Editor’s Note: When I was discussing this month’s portfolio with Photo Editor Jeff Kida, I asked, “What can we do that’s different?” About 10 minutes later, he walked into the art department with a handful of black-and-white prints — he’d been in the vault. What he found is what you’re about to see.

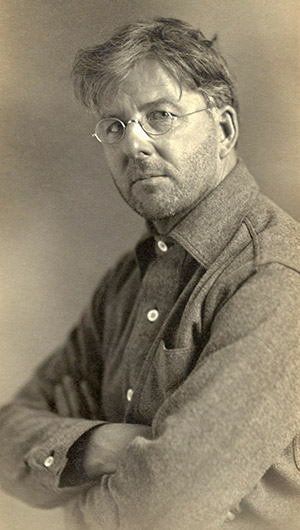

For Roland Reed, making photographs of the country’s indigenous people was as much a calling as it was a passion. Born to a farmer and a homemaker outside of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, in 1864, Reed was fascinated by stories of the tribes near his childhood home, particularly the Menominees and their legendary leader, Thundercloud.

But it wasn’t until Reed left home at age 18 — traveling first to Minnesota and Canada, then through the Plains states, as part of his work for the Canadian Pacific and Great Northern railways — that he began to explore how deep his interests ran. A few years later, he left his job and set out on a solo expedition to learn about and document as many tribes as possible.

As he traveled, Reed supported himself by selling small portraits, including some of Arizona’s Hopi and Navajo people, which he made with wax pencils. He also taught others to sketch.

By 1893, though, Reed had become an apprentice to Montana-based photographer Daniel Dutro. Together, the two provided countless photographs of Native Americans to the Great Northern Railway’s news department. Although many of the details about Reed’s time in the American Southwest have been lost to history, it’s believed he spent several months in and around Canyon de Chelly in 1913. There, some of the photographs in this portfolio were made.

Reed’s philosophy about photographing Native Americans was made clear in one of his personal letters, as quoted in the November 1980 issue of Arizona Highways: “In approaching the Indian for the purpose of taking his picture, it is necessary to respect his stoicism and reticence, which have so often been the despair of the amateur photographer.”

Indeed, Reed — who became known later as one of the 20th century’s great pictorialists, for the use of light and the sense of impressionism in his portraits — wouldn’t ask outright to make a photograph. “I never suggest the object of my visit,” he wrote. “When the Indians, out of curiosity at last, inquire about my work, I reply casually, ‘Oh, when I’m at home, I’m a picture making man.’ ”

Inevitably, his subject would request his or her portrait, and Reed would capture a look, a movement, a moment in time.

After returning to the Midwest, Reed opened a small studio and compiled a catalog of 48 of his images of Native Americans for sale. Sadly, the photographer saw little fame or fortune from his work.

Perhaps more tragically still, in 1934, Reed died in Colorado Springs, Colorado, after a freak accident. According to biographer Ernest Lawrence, Reed slipped on a banana peel, breaking several vertebrae. He developed inflammation of his spinal cord and ultimately died of double pneumonia. He’s buried in Colorado, in a grave that faces Cheyenne Mountain, once the source of spiritual inspiration for the Cheyenne and Arapaho people.

Although Reed’s story is only occasionally told, Eugene S. Bruce, one of Reed’s contemporaries and a photography critic, did not mince words when it came to the impact of Reed’s work: “As mere works of art, these pictures have a value seldom found in photographs, but as pictorial evidences, as historical illustrations of an epoch that is almost closed, the pictures in this collection should be preserved and treasured.”

— Kelly Vaughn