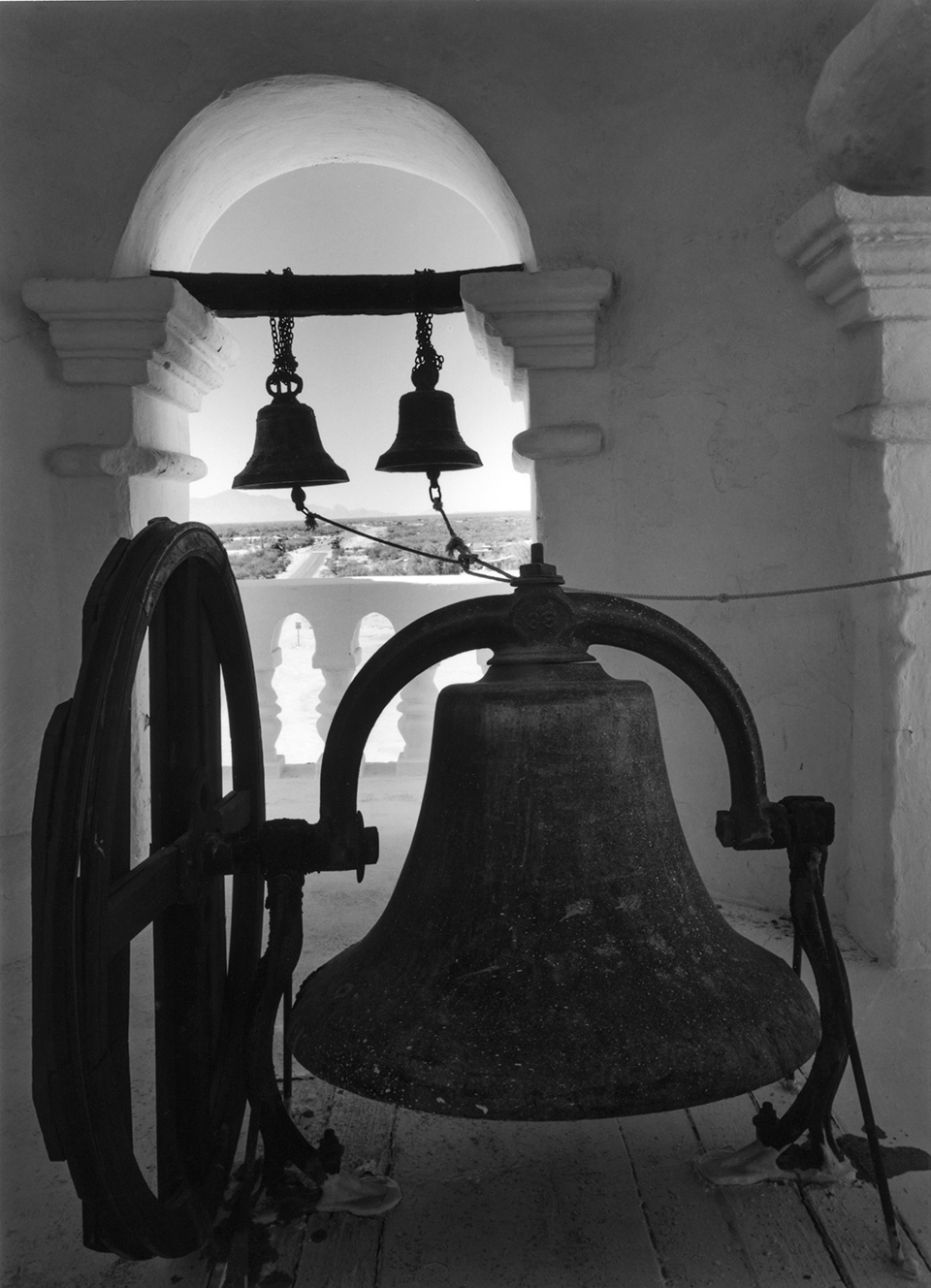

Back in the summer of 1977, John Schaefer would sometimes slip out of his Tucson office in the middle of the workday, drive the dozen-odd miles to Mission San Xavier del Bac and spend a couple of hours photographing the lovely 18th century church. Some evenings, he would return after dark, use the key that the parish priest had remarkably entrusted to him, set up his lights and 4x5 view camera inside, and spend several more hours photographing the church’s astounding congress of carved saints and angels. These photographic interludes served as a welcome foil to the monumental stresses of Schaefer’s day job — president of the University of Arizona — but they imposed another kind of pressure.

Schaefer, at this point still an avocational photographer, had been commissioned to produce a book of mission photographs to replace one that had recently gone out of print. A book by Ansel Adams.

Schaefer recalls his first promise to himself that summer: I will not take any of the same pictures Ansel did. For obvious reasons.

Obviously, any such book born in Adams’ umbra would remain in that towering shadow — or maybe not. At least one of Schaefer’s images from that summer has become an iconic photo, reproduced endlessly: the mission’s transept dome glowing like a bulb in the midday summer sun, framed in the curved hand of an arch in the north court. It’s a study in geometric grace, a counterpoint of brilliant light and many tonalities of shade, a frozen waltz of an architecture of curves.

Adams made a 1968 photograph from almost the same vantage point but included many more bits and pieces of the building in it. His photo demonstrated the mission’s breathtaking complexity, while Schaefer’s distillation highlighted its breathtaking beauty. Both photos are works of art; it’s a fool’s errand to rank them.

Not many budding photographers would care to risk following a giant like Adams, but Schaefer has never been shy about taking on challenges.

When he became president of UA in 1971, at the age of 36, the college had a reputation as a minor-league, fun-in-the-sun state university with just a handful of standout departments. Schaefer undertook a wholesale transformation, hiring star faculty and imposing higher standards for promotion and tenure. He wanted to vault UA into the top ranks of research-oriented universities. He soon collected a tail of critics who carped that he was moving too fast, spending too much and demonstrating way too little regard for the stately collaborative processes of academia. Some called him arrogant. The accusation still seems to rankle him, although he’s now willing to thoughtfully parse it.

“When I became president of the university,” he says, “I’d been to a lot of really fine schools — Illinois, Caltech, Berkeley — and I knew Arizona wanted to be that kind of university. I was going to do everything I could, come hell or high water, to do what was needed.

“Honestly, it takes a bit of arrogance to think that you know better than anyone else and you’re going to do it. When I became president, I was going to give it my all, and if they didn’t like it, they could fire me. At the end of the run, I think people said, ‘Yeah, it did change for the better.’ ”

One of Schaefer’s controversial moves involved photography. In 1974, the UA Art Museum had assembled a major show of Adams’ prints, which gave Schaefer an idea: No other American university except the University of Texas was taking photography seriously as a form of art and cultural documentation, and he thought UA could step into that role. Ten minutes into the show’s opening reception, Schaefer approached Adams with an audacious ask: How would you like to give your archives to the university? “I was young and naive,” Schaefer recalls, “and he was a little stunned.” But Adams agreed to talk, and Schaefer went to visit him for a week in California. They negotiated, they went out shooting together, they became friends — and Adams agreed for his life’s work to go to UA’s Center for Creative Photography. Four other significant photographers joined in: Wynn Bullock, Harry Callahan, Aaron Siskind and Frederick Sommer. (The center now holds some 110,000 works by 2,200 photographers.)

Schaefer spent around $500,000 on the founding collection, and he says that although it came from private money through the UA Foundation, “it came close to getting me fired. The Legislature said, ‘What are you spending this kind of money on photographs for?’ Clark Beane, who was then CEO of the Arizona Bank, went to the Legislature and told them, ‘You guys don’t realize what just happened. This is a great coup.’ That quieted things down.”

Schaefer’s passion for photography grew through a complicated weave of his career in science (he was a professor of chemistry before becoming UA’s president), his wide-ranging interest in the humanities, and his life story.

His parents had emigrated from Germany in the 1920s and settled in New York. The family had little money, so visits to the old country were out of the question. Schaefer learned about his extended German family through the photographs they sent, and that became the embryo of his interest in photography. When he earned his Ph.D. from the University of Illinois, his parents gave him a Zeiss Ikon Contaflex — his first serious camera. He still has it.

As a UA faculty member and then president, Schaefer began exploring unpredictably varied photographic subjects, delving into each with a consuming intensity — something he’s tended to do with every interest in his life. First it was bullfights in Nogales, Sonora, then desert landscapes, San Xavier, and the Tarahumara and Tohono O’odham cultures. Until 1979, he worked only in black and white. “Color can overwhelm the senses with concepts like ‘pretty,’ ” he says. “Black and white makes the photographer and viewer go beyond surface impression. I still think that [black and white] is better at conveying mood.”

But that year, UA anthropologist Bernard “Bunny” Fontana invited Schaefer in on a book project documenting the history and culture of the Tarahumara people of northern Mexico, and it veered Schaefer temporarily toward photojournalism. He left the 4x5 camera at home and shifted to 35 mm and medium-format cameras loaded, for the first time, with color film. One of the action photos in the book shows how he had developed an instinctive eye for the telling detail — a minor element in a composition that contains a story in itself. The photo illustrates two Tarahumara girls racing, and instead of the expected view of them from the front or side, we see them from behind. The viewer’s eye moves inevitably to the bare foot of the trailing girl, her sole the brightest object in the composition — and there we learn that running is central to Tarahumara culture.

Schaefer left the university in 1982 to run the Research Corp. (now known as the Research Corporation for Science Advancement), a foundation that supports research in the physical sciences. His photography took another turn, this time into the miniature world of cactus flowers. He was fascinated not only with their color and geometry, but also with the self-contradicting character of the cactus plant. Bristling with forbidding armament, each cactus, once a year, will burst into bloom with an enticement that sweetly begs, “Come here (and pollinate me).” Another new photographic idea came into play: He brought a pack of black construction paper to each shoot and fabricated a black “necklace” around each plant, eliminating background clutter and dramatizing the flower’s color. Another book, A Desert Illuminated: Cactus Flowers of the Sonoran Desert, appeared, and last year, the U.S. Postal Service issued 10 commemorative stamps using Schaefer’s images.

Schaefer’s original plan for cactus flowers didn’t stop at the borders of the Sonoran Desert. “I decided I was going to photograph every species in the world,” he says. “It became a driving passion. There’s a cactus farm about a mile from my house here, and I began going over there every day.” He soon learned, though, that there are some 3,000 cactus species in the Americas alone, and the flower project shrank to a more manageable dimension: Arizona. But it didn’t diminish the standard of quality he demanded from himself.

The question occurs: Where does this drive come from, this intensity that seems to turn every interest into a consuming passion? Normally direct and confident of his words, Schaefer hesitates a little, as if he hasn’t often been asked to reflect on his own character.

“I guess when I get serious about something, I really want to do it in a way that makes a difference,” he says. “I believe that life is a privilege. You’re not here to take up space; you’re here to try to make a difference. I want to do my best.”

And on photography specifically? “A lot of people who consider themselves photographers take pictures; they don’t make photographs,” he says. “Making photographs is a very different mindset. It means you really have to see. There’s a difference between looking and seeing. When you’re just taking pictures, you’re not getting into the essence of what you’re looking at, and understanding it.”

It comes as not much of a surprise that Schaefer, at 85, has recently moved on to a new photographic obsession — hummingbirds — and that he’s embracing cutting-edge technology to allow us to see them in a new and revealing context.

“I guess when I get serious about something, I really want to do it in a way that makes a difference.”

— John Schaefer

Nearly everyone, he says, photographs hummingbirds hovering and poking their needle-like beaks into flowers. Very pretty, but do those pictures make a difference in our understanding? In pursuit of something deeper, Schaefer has been setting his camera on a tripod very close to a hummingbird feeder — generally in his own yard — and, when a bird approaches, firing a battery of three strobes at an extremely brief duration of one-30,000th of a second. This instantaneous zap will expose the bird, but the camera records nothing in the ordinary daylight beyond it. The background remains black, just as with the cactus flowers’ paper bibs. While it seems counterintuitive, artificially illustrating the birds apart from their environment helps us understand more about them — their extravagant color, their flight dynamics. Maybe we even think we see an inkling of their personalities.

More than occasionally in his long career as a scientist and executive, Schaefer was accused of being impatient. So it seems incongruous at first to watch him sitting silently for a couple of hours, waiting for hummingbirds, Bluetooth shutter trigger in hand, with nothing happening. He doesn’t fidget. He doesn’t complain. The patience, it seems, derives from that deep understanding of the subject: The birds are on their own schedule and have no interest in the human agenda.

“A lot like fishing,” Schaefer muses, not discontentedly. “You just wait for something to happen. Or not.”

• To learn more about the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, visit ccp.arizona.edu.