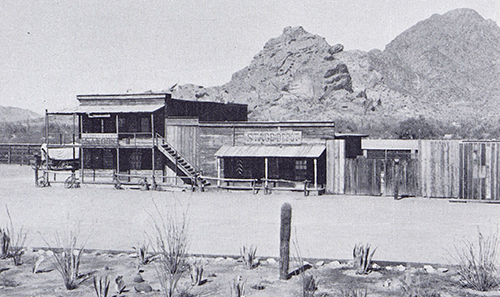

Ask an Arizonan about the state’s filmmaking history, and you’re likely to hear about Old Tucson or Apacheland. But Phoenix once had a movie studio, too. It was best known for the television series 26 Men, but episodes of popular TV shows such as Wanted Dead or Alive, Have Gun — Will Travel, The Rifleman and Gunsmoke were also produced there, as were a number of feature films.

Originally called Valley of the Sun Studio, the enterprise became better known as Cudia City, after its charismatic founder, Salvatore Pace Bundanza Cudia. And some have made the case that it inspired the development of the state’s more iconic movie sets.

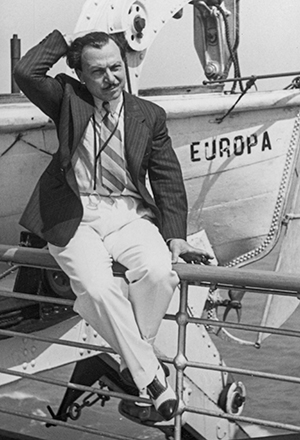

Born in Sicily, Cudia came to Arizona in the late 1930s. By then, he had organized an Italian opera company in Washington, D.C., worked at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City, owned and operated a Long Island hotel, gained a reputation as a portrait painter and sculptor, and spent years in the film industry, with soundstages in Florida and California.

But before he came to America at age 17, Cudia had studied for the priesthood. “The story is that back in the homeland, families would typically identify somebody to go into the priesthood,” says Cudia’s great-grandson Jim Judge, the family historian. Cudia received a tremendous Jesuit education, Judge says, but he was flamboyant and had no desire for a solitary life. “I guess the cleanest break he could make was to immigrate to America,” Judge says.

Long a fan of silent movies, Cudia became interested in the film industry while engaged in the photographic study of an automobile assembly line for Henry Ford. Intending to make silent movies, he built a soundstage in Florida, but frequent rain limited the number of filming days. More importantly, silent movies were on their way out. “Timing was always an issue for him,” Judge says.

After leaving Florida, Cudia built a soundstage in California. Fluent in several languages, he made Polish-language Westerns that did well overseas. But clear skies, natural scenery and inexpensive land brought him to Arizona. R.C. Stanford needed cash at the time, and Cudia seized the opportunity to buy the former governor’s land at 40th Street and Camelback Road — miles outside of town in those days — at a very good price.

There, Cudia built an air-conditioned, soundproof studio and a movie set. He made plans for a dozen films using Cudiacolor, a process he patented. He hadn’t been in Arizona long before Columbia Pictures came calling. The Hollywood studio was looking for a place to film a movie starring William Holden. An existing sound studio and movie set made Cudia City an attractive option, but the parties never came to an agreement. Columbia instead built a movie set near Tucson to shoot the 1940 film Arizona. That set would ultimately become Old Tucson Studios.

Cudia City had released only a handful of films when World War II interrupted Cudia’s plans. A World War I veteran, Cudia again served his adopted homeland by producing patriotic promotional plaques for the federal government. He also opened his soundstage to civic groups and service members.

After the war, Tucson Raiders was the first of several Red Ryder movies produced at Cudia City, marking Wild Bill Elliott’s debut as the iconic character. A stream of movies and TV shows followed. 26 Men, based on the Arizona Rangers, began filming at Cudia City in 1957 and soon became the No. 1 syndicated TV Western.

Horse trainer, actor and stuntman Don Paulson came to Arizona with Steve McQueen, who was starring in Wanted Dead or Alive. Paulson worked on that show as well as 26 Men and Have Gun — Will Travel.

“[Paulson] was part Native American, so he played a lot of Native American parts,” says the late actor’s son, Ted Shred. “On one episode, I think of 26 Men, he played a general. At the end, he was out looking for an Indian that was missing. He [also played] the Indian earlier in the episode, so he was looking for himself. People used to laugh about that, but that’s how they made movies back then.”

Stunt doubles used to dive or roll into sand or cardboard in those days, says Paulson’s daughter, Jeannie Flynn. The job didn’t pay well, and there were plenty of mishaps. Paulson almost died when he hit his head performing a stunt on Camelback Mountain. Another time, he had to run for cover when a shed blew up.

“Anytime he was hurt, [my mother] would tell him he needed to quit,” Flynn says.

DURING THE YEARS 26 Men was filming, Cudia City became Dino Castelli’s playground. Before he was old enough to go to school, his mother took a job as Cudia’s secretary and took him with her to work.

Cudia’s office was inside the Western movie set, on a little plaza, Castelli recalls, and Cudia Restaurant was just south of the office. Called the most fascinating restaurant in Phoenix by Good Housekeeping, it included an outdoor dining area that had a pool with a 30-foot waterfall. “It was really incredible,” Castelli says, adding that the restaurant was the place. “A lot of Hollywood people were always there,” he says.

Free to wander, Castelli knew to stay out of the way during filming. Ducking into the office one day as shooting for 26 Men was about to begin, he pushed aside the lacy window curtains to watch the action. When the episode aired, he saw himself peeking out. “It cracked me up,” he says.

Castelli remembers Cudia as strong, regal and a gentleman. Always well dressed in Western-style clothes, he smoked cigars and drove a big Cadillac. “Mr. Cudia was just a real interesting guy,” Castelli says. “He was an artist and an art collector. You would have expected him to be snotty, but he wasn’t. He was always really nice to me.”

Known for his generosity, Cudia allowed Castelli’s family to use the swimming pool when the restaurant was closed, and the family hosted birthday parties there. Judge remembers that after his sister Rayanna dazzled Cudia on his baby grand during a Christmastime visit, the family returned home to find a piano in their living room.

Cudia was generous with the community, too. Several churches got their start at Cudia City, and for a time, Cudia offered the soundstage and its equipment to a Scottsdale theater troupe for free. Later, the soundstage became a popular teen venue.

“He would hold dances — non-alcoholic — [and] bring in top talent from California,” Judge says.

AFTER WORLD WAR II, the population of Phoenix soared, and so did air traffic from Sky Harbor Airport. By the time 26 Men began filming, the city was encroaching on the studio, where scenes often had to be reshot because of car horns or airplanes.

On a particularly frustrating day, local stuntman and actor Victor Panek started thinking the Superstition Mountains might make a suitable alternative. He and his partners created Four Star Productions, which eventually resulted in Apacheland Movie Ranch. It opened around the time filming at Cudia City ended.

The facility continued to operate for a while as a restaurant and resort, but after a fire destroyed the buildings, Cudia sold off the land in the 1960s. A restaurant called The North Bank, now the location of Chelsea’s Kitchen, was built where the Western town stood. The land across 40th Street, just north of the Arizona Canal, became a singles-only apartment complex; it’s now Capri on Camelback. Cudia subdivided the land north of the movie set for a residential development that still bears his name.

He also built the bridge over the canal on 40th Street and donated it to the city. A bronze plaque on the northwest pillar memorializes Cudia City and acknowledges the donation. Judge has a newspaper clipping with a photo of his great-grandfather, with a cigar, watching the construction.

After devoting the last 10 years of his life to collecting art and developing Cudia City Estates, Cudia died in 1971, at age 83. His son, Edmond, raised by an aunt in New Orleans after his mother died, was his only heir. Edmond moved into Cudia’s home, which had been built in 1959, and invited his daughter, Carmelite Cudia-Judge, and her family to join him. She was struggling to raise six children, including Jim, after her husband became disabled. “My grandparents were very generous and benevolent to help us,” Judge says, “and put us in a much better situation.” Judge lived in the house with his mother until she died in 2016.

Cudia’s ashes remained unclaimed for more than 40 years. Judge says the family believed his body had been buried in a local cemetery until a veterans group contacted them. In 2013, the group interred Cudia’s ashes during a fitting ceremony at the National Memorial Cemetery of Arizona. Judge and his mother rode in the procession.