ADA BASS

1867-1951

Ada Diefendorf Bass, a classically trained pianist born in New York in 1867, didn’t choose to be the first Anglo woman to raise a family at the Grand Canyon. But when she was in her mid-20s and unmarried, a visit to her aunt in Prescott seemed appropriate. Single men were abundant in the Arizona Territory.

On a tour, she fell in love with her guide. William Wallace Bass — W.W., as he was known — had arrived at the Canyon 10 years earlier, after doctors had prescribed fresh air and physical work to cure a nervous breakdown. A self-taught geologist, W.W. wrote poetry and played the violin.

Ada went home, packed her things and returned to Arizona on the last day of 1894. “Attended New Year’s ball in Prescott,” she noted in her diary January 1, 1895. On January 4, she wrote, “Left Prescott for Williams with W.W. ... W.W. went to Flagstaff to get license.” On the 6th, “Married at M.E. Parsonage 7:30 p.m. by Rev. McFadden. Were serenaded by band and nearly drove crazy.” A shivaree wouldn’t have been music to a musician’s ears, but it was a reasonable foretaste of things to come.

Leaving Williams in W.W.’s four-horse-drawn stage, the newlyweds carried a month’s worth of provisions, a paying guest and a man hired to tend the horses. Ada looked forward to a taste of camping. As a storm flooded a normally dry creek bed, she struggled to save the provisions from seeping water while the men dealt with the stage and horses. Arriving late at a camp W.W. called the Caves, they built a fire, dried bedding, made coffee and went to bed. Stranded for days by the storm, Ada wrote, “Slept in a tent and ate down in the ‘Cave,’ going back and forth on a rough ladder.” Reaching the Canyon in a snowstorm on February 10, she wrote, “Fixed up the camp and tried to keep warm.” Might we call this a honeymoon?

Moves were constant — from Bass Camp, to the Caves, to Ash Fork or Williams. Ada stayed in town when W.W. was away working his mines. When out of money, she slept in their stage, washed dishes for meals or occasionally played piano for a dance.

At Bass Camp or the Caves, there were continually tourists for whom Ada cooked, made beds and did laundry. If cisterns ran dry, doing laundry meant a three-day trip to the river — wash, dry, return. Her diary entry for this is a lesson in restraint. “Did laundry,” she wrote. By the time Ada was a few months pregnant, life at the Canyon felt old. As her first wedding anniversary approached, she wrote, “Thus endeth this horrible year; can the next be worse?”

When W.W. fell ill after searching for horses in a snowstorm, his illness used up their money. “Old Cervis, the only store in town, don’t like to trust us for groceries,” she wrote in April. “God help us.” To pay rent in town as W.W. recovered, Ada sold her good bed linens; she then sold her silverware and music book to buy food.

May 1896: “Began packing my trunk to beat it, back to home and mother,” Ada wrote. She stayed away for three years, although ultimately, W.W. charmed her back. When the railroad arrived at Grand Canyon Village in 1901, W.W. built a house to provide overnight stops for guests. Later, he built a two-story house nearer the village. Ada, happier, could see friends easily and work less since, by then, most tourists came for day trips. In 1927, after selling their Grand Canyon holdings to the Santa Fe Railway, Ada and W.W. moved to Wickenburg.

Blanche Kolb

1883-1960

An erstwhile Harvey Girl, Blanche was elegant, gracious and — after her marriage to Emery, the younger Kolb brother — ready for life on the rim. She moved into the house Emery and brother Ellsworth constructed in 1905 to serve as home and studio. Like Ada’s house, it had no electricity or running water, although, if the cisterns were empty, 4.5 miles to Indian Garden, and water, was easier than Ada’s 8-mile ride to the river.

While the Kolb brothers were occupied with photographing tourists riding mules down Bright Angel Trail, Blanche took care of their retail shop; managed the finances and household; cared for their daughter, Edith; and, for years, hosted social events to smooth over Emery’s often-difficult relations with all the entities that wanted him out of business.

Polly Mead Patraw

1904-2001

Polly Mead was a botany student at the University of Chicago in 1927 when she first saw the Grand Canyon, the last stop on a professor-led summer field trip to several national parks. The group set up camp on the Canyon’s rim. When Polly wondered why something as big as the Canyon wasn’t visible, her professor suggested a short path to an overlook. And, like everyone on a first look, Polly was overcome by the Canyon’s power.

She later spent two summers doing a study of plant life on the Kaibab National Forest for her master’s thesis — a work that provided a basis for further studies on the North Rim. Because her adviser insisted that her research contain information about the region’s geology, Polly hiked from the North Rim to the South Rim to meet a naturalist with a specialty in geology.

Wanting to work at the Canyon after graduation, she applied to the U.S. Forest Service. No jobs for women, she was told. But the National Park Service hired her as a ranger-naturalist, making her the first woman to hold that position in the Grand Canyon and the second to do so in the Park Service. She was sworn in by Assistant Superintendent Preston Patraw, her future husband, in August 1930.

ELZADA CLOVER & LOIS JOTTER

1897-1980 & 1914-2013

In 1938, botanist Elzada Clover and graduate student Lois Jotter became the first two women to run the entire Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. On their 666-mile trip, they made a survey of plant life that remains the only comprehensive study of the riparian ecosystem before Glen Canyon Dam irretrievably altered the Canyon’s landscape.

Elzada considered reaching the river by mule, but she changed her mind after talking with Norman Nevills, a pioneer of commercial river running. Nevills built three boats for the expedition, which began at Green River, Utah.

“Women have their place in the world, but they do not belong in the Canyon of the Colorado,” Buzz Holmstrom, the first person to solo the Colorado through the Grand Canyon, declared to the world — hardly an isolated male thought at a time when women were rarely acknowledged for who they were. (Elzada had earned her Ph.D. in 1935 but wouldn’t make full professor until 1960.)

Lois had her own opinion. “Just because the only other woman who ever attempted this trip was drowned is no reason women have any more to fear than men,” she said. She was referring to Bessie Hyde, a newlywed thought to have drowned on her honeymoon with her husband, Glen, who considered life jackets unnecessary.

As the Nevills-Clover Expedition moved downriver, the scientists, being women, were expected to cook. They got time off when, after camping one night on the beach near Bright Angel Trail, they hiked it to the top. Blanche Kolb met them with iced tea and invited them to lunch. The following day, Elzada and Lois were thronged by autograph seekers in Grand Canyon Village. I can imagine their relief, and even a sense of the normal, as they hiked back to the river the next evening.

On July 30, 43 days from the journey’s beginning, the group reached Lake Mead, although they were still 80 miles from docking at Boulder Dam. Rising at 4 a.m. the next day, they rowed for four hours, then pulled into a side canyon to eat and nap. At that moment, Holmstrom turned up in a powerboat to tow the three boats to dock. On his own Canyon run, a passing powerboat on the lake had refused him a tow. I guess he changed his mind about who belonged on the river.

Georgie White

1911-1992

Georgie White and her 15-year-old daughter, Sommona Rose, were bicycling toward Santa Barbara on California’s U.S. Route 101 when Sommona Rose was hit and killed by a drunken driver. Seeking some measure of solace for Georgie, friends took her to a Sierra Club meeting. There, she met Harry Aleson, who was scheduled to lead a club hike from Quartermaster Canyon, a side canyon on Hualapai Tribe land, to Mount Dellenbaugh. Georgie signed on to the trip. They didn’t summit, but they formed a friendship, often hiking together.

But Georgie wanted more than hiking trails to deal — to the extent that one can deal — with her loss. She wanted the river. That neither she nor Aleson could afford a boat was, for Georgie, irrelevant. Combining swimming with using their life jackets on the lower river, they were guaranteed an intimacy with the river that few people initiate on purpose. After a 20-mile hike from Peach Springs to their put-in, their float to Lake Mead provided some worrying (but educational) moments.

A longer trip the following summer started with a makeshift raft that lasted a few hours. Continuing, they alternated use of a one-person air float designed for rescue at sea. Upon reaching Lake Mead, Aleson swore off such trips, but Georgie used her experience as an education she felt would have required years any other way. In her book Grand Canyon Women, Betty Leavengood quotes Georgie: “I came to understand how the currents acted both on and below the surface. I saw firsthand how rocks affect the water, and I learned some important lessons about controlling myself in high water.”

After a few summers alone on the river, experimenting with her 10-person U.S. Army surplus raft, Georgie took her first passenger in 1952, on a float with enough upsets to give her confidence that she could manage. In 1953, she lashed three surplus rafts together, mounted an outboard motor to the stern and launched Georgie’s Royal River Rats, which she owned and ran for the next 45 years. She developed a reputation for flouting a few rules, but she also inspired the confidence she herself felt.

Aleson thought women should not be guiding on the Colorado. But Georgie — the first woman to guide, and a pioneer in using rafts that became the accepted mode of river travel — is part of Colorado River history. In 2001, Georgie Rapid was named for her.

Katie Lee

1919-2017

An Arizonan by birth, Katie Lee tried a stint in Hollywood in the 1940s, with modest success, but by the 1950s, she’d fully developed her talent as a singer-songwriter. Returning to Arizona to perform in 1953, she watched a film featuring high school friend Tad Nichols making his first powerboat run through the Grand Canyon. Her reaction: She had to get there. But she had no money. Nichols suggested she bring her guitar and enough money for food, and they’d make something work.

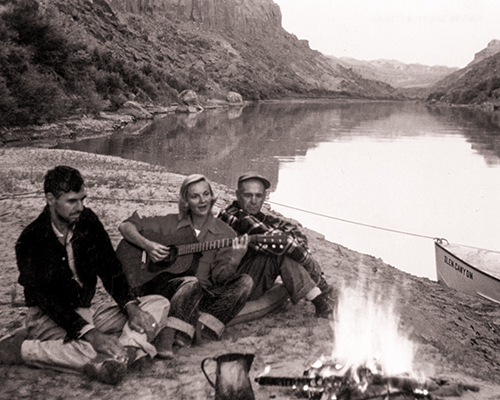

Playing and singing in camp is a reasonable way to hitch a ride on a raft. And Katie’s voice was like the river itself: a flow and a wildness that could make even someone who hates water long for the river. That 1953 trip through the Canyon marked the beginning of a long career running rivers — and a lifetime of environmentalism.

The Grand Canyon led her to Glen Canyon. Carved by a 170-mile length of the Colorado, and part of the immense system of Colorado-carved canyons, Glen Canyon now lies under Lake Powell. In the mid-’50s, Katie made three trips through the canyon with Nichols and Frank Wright. The last trip included photographer Martin Koehler, whose photographs are in a collection in Katie’s name at Northern Arizona University’s Cline Library in Flagstaff.

The group cleaned canyon walls of graffiti. They documented locations of Indigenous peoples’ sites and artifacts. When a plan to construct nine reservoirs on the Colorado and its main tributaries was approved, Katie wrote protest letters to government officials, composed and performed protest songs, and joined the Sierra Club and the Glen Canyon Institute. After Glen Canyon Dam was built, she continued working with activists such as David Brower and Edward Abbey to attempt to remove it — she even said she would blow it up, if she only knew how — and to prevent such projects in the Grand Canyon and on other rivers.