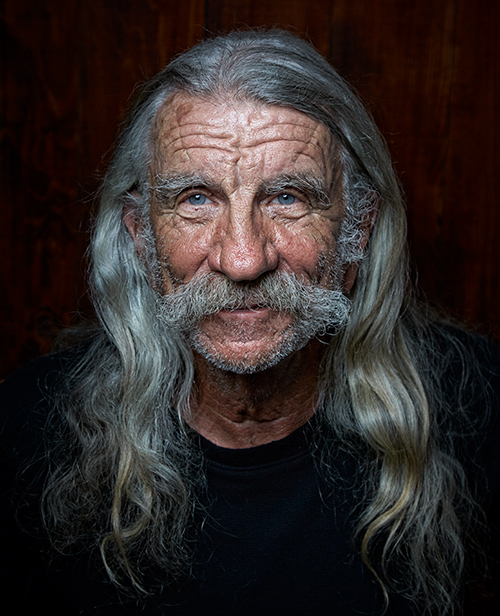

I haven’t seen Eric Gueissaz in 16 years, but his is a face that you don’t soon forget. With clear blue eyes, an epic nose that knows no end and a bushy, drooping mustache extending across his cheeks, he looks as if he belongs to another time — like someone out of a tintype portrait.

Gueissaz is, in fact, a throwback, part of a long tradition of outsiders — adventurers, artists, rogues and eccentrics — who discovered the Grand Canyon and then made the chasm their life’s great passion and cause. Like those who preceded him, this 75-year-old native of Switzerland and long-distance hiker would never presume to “know” the Grand Canyon. Instead, he revels in an endless journey of discovery.

“I look at the Canyon every day, and it’s still almost like seeing it the first time I was here,” he says. “People will ask what my favorite place is in the Canyon. I don’t have any. Everywhere I go that is a new place is just as important as the place that I saw before. The terrain is new. The area is new. You don’t ever ‘know’ it.”

Mike Buchheit, director of the Grand Canyon Association Field Institute, has known Gueissaz for 21 years. “I’d put him up there with some of the legendary long-distance hikers here,” he says. “Eric has seen a whole lot of the Canyon and taken some pretty ambitious and gnarly hikes. But he’s the furthest thing from a self-promoter. Eric is more of a poet-philosopher. If he comes upon some tourists in a chance encounter, he’ll share his passion and stories and make sure they’re set up for success.”

Gueissaz (pronounced “gay-suh”) and I arrange to meet outside Maswik Lodge, and I quickly spot him, gray ponytail trailing past his shoulders and arms filled with newspapers for his wife, Susie. She’s hanging out at Highland Mary, the historic 1899 mining claim, a few miles from the park boundary, where the couple live on the South Rim.

Gueissaz greets me warmly, and we climb into his pickup, then head down a dirt road that quickly leaves the park and crosses into the Kaibab National Forest, where he and Susie are the only year-round residents on the entire Tusayan Ranger District. Gueissaz says even though the road hasn’t continued across his land since the 1980s, visitors directed by outdated smartphone maps still arrive at his gate.

“They come down the road, and then they can’t figure out why it doesn’t go though. Technology is outpacing reality, and people just don’t get the message,” he says. Pointing at my phone, he adds, “It’s really strange how it works. They look at this thing and think it’s going to take them to heaven. It takes them to hell, that’s what it does.”

Mini-rant aside, Gueissaz is anything but a curmudgeon. Forty years of exploring the Grand Canyon — “up and over and around,” as he and his friends like to put it — and the decades-long creation of his off-the-grid ponderosa pine paradise have given Gueissaz a sincere appreciation of his good fortune and a rare, often whimsical wisdom: “We all know the pasture is always greener on the other side of the fence. True! But is it edible?”

“That’s one of the things you have to understand to get out of the Canyon when you’re hiking: The geology is going to save you. By knowing the geology, you can always figure a way out.”

— Eric Gueissaz

He’s a pleasure to listen to, thanks to a still-rich accent and a lyrical, free-form delivery that bobs and weaves, sometimes punctuated with a few favorite phrases (“So be it” and “There you go”) for emphasis, as the conversation ranges from the nature of time to Swiss dairy cows with nary a pause.

“The other day, I was driving the shuttle bus to the North Rim and telling the passengers stories about the Canyon,” he says. “One fella from Maine says, ‘You know, Eric, I don’t know you. And you don’t know me. But from what you said, you never could have dreamt all this, could you?’ ‘No,’ I said. ‘Never. Not in a million years.’ And that’s exactly right. To me, it’s wonderful. Sometimes you get more out of life without expecting or planning anything.”

The automatic gate balks as we arrive at Highland Mary. “C’mon, sweetheart, c’mon,” Gueissaz says. “Sometimes she’s stubborn. For the most part, she goes, but today is Sunday. So maybe she’s resting.”

Once granted entry, Gueissaz continues a short way to a stone house set in a clearing near a stand of old-growth ponderosas and a couple of hundred yards from the tracks of the Grand Canyon Railway. Gueissaz delivers the newspapers to Susie, his wife of 34 years, whom he met not long after arriving at the Canyon in 1972. Her parents worked for the Fred Harvey Co., and she grew up here. “I look at Susie and feel I just showed up yesterday, you know?” he says.

When he moved to Highland Mary in 1973, the house was little more than a shell, with no electricity, heat or running water. Originally, only the front and the chimneys were constructed of stone, but Gueissaz says he became obsessed with turning it into a true rock house. He gathered local boulders by hand, then, through trial and error, figured out the proper mud mixes and building techniques.

Trailed by Sparky, one of his three dogs, Gueissaz leads me to the vegetable garden, where his cat Lulu sometimes earns her keep by lying in the shade of the rhubarb leaves and waiting for unwary mice. He and Susie have mastered high-elevation farming and grow a surprising variety of crops — tomatoes, Swiss chard, beets, turnips, leeks and kale among them. “But gardening at 7,000 feet, oh, it’s a deal,” he says.

A wooden shed houses an inverter and batteries for the solar power system, and he collects rainwater and snowmelt, which are gravity-fed back to the house. We walk inside, where he shows off the greenhouse and its tropical, grotto-like shower. Just about everything on the property has a backstory: Some windows came from El Tovar Hotel, while the outdoor grill — which Gueissaz fires up for 200 guests during an annual Swiss independence celebration that can last for three days — once was part of the kitchen at Bright Angel Lodge.

He points out a green Eastern Windsor cookstove, circa 1920, brought years ago by a buddy. “It was mine to be had, so thank you very much,” Gueissaz recalls, before describing how the house came together over the decades. “A little bit here, a little bit there. Friends stop by and help you. You find old bricks, then some beams from another place, and go for it. Eventually? You really got something.

“Who would have ever thought of all this to become a reality? When, in reality, there was no reality to go this way?”

Exactly how a Swiss national from that country’s French-speaking Romandy region ended up living a latter-day frontier existence on the Coconino Plateau is a story with many chapters.

Born in 1940, Gueissaz grew up in Orbe, a small town north of Lake Geneva. Although Switzerland didn’t endure the ravages that other European countries suffered during World War II, Gueissaz came of age during a time of social transition as a generation of men, including his father, returned from the war. As Gueissaz puts it: “They took a deep breath for about 10 years, then were able to look back and ask about the true meaning of life.”

After serving his own compulsory stint in the military, Gueissaz asked similar questions before making a break from what he characterized as the still-entrenched ways of Swiss society. One day, he announced to his father that he had taken a job and was moving to Malmö, Sweden. “When I left Switzerland, I was 23, and everyone asked, ‘Why do you want to go there? You got everything here,’ ” he says. “Well, excuse me!” He stayed in Scandinavia for about three years; “then, the horizon got even farther away, and there you go. So I came to this country.”

Gueissaz figured he would live in the U.S. for a few years, which would give him time to learn the language, experience the culture and travel before he moved on to yet another destination. He worked in restaurants, first in New Orleans, then Salt Lake City and finally San Francisco, as it dawned on him that the U.S. is not only a nation, but a virtual continent, too. Arizona alone is seven times larger than Switzerland.

“Everywhere I went in the United States, it was different, especially in the ’60s and ’70s. Society-wise. Culture-wise,” he says. “But after a while, I decided, Enough with cities. Is this America? No. It isn’t. It can’t be. There’s gotta be more than this.”

He contacted a friend in the food business who suggested he call someone at the Canyon about a job, and soon, the Fred Harvey Co. hired him. He eventually worked as sous-chef at El Tovar and later owned and operated Café Tusayan for 10 years.

Gueissaz knew of the Rockies and the Sierra Nevada, but the Grand Canyon hadn’t figured in his imagination while he was growing up. “I first saw the Canyon and this region, and it was like, Whoa! What is this? At first I couldn’t comprehend it,” he says. “How did this place come about? How is this possible? Did someone take a dagger and, from one end to the other, dig in the dirt? Then I learned about the geology. That’s one of the things you have to understand to get out of the Canyon when you’re hiking: The geology is going to save you. By knowing the geology, you can always figure a way out.”

Gueissaz didn’t explore the Canyon’s depths right away. But his first trip was unforgettable. In February 1976, Gueissaz and four friends hiked down the Hopi Salt Trail to the Hopi Sipapu, a sacred spot near the Little Colorado River. The weather was good as the group descended from the rim along a rough path. Right away, however, Gueissaz slid and landed smack on a cholla. “I picked needles out my butt for a while,” he recalls. “So be it.”

They reached the Sipapu without any other incidents. Gueissaz describes seeing a domed cavity with prayer feathers and bubbling water fed by the Sipapu’s connection to a volcanic thermal system. His friend Chuck got ready to photograph the Sipapu, but another friend, John, warned that would be sacrilegious. “Chucky said, ‘Aw, hogwash, man; I’m going to take pictures,’ ” Gueissaz says.

The group camped under the stars. “I’m always a light sleeper in the outdoors,” he says. “I sleep physically, but mentally I’m always aware, and about 3 in the morning, I feel something and think, Oh, it’s starting to rain. We found shelter under an abutment of wall and made a fire. Then, at 6, I looked down to the river and saw ducks flying upstream and thought, Uh-oh. Something is happening here.”

Snow started falling on the Little Colorado. By the time the group reached Chuck’s truck, a foot of snow had piled up on the rim. Visibility was close to zero, and at first they couldn’t get the camper open. Eventually, the group managed to reach Cameron to fuel up, then drove in four-wheel-drive back to Highland Mary, where, at 3 the next morning, the truck ran out of gas as they pulled up to the house.

“From that day on, I was hooked,” Gueissaz says. “It was nice and sunny. Then someone takes some pictures and everything was different? There’s gotta be more like that. Sure enough, there always was.”

Though admittedly “no spring chicken,” Gueissaz still explores the Canyon on hikes that can last up to 10 days. While Freckles, another one of his three cats, dozes and a classic cuckoo clock calls every 15 minutes, we settle into some chairs, drinking coffee and munching on cookies made with zucchini from the garden, as Gueissaz weaves more stories of his adventures.

Two years ago, he and his friend Bill set out on a hike on the Esplanade. The pair trekked down Kanab Creek and decided to go up an unnamed canyon because it had been raining and they figured the Esplanade’s potholes would be filled with water.

The pair came to an area with fresh water and cottonwood trees, then stopped for a snack. Gueissaz looked around and suddenly, on an opposite wall facing north, spotted “a big, red painting of an ancient person.” The whole area was filled with petroglyphs and pictographs that Gueissaz assumed very few people had seen.

“Like I said, the Canyon forces you to [go] up and over and around to see what else is there,” he says. “There’s always the unexpected. It emphasizes the unknown. That’s the beauty of this place. You never know what you’re going to find. And sometimes you find nothing of interest. But the journey in between the two points is what’s always of interest. It’s a wonderful place. A place of sanity that has kept me healthy, real and sane.”

Then he adds: “There’s this little light that should never be extinguished, a curiosity. That way, there’s always a wonderment about things. It’s what keeps a life a life.”