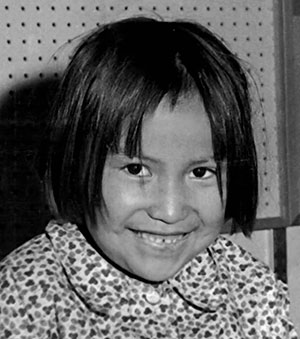

The only things my mother heard were the sounds of children’s cries, whimpers and soft footsteps as they fled into the night and she hid in fear beneath a thin, unfamiliar white blanket. Reduced to a silent observer, she was raised during the boarding school era, when her days began with making her bed and rigorous exercise, as if in preparation for military deployment. She ate breakfast from a cold tray alongside her fellow students. Her long brown hair was trimmed to a few inches, partly obscuring her face. Still, she maintained her smile.

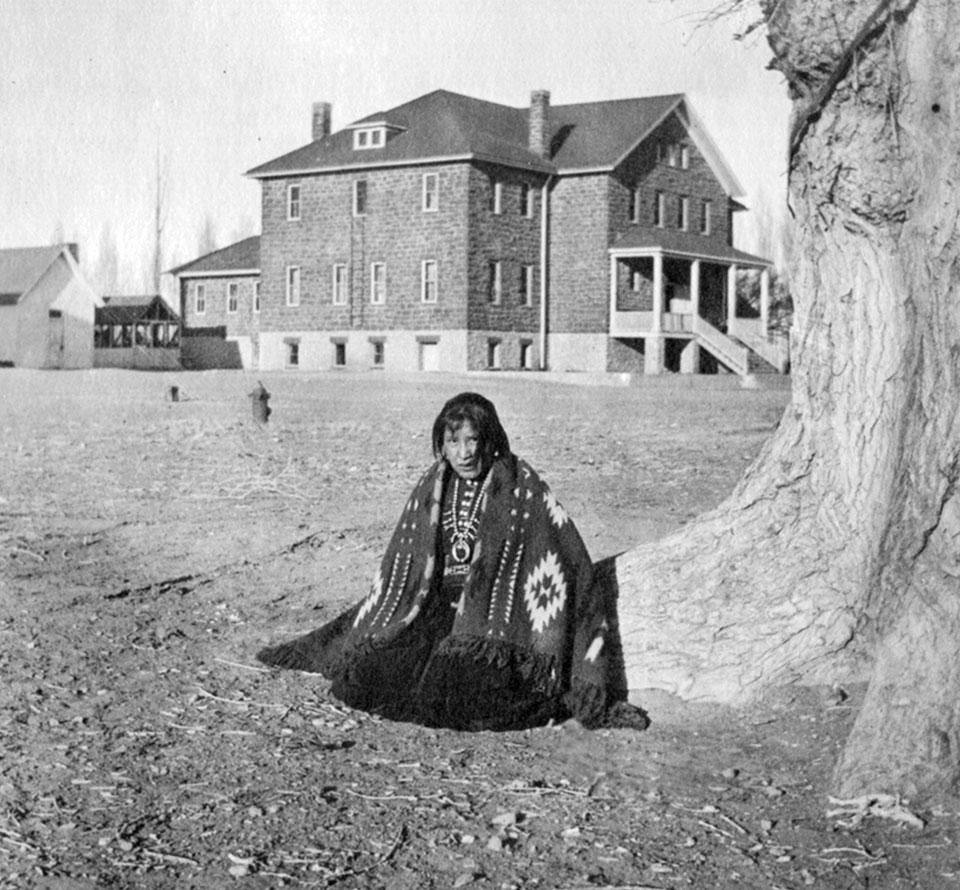

It was worse for my grandmother, who was forcibly taken from her home in Arizona by strange men and transported on horseback through the desert to the Intermountain Indian School in Brigham City, Utah. And for my grandmother’s sister, who returned home bearing a forearm tattoo inscribed with unfamiliar symbols that represented her assigned English name within the system. I am grateful for my mother, who endured and survived so I could be brought into this world with my brothers.

Our memory acts as a tribute to our family legacy and a story for the future that will safeguard our ancestral heritage and resilience. My mother, grandmother and many other relatives are just a small part of our community that was forced to adapt to Western society.

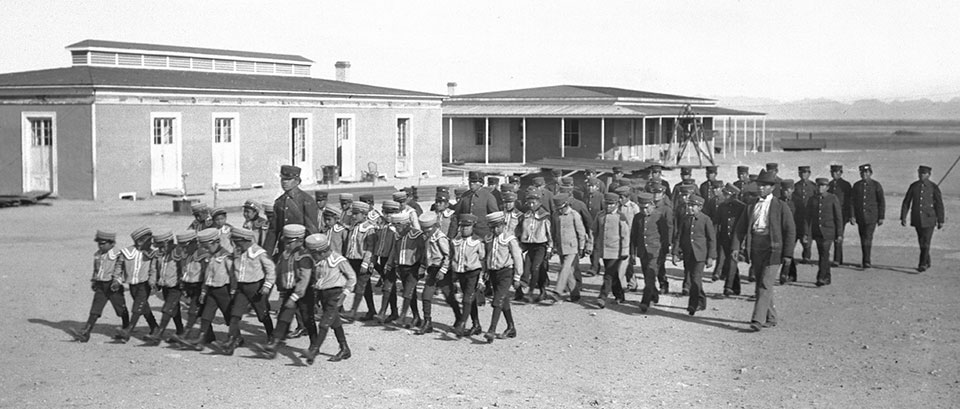

In 1900, there were 20,000 Indigenous children in boarding schools, according to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. By 1925, that number had more than tripled. Overall, from 1819 to the 1970s, the United States enacted policies that created and maintained Indian boarding schools throughout the country. These institutions aimed to culturally assimilate Native American, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian children by forcibly separating them from their families, communities, languages, religions and cultural practices. During their time at these boarding schools, many children like my grandmother and mother suffered physical and emotional abuse, and some lost their lives.

In June 2021, Secretary Deb Haaland and the U.S. Department of the Interior initiated efforts to confront the difficult history associated with federal Indian boarding school policies. Through the creation of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, the U.S. government aims to address the intergenerational effects of these policies and highlight the historical and ongoing trauma experienced by Indigenous communities. The initiative reports that 973 students lost their lives during the boarding school era; given the dark nature of this period in American history, the project stands out as one of the few documents that reveal the trauma of the era.

However, due to inconsistent federal reporting on child deaths — including their numbers, causes and burial sites — the accuracy of such figures remains uncertain. An investigative report by the initiative identified more than 50 marked or unmarked burial sites across the former boarding school system — underscoring the urgency of honoring the memories of those who suffered and providing a clearer understanding of the effect of these schools on Indigenous populations.

While many Indigenous families share a common history marked by extensive assimilation, the experiences of that era have led Indigenous people down vastly different life paths. I can see that in my recent matrilineal line, whose lives were profoundly altered by their time in boarding schools. They could have remained integral members of their Northern Arizona communities, deeply connected to their cultural heritage. Instead, they became wanderers.

My grandmother returned to Arizona years after her boarding school experience, but she was irrevocably changed and never fully regained her sense of self. My mother didn’t return at all and drifted even further from her cultural roots. While she is aware of her heritage, her connection to it has been severed, as evident in her limited cultural understanding and her reluctance to teach me the Navajo language. I think that stems in part from her experience of institutional violence and wanting to protect my siblings and me. As a result, I, too, have grown further away from my culture — not only geographically, but also culturally — because two generations of my family were separated from it.

Growing up, I always wondered what my life would have been like if boarding schools had never existed. Would I be full Diné? Or half, like I am now? Would I have grown up on the Navajo Nation and learned how to ride horses and play in the canyons, like my mom did growing up? Or would I be doing half as much as I am now?

While my grandmother and mother faced forceful evictions from their homes, I felt a desire to enroll in a different kind of boarding school as I approached high school. I wanted to attend Mt. Edgecumbe High School, which was nearly 700 miles away from our home in Fairbanks, Alaska, and reachable only by plane or boat. My family was among the few Indigenous families in Fairbanks, and I wanted to be surrounded by other Indigenous students and connect with my community — a challenge for many Indigenous people, given that only about 1 percent of the U.S. population identifies as American Indian or Alaska Native. Instead, I eventually enrolled at a public high school where I was the sole Native student in the classroom.

During my undergraduate years, I sought out people who resembled me, seeking a sense of refuge in what felt like an unending desert. There, too, I longed to be part of an Indigenous community, but again, I faced challenges: According to the Postsecondary National Policy Institute, only about 17 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives age 25 or older have earned a bachelor’s degree or higher, a rate significantly below the national average of 36 percent.

As a result, I often find myself explaining my identity, educating others or putting in extra effort to have my viewpoint acknowledged as valid. When I do encounter other Indigenous students in academic settings or elsewhere, I recognize the collective effort it took for us to reach this point in an environment that has not always been welcoming. We have navigated the challenges and traumas experienced by our parents and grandparents — and, perhaps, formed a bond as exiles from the boarding school era, connected by the threads of our shared history.

There were about 523 known Indian boarding schools in the United States, according to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. On a late-October day in 2024, survivors of some of those facilities fill a gymnasium on the Gila River Indian Community, on the outskirts of Phoenix, as their memories ebb and flow. Some occupy the bleachers, while others gather around tables to listen to President Joe Biden, who has come to offer a formal apology, on behalf of the federal government, for the establishment of boarding schools. Elders, their families and people like me — people who live with the consequences of the government’s actions — are gathered en masse for once. I can see the faces. Hear the voices. Weathered hands and tired eyes from history are standing before me.

I’m tasked with reporting for ICT, formerly Indian Country Today. In the sea of people, I spot my journalism mentor, Patty Talahongva, a survivor herself. She buzzes around the gymnasium, shaking hands and hugging other survivors. With her encouragement, I interview others and hear their stories.

I hear, “My grandfather was a student at Phoenix Indian … and I was a boarding school student.” That’s Idilla Stanley, a Tohono O’odham.

“I went to Phoenix Indian High School, and my mother and my late father went there, as well as my aunt, my mom’s sister, and then my sister and a couple of my cousins,” says Eleanor Masayumptewa, a Hopi.

Every participant, united by a common history and family bonds, gathers for the apology, which signifies the end of an important chapter in their lives.

Haaland, the interior secretary, is introduced by Susanna Osife, Miss Gila River for 2024-25. Dressed in traditional regalia, she confidently addresses the audience, expressing her commitment to her people.

“I’m here for my ancestors, for my people,” she says. “I’m here to give a stand and speak my voice [for] those who couldn’t speak before. I’m here because of my leadership. I’m here because I was taught that, generationally, we have to ensure that we are taking these opportunities for our next [generations], and me being here is a symbol of that. For my ancestors.”

Despite the historical challenges and the continuous trauma faced by survivors and their descendants, people who endured the boarding school system continue to greet the rising sun in the east each day.

Before my grandmother died in 2020, she created a sanctuary in her hogan, a traditional yet modern home my extended family built together. While I was an undergraduate at Northern Arizona University, I often visited her. She loved watching classic Western films, weaving rugs on her loom from the wool of sheep she had sheared, and occasionally taking walks through her garden, which was a sea of green in an unforgiving desert. She nurtured her peach trees, looked after an unusual spruce and frequently harvested large zucchinis, a common food item at our family’s dinner table.

Her home consistently welcomed visitors, and I remember family members conversing in Navajo, their laughter filling the air. As my grandmother’s time on Earth neared its end, I asked about her experiences in boarding school. Instantly, her demeanor changed, her expression became somber, and her gaze drifted, as if she had been transported back in time. The silence stretched on as she carefully chose her words in English, and I found myself holding my breath, anticipating a vivid narrative similar to those depicted in films.

But the remainder of our day was enveloped in silence. She did recall the moment her sister returned home to the female hogan on horseback, dressed in pristine white clothing and sporting a neat haircut with bangs. My grandmother had come back from the desert, where she was either sheepherding or working with livestock. Along with others, she welcomed her sister back home and stood in awe at how sharply her own appearance — in tattered jeans and worn cowboy boots — contrasted with her sister’s.

Now, as night falls, the hogan remains empty except for my older brother and uncle, who have settled there to honor my grandmother’s memory and their own presence on tribal land. The sunset happens quickly. The canyon carves through the desert terrain, uncovering the trails my grandmother walked during her time as a sheepherder. The thin clouds adopt a magenta tint, drifting and stretching across the sky as the sun slowly sinks into the earth, casting the world into darkness.