first hundred miles of those sandy wastes, and every sandstorm obliterated what roads there were. Our dear old guide … who showed me how to ride like a cowboy so that the long 25 and 30 miles that constituted the day’s loping and trotting would not too greatly tire me, showed me to a place at the end of the day where I could paint … and oh how I tried — sometimes to the point of tears — to interpret the divine beauty of those sunsets.”

Wilhelm was 31, five years younger than Louisa Wetherill, when the two rode into Kayenta to resupply at the Wetherill Trading Post for the last leg of their journey. Louisa thought Wilhelm eccentric, but their friendship would last for the rest of their lives.

Grey’s party endured quicksand and blistering heat riding through what the U.S. Geological Survey called “the most inaccessible, least known and roughest part of the Navajo Reservation.” Wetherill had been among the first non-Natives to see Rainbow Bridge, just four years earlier; a veteran archaeologist on that expedition had called it the most trying he’d ever experienced.

Arriving, finally, at their destination, Grey pronounced the arch “glorious” and added, “It absolutely silenced me.” For the next 10 days, Wilhelm “painted like mad,” producing the cover and illustrations for The Rainbow Trail. Grey used the setting for a number of novels, and he and Wilhelm would return again and again. Ultimately, their collaboration spanned 15 years and included trips throughout the Southwest and to the Galapagos Islands.

Before that, though, Wilhelm headed back to New York. “The beauty of Arizona … made me feel how necessary it was to continue my studies,” she said years later. Like Georgia O’Keeffe, she studied with Arthur Wesley Dow — who, like Wilhelm, had to rethink his color theories after visiting the West. “But in summertime the Navajo Reservation lured me,” she said. “By 1917 … a month away from Arizona seemed wasted.”

Wilhelm lived on Phoenix’s Camelback Mountain for her first four years in Arizona, a time that included marrying Westbrook Robertson in November 1917. He left nine months after Wilhelm bought a citrus ranch in Scottsdale, telling a neighbor he resented having married a poor woman who expected him to “squat on 20 acres.”

In 1923, Wilhelm joined Grey on another trip to Rainbow Bridge with pioneering filmmaker Jesse L. Lasky. She later said she and a wrangler named Jesse Smith spent 27 days in the saddle while scouting locations for The Vanishing American, an adaptation of Grey’s book of the same name. She soon filed for divorce from Robertson, and to everyone’s surprise, she married Jesse as soon as it was granted, in May 1924.

“He was the husband every woman longs for,” one female acquaintance said. “He took care of her,” including by piling up rocks to make a tub when they were camping so she could take a bath. Always on the lookout for interesting landscapes, Jesse took his wife to isolated painting locations, including a fire tower in the Bradshaw Mountains and a remote spot at the Grand Canyon.

“I learned from members of the geodetic survey that no other white woman has ever been known to go within 20 miles of my spot on the rim,” she recalled of the latter site. “Four or five days later, Jess carried the [3-by-5-foot] canvas on the toe of his boot … along that rough terrain (there was no trail) the 20 miles to where our [Studebaker] was parked. … What an effort that was.”

Early in their marriage, the Smiths owned a partnership in a Tuba City trading post and guest ranch they called She-Kay-Ah, “my home” in Diné. When the partnership dissolved, they traveled the state on roads described as poor, bad and wretched. In 1929, Wilhelm Smith descended to Havasu Canyon’s remote village of Supai, becoming perhaps the first Anglo woman to paint the famous waterfalls in the home of the Havasupai people.

At the 1928 Arizona State Fair, Wilhelm Smith introduced a line of tableware in two patterns inspired by Navajo and Apache designs. Included in traveling exhibitions around the country, it was recognized at a national show as “the first authentic effort to bring archaeological beauty into line with utility.” Goldwater’s department store later sold her Hopi-inspired line.

As the economy sank into the Great Depression, Jesse took a job with the Prescott National Forest, while Wilhelm Smith worked as artist in residence at the Arizona Biltmore’s art shop in Phoenix, filling it with her paintings and tableware. She also collaborated with Lou Ella Archer on two books that combined her paintings with Archer’s poems. Arizona Highways featured a selection in two 1939 issues.

In 1937, Wilhelm Smith sold the citrus grove and she and Jesse opened a second She-Kay-Ah Ranch in Sedona, leasing land that once belonged to T.C. and Sedona Schnebly from George Black. Jesse built a few detached cabins, while Wilhelm Smith hired a local cook and improved the fields and orchards to provide fresh produce. It was hard work, but she told visitors she’d never had less or been happier.

In 1946, a pair of struggling artists named Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning spent a summer at She-Kay-Ah. “The ranch lay in a marvelous spot on the bank of a creek,” Ernst wrote in his biographical notes, remarking on the locals’ “unobtrusive kindness and wholly natural hospitality.” While there, Ernst painted Vox Angelica, which he considered among the top five paintings of his career, according to art historian Mark Rownd, who owns the house Ernst built nearby on Brewer Road.

That September, filmmakers arrived at She-Kay-Ah to shoot Gunfighters, based on Grey’s novel Twin Sombreros; the character Brazos Kane is thought to have been modeled on Jesse. By then, Sedona was changing. Beginning with 1923’s The Call of the Canyon, Hollywood had brought an influx of people, and in the 1930s, the state built new highways through town. Electricity and tourists arrived after World War II, and the land She-Kay-Ah occupied became valuable. In 1947, after Black died, the Smiths lost the ranch to his widow.

“I think [the Smiths had] an owner-financed handshake deal with George Black,” Rownd says. “From different sources I’ve read, his widow denied they had an agreement, and [the Smiths] didn’t have a good lawyer.”

They never recovered from the loss, and their already tenuous finances began a slow decline along with Jesse’s health. When he was admitted to the veterans hospital in Prescott, Wilhelm Smith rented a tiny house nearby. Jesse died in 1960, at age 73; in gratitude for his care, his widow donated a painting of Rainbow Bridge to the hospital.

After Jesse’s death, Wilhelm Smith’s health and mental faculties deteriorated. The Wetherills’ granddaughters Johni Lou and Dorothy Lillian, the latter named for Wilhelm Smith, lived in Prescott and did what they could.

“I liked her,” says Johni’s daughter, Kim Lavoie. “She was really an elite lady … very proper. And then, as I got older, she went downhill. … My mom would pick her up, my sister would clean her house, and then she would bring her back. That’s the only way she’d let her in the house to clean. …

“As she got older, she was funny. She accused my mom of stealing her girdle. I asked my mom, ‘Why did you take her girdle?’ She laughed and said, ‘Oh, no, her mind is failing, is all.’ ”

Wilhelm Smith moved to the Arizona Pioneers’ Home in her mid-80s and died there in 1971, just short of her 89th birthday. Her ashes were placed in Jesse’s grave.

“She was definitely one in a million,” Lavoie says. “She had a lot of personality — somebody who could captivate your attention.” Pausing, she chuckles. “I wonder where her girdles are.”