William Randolph Hearst was a man accustomed to getting his way. Heir to a mining and ranching fortune worth hundreds of millions in today’s dollars, he was a media mogul, art collector and two-term member of Congress. He ran for president in 1904, finishing second for the Democratic Party nomination.

Rich and powerful, Hearst stood 6-foot-3 and was anything but shy about throwing his weight around. He clashed with both Theodore and Franklin Delano Roosevelt and played kingmaker, and his exploits inspired Citizen Kane, considered by many the greatest film ever made.

Biographer David Nasaw wrote that for decades, Hearst “ruled his empire as autocratically as his heroes Julius Caesar and Napoleon Bonaparte had theirs. He had trusted no one [and] rejected suggestions that he share power or delegate decision-making.”

In other words, there was a reason many in Hearst’s time called him “The Chief.”

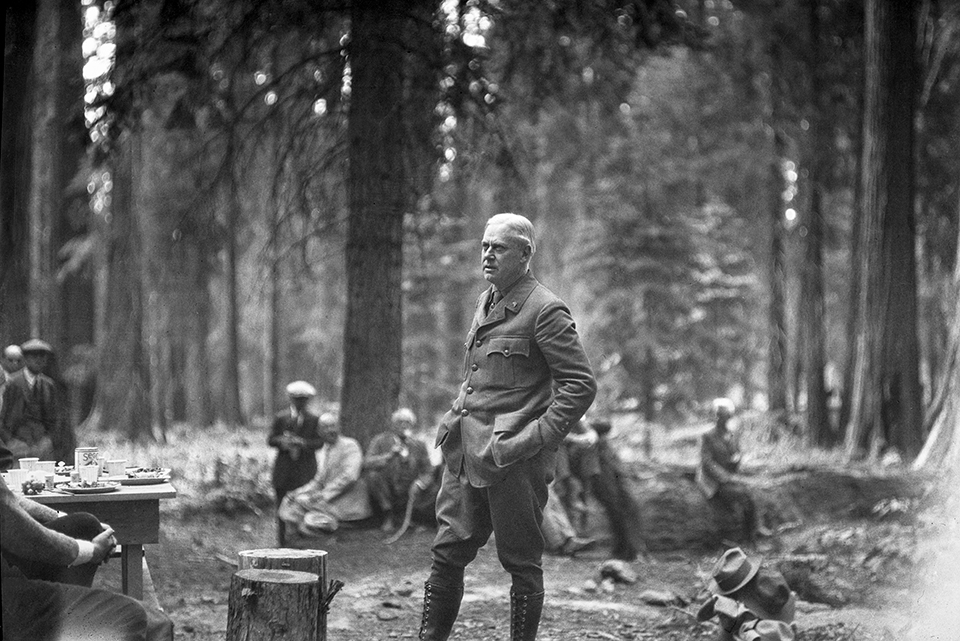

The National Park Service’s first director, Stephen Tyng Mather, had a few things in common with Hearst. The scion of a prominent Puritan family that came to America in 1635, Mather also was born in San Francisco and stood over 6 feet tall.

For a time, he worked as a reporter at the New York Sun, the rival to Hearst-owned newspapers in America’s largest city. But while Hearst’s fortune came from silver mining, borax made Mather a millionaire, and he’s credited with creating the famous 20 Mule Team brand.

Mather achieved his success even while battling bipolar disorder, which spiraled him into the darkest of places. As Horace M. Albright, who succeeded Mather as Park Service director, observed: “His energy and exuberance, which accomplished so many great things, could turn to deep, silent, suicidal depression with little warning.”

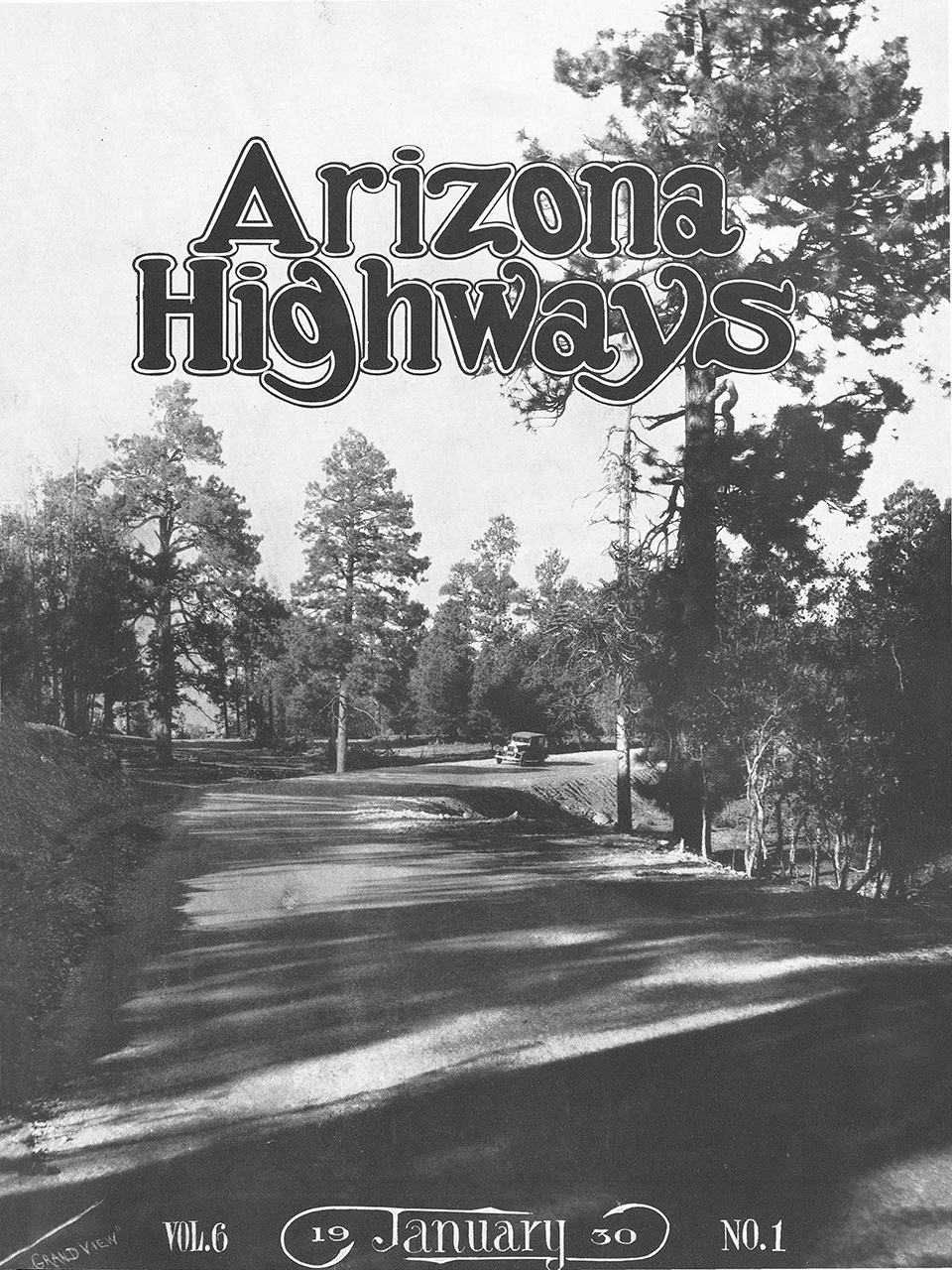

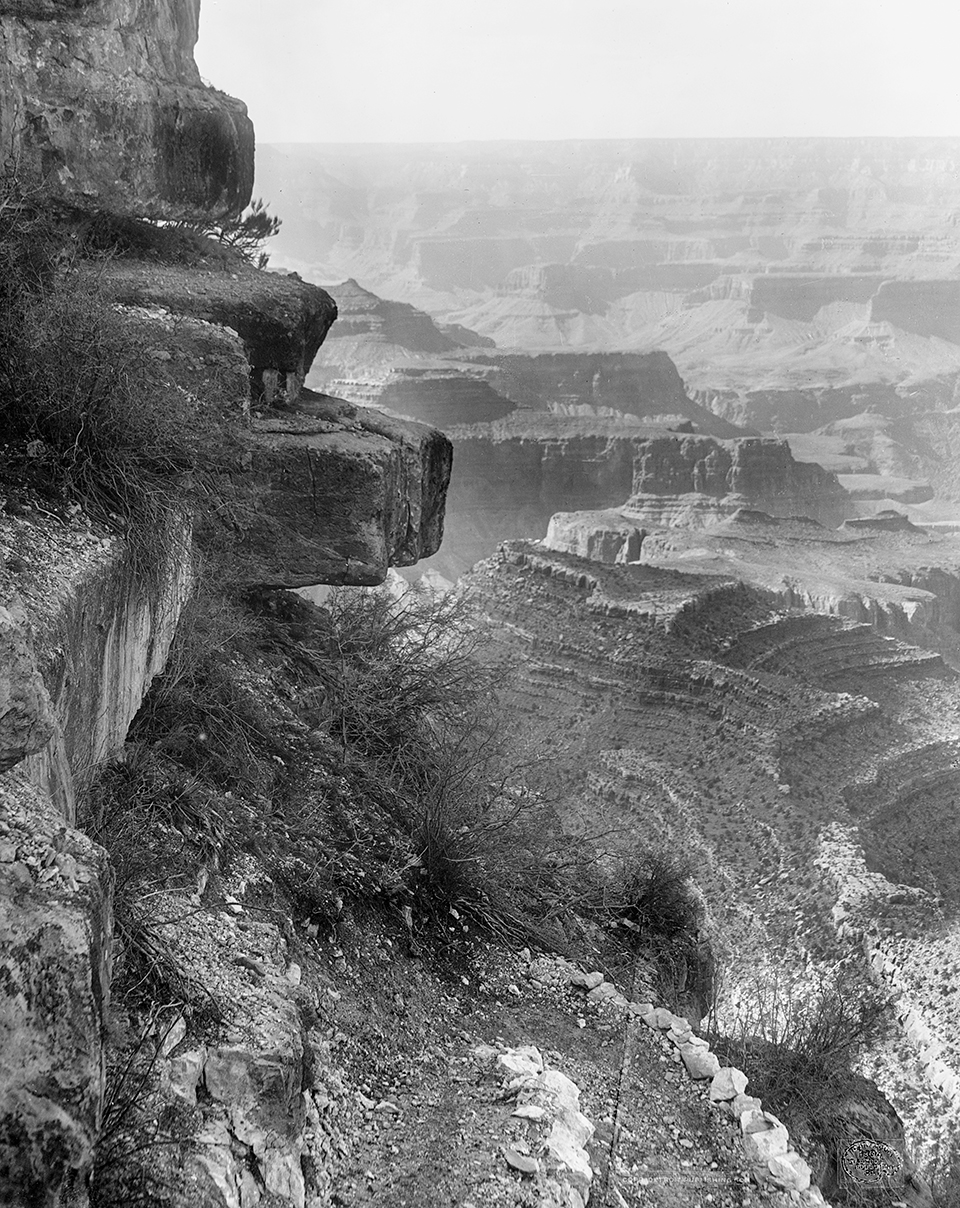

If the Arizona ties of these men seem limited, Hearst and Mather faced off at a site worthy of their stature: the Grand Canyon’s 7,400-foot Grandview Point. Hearst purchased the property in 1913, and a subsequent struggle for one of the South Rim’s loftiest promontories played out for more than 20 years — and at the highest levels of American power and influence.

Hearst, for his part, knew what he had at Grandview: “I think it is the best on the Canyon.”

Which brings us to Canyon legend Pete Berry. His grave marker in the Grand Canyon Pioneer Cemetery states the basics:

P.D. BERRY

Born–May 1856

Died–Sept. 1932

A whole lot happened in between. A Colorado miner, Berry came to Arizona seeking vengeance after the murder of his brother John, proprietor of Flagstaff’s San Juan Sample and Club Room, a saloon touting gambling tables that never closed.

John was shot and killed during a brawl between two local ruffians and other saloon patrons. In a bit of frontier-style karma, vigilantes broke into the jail where the ruffians were taken, then killed the pair. Upon arriving in Flagstaff, Berry supposedly declared, “Boys, you saved me the job.”

But that bluster doesn’t square with Canyon photographer Emory Kolb’s recollections of Berry. In a handwritten 1973 letter, Kolb — who apologized, “as I am now 93 years old and forget a lot” — characterized Berry as a hardworking and honest man, a recovering alcoholic with good carpentry skills and a slow manner of speaking. “When starting to tell a little story, it always took him half an hour or more to get it out,” Kolb wrote.

Settling in Arizona, Berry soon married his murdered brother’s beautiful widow, May, then sought mining opportunities at the Canyon. He partnered with business-man and future U.S. Senator Ralph Cameron and his brother Niles, and they would go on to literally leave their mark on the Grand Canyon.

Berry and the Camerons expanded an old Indigenous path from the rim to Indian Garden (now Havasupai Gardens) and opened the Bright Angel Toll Road, today’s Bright Angel Trail. And in 1892, Berry started constructing the Grandview Trail to boost production from the Last Chance Mine, the Canyon’s most significant copper vein. Each day, as many as 10 mules would each haul 200 pounds of high-grade ore 4 trail miles and 2,500 vertical feet from Horseshoe Mesa to Grandview Point.

The mine proved more productive than profitable, and it also cost Berry his marriage. A fan of neither the Canyon life nor Berry’s frequent absences, May ran off to Tucson with a traveling salesman. By some accounts, she took their son Ralph (named after Cameron) with her, and Berry then paid $100 to one of the Camerons to kidnap Ralph and bring him back.

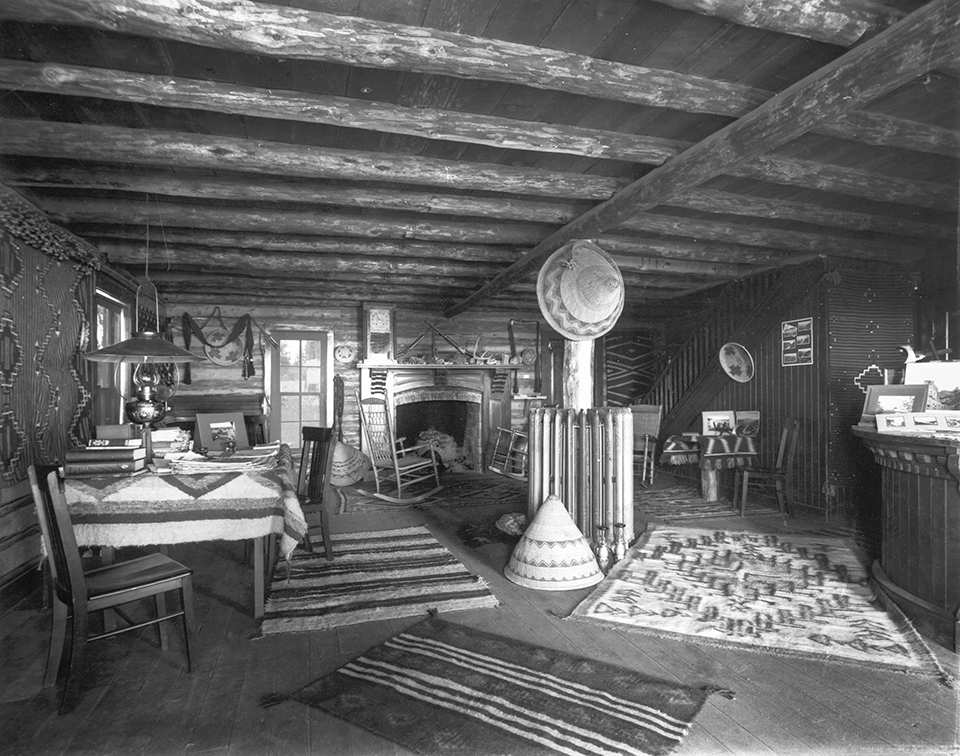

Berry remarried and opened the Grandview Hotel, the Canyon’s first major lodging facility. “The Only First-Class Hotel at the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River in Arizona,” declared a rate card advertising nightly stays for $2.

Guests arrived by stagecoach from Flagstaff to a hotel built of ponderosa pine. And although hardly opulent, the Grandview had its appeal. In a 1976 history, park ranger Sonja Sandberg cites a Yelp-worthy review: “One of Europe’s many counts described his stay at the Grandview as ‘restful … charming … rustic … good food.’ ”

The hotel prospered until the Santa Fe Railway began running from Williams to Grand Canyon Village in 1901. Berry tried to hold on, shuttling guests 11 miles by stagecoach from the depot, but he couldn’t compete with the convenience of the village’s Fred Harvey accommodations.

According to Sandberg, Berry suffered a major setback when the U.S. Forest Service, which administered what then was the Grand Canyon Forest Reserve, took away access to a water source on reserve land, a move apparently in deference to Santa Fe and Fred Harvey interests. In 1913, Berry finally sold the hotel and its land for $26,000 and another 160 acres of property for $49,000. To a guy named Hearst.

“Berry’s anger was typical, if a bit more extreme than most,” a 2000 administrative history of Grand Canyon National Park concludes. “He refused time and again to succumb to [railroad] purchase offers, choosing instead to sell to William Randolph Hearst, who he believed, correctly, would prove a thorn in the government’s side.”

Hearst was no stranger to Arizona. His father, George, had owned the San Pedro River Valley’s Boquillas Land Grant, and Hearst inherited that holding before selling it in 1901. And while trying to drum up support for his 1904 presidential bid, he traveled through Arizona by private railcar during a 12-day whistle-stop tour officially named the “Congressional Trip by Special Train Through the Southwestern Territories in the Interest of Statehood.”

More poetically described by The Arizona Republican as a “comet-like journey through the territory … o’er mountain, valley and plain,” the 1903 tour stopped at the Canyon. It featured U.S. senators, 17 members of Congress and marching bands, with Hearst newspaper reporters and photographers covering the extravaganza.

Statehood advocates deified Hearst. Tucson’s Arizona Daily Star wrote, “This modern Hercules of the press with his associates will battle to crystalize the facts into a law creating Arizona into a sovereign commonwealth. This will surely come to pass. Let us be grateful.”

Hearst’s Grandview purchase came a year after Arizona statehood, and some assumed he’d establish residency, then run for U.S. Senate. Anything was possible considering Hearst’s serial candidate history, which had included campaigns for New York governor and New York City mayor.

But Hearst was also an inveterate builder. Flagstaff’s Coconino Sun concluded that the site’s “wonderful setting” would “naturally convince the casual observer that the project is more than one of securing a home on the brink of the Canyon.” The Hearst-owned Los Angeles Herald Examiner described Hearst’s intentions to build a lodge and a private residence at Grandview, while others gossiped that he “bought the place for a million-dollar bungalow.”

In a 1926 note to architect Julia Morgan, his collaborator on California’s Hearst Castle, Hearst mused about a Hopi-style house at Grandview. He thought it would better fit the setting than a stone structure but worried, “It is just a mud house. … Perhaps we could mix the mud with something that would keep it from disintegrating into dirt.”

He added, with rambling glee, “There is a certain attractiveness in the Hopi style of architecture. … Of course, it would be as full of ‘atmosphere’ as a poisoned pup. We could have Indian paintings on the wall and Indian rugs on the floor — and Indian fleas all over us!

“I can hardly wait until the house is done. It is going to be romantic and itchy.”

Hearst’s acquisition came just a few years before the establishment of the Park Service and Mather’s appointment as its director. Summarizing his philosophy, Mather declared, “The Yosemite, the Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon are national properties in which every citizen has a vested interest; they belong as much to the man of Massachusetts, of Michigan, of Florida as they do to the people of California, of Wyoming, and

of Arizona.”

The decadeslong campaign to designate Grand Canyon National Park was also nearing completion despite considerable local opposition, including that of the powerful Ralph Cameron. Hearst also had concerns, and Albright suspected he wielded his influence behind the scenes to block the designation. Albright concluded Hearst was “afraid the National Park Service would take Grandview and that Berry property away from him. That’s why he didn’t want it made a park.”

Mather was philosophically opposed to private inholdings and coveted Grandview, especially because Hearst remained cagey about his plans. A yearslong stalemate ensued as Hearst sought a land exchange and Mather proposed that Hearst never develop the land commercially, then donate the property upon his death.

They did find some common ground. During planning for construction of Desert View Drive, a deal allowed the park to build its preferred route across Hearst’s lands. Then, something remarkable happened: After years of sporadic, indirect communication, Mather, Albright and Hearst met in San Francisco. Albright recalled, “[Hearst] was just as gentle as a baby. Kindly eyes and friendly smile and charming and pleasant.”

Hearst told the park officials his only desire was to build a museum for his Indian artifact collections. But a 1936 Morgan design shows a Mission Revival-style hotel that would have been the Canyon’s grandest structure, with twin bell towers, balconies overlooking the Canyon and alcoves for santos above the entryway.

Mather’s health problems led to his resignation in 1929, and he died the following year. Under Albright’s leadership, the Park Service continued to target Grandview. The ongoing dispute played out amid Hearst’s growing financial troubles and the Roosevelt administration’s concern about what officials characterized as the “erratic” and “unscrupulous” mogul’s “degrading influence on the American people” and potential impact on the 1936 presidential race.

In 1939, as the Park Service sought the land through condemnation proceedings, Hearst still refused to sell. Arizona U.S. Senator Carl Hayden called Interior Secretary Harold L. Ickes and argued that Hearst had been assured long ago that the property would never be taken against his wishes. Ickes held firm, telling Hayden the park “really ought to have this land which Hearst has never used and that the thing to do was to agree to [a] fair price.” Hayden responded, “Hearst hates to give up any property that he owns.”

That September, the condemnation suit was finally filed to acquire 207.7 acres of Hearst’s Canyon properties for $28,950. While there were legitimate local concerns about private property rights and the loss of tax revenue, the rhetoric veered to extremes. “The Stink on the Brink” was among the milder characterizations. The Williams newspaper called the action “imperialistic,” adding that the move “may have been stimulated by the aggressions of dictators of Europe” before likening the Park Service to Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. Others worked in references to Nazis and fascists for good measure.

The bottom line: Hearst demanded $392,100 for his properties, but a federal judge awarded him $85,000. Grandview Point officially became part of the park in 1941.

Today, Mather Point immortalizes Mather, while the park’s Horace M. Albright Training Center honors his successor. You can also still hike the Grandview Trail built by Berry, who remains a fixture in Canyon lore. He moved to a nearby ranch, still dreaming of the big score that had always eluded him. Years earlier, Berry had known a gang of horse thieves, one of whom was mortally wounded in a shootout with law enforcement. The dying man told Berry he had buried a copper kettle filled with gold on the Tanner Trail. Berry never forgot and, as an old man, planned to head down into the Canyon one last time to recover the treasure. He never made the trek.

Meanwhile, Berry’s Grandview Hotel enjoys a glorious afterlife. After the hotel’s demolition, Hearst salvaged the building’s ponderosa pine logs, which were repurposed for Desert View Watchtower’s Indigenous-inspired lobby ceiling.

Hearst never did build his Hopi dream house at Grandview. But somewhere, he might be enjoying a satisfied laugh while Mather curses the fates. Because deep within the Canyon, along the north side of the Colorado River, there’s an old asbestos mine. A family inherited the land from a prominent ancestor who acquired it decades ago. That land is the Hearst Tract — the only private inholding within Grand Canyon National Park’s original boundaries.