Jack Dykinga scared the hell out of me.

I grew up in a three-newspaper household in a four-newspaper town. Maybe I didn’t pay quite as much attention to bylines as to box scores, but journalists were my heroes, right up there with ballplayers. Mornings began with the Chicago Sun-Times — tabloid in design but no gossip rag, the crusading alternative to the staid Chicago Tribune of Gothic Michigan Avenue headquarters grandeur and “Dewey Defeats Truman” infamy.

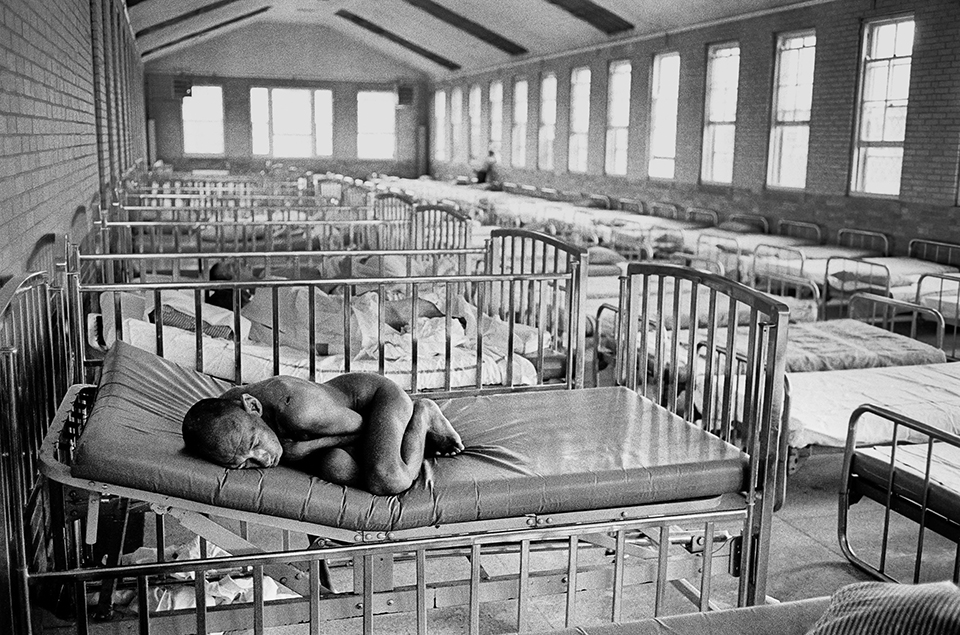

On a Sunday in July 1970, I went straight to the back page for the sports headlines, only to see that the Cubs and White Sox had both lost, before flipping the paper over to the news section. That’s when I saw Jack’s black-and-white photos from a pair of psychiatric facilities. The pictures, the critical component of a five-part investigative series, graphically revealed living conditions akin to something out of a 19th century asylum.

The misery is overwhelming. Unclothed residents stare vacantly from hard benches while another curls up on a bare mattress in a row of crib-like beds that fill a dormitory hall. One young man, grimacing, covers his eyes and grabs at his head. Another sprawls on a bare floor while janitors wielding their brooms stand in the background, impassive and ignoring the horrors before them.

Jack’s images went directly into my 10-year-old brain’s closet of nightmares, right up there with The Birds, Lord of the Flies and a mass murder a few blocks from my South Side house. But in 1971, when Jack won the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography for those images, it was a matter of civic pride that a Chicago guy had taken home the award.

Today, those black-and-white photos are not the images most people associate with Jack, a longtime Arizona Highways contributor renowned for his Sonoran Desert and Colorado Plateau shooting. Photographer and author John Shaw, one of many to sing his praises, describes Jack as “the best color landscape photographer that I’ve ever seen. Ever. I’ve never seen images like his from anyone else that are as powerful and well composed and put together.”

Based in Tucson since 1976, Jack has brought the splendors of the Southwest to a worldwide audience that might previously have dismissed this arid country as lifeless wasteland.

“You don’t get a sense of barren or desolate places,” says Rebecca A. Senf, chief curator at the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona and author of Making a Photographer: The Early Work of Ansel Adams. “I think of the Ansel Adams pictures of Death Valley. He was really playing up those qualities of barrenness and desolation and isolation to create a sense of drama. Whereas Jack Dykinga’s drama is much more subtle, and it’s coming from a much more emotional place.

“He creates that drama with light and color and abundance and strong compositional shapes, filling the frame with a sweeping arm of a closely framed saguaro. I think of these full, rounded shapes of brittlebush plants: beautiful, loping yellow globes in the landscape. Or a pattern of tumbling pieces of petrified wood that are contrasting against mud hillsides, or curving sandstone formations in all of these shades of orange and red. There’s a real sensuousness about the way he treats the landscape.”

I came West after college and began seeing Jack’s photography: gorgeous shots of Baja California boojums twisting against magenta skies, close-ups of agaves and barrel cactuses and saguaros, almost abstract yet so precise in detail that I thought touching the spines in the photos could draw blood. His is a remarkable body of work: ugliness and beauty, humanity at its worst and nature at its most magnificent.

Tucson writer and environmental advocate Bill Broyles is a longtime friend of Jack’s, and the two have spent many nights around campfires while exploring Arizona and Mexico. He marvels at the sweep of Jack’s career. “Jack is able to take a particular plant or boulder or cliff or water spring and make that place the most beautiful, or the most rugged, or the most enticing, or the most revealing place in the world,” Broyles says. “Yet he can shoot the entire view across the Grand Canyon, with the colors, layers, and the clouds and the lightning, and make that your place, too.

“His photography has evolved from black-and-white street shots in Chicago, and then he came out here and was photo editor at the newspaper before deciding he wanted to be a Colorado River rafting guy. ... How do you go from street shots to large-format color? It takes an incredibly adventurous spirit to make that work.”

To Jack, though, those pictures are not as different as they appear to be. “They’re all decisive moments; it’s just that some moments are farther apart,” he says. “That’s where the patience comes in, and it’s also where the knowledge of your subject comes in. And both of those qualities are journalistic.”

Jack opens the door to his home, an early-2000s, red-tiled roof house below Pusch Ridge with a patch of undeveloped desert just beyond the backyard wall. He’s taller than I expected, a fit 78, with an open face shadowed by a tightly cropped beard. What remains of his hair is cut close along the prominent dome of his head. Jack seems like an unlikely source of childhood nightmares, and now we’re just a couple of Chicago guys sitting around, talking about Chicago.

Jack grew up in the leafy western suburb of Riverside, somewhere on the other side of the metropolitan universe from my neighborhood near the steel mills and the Indiana state line.Riverside gets its name from a setting by the banks of the Des Plaines River. No cookie-cutter suburb, the town was planned in the mid-1800s by famed landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, and its park-like atmosphere, blending urban and natural features, earned the suburb a spot on the National Register of Historic Places.

The son of a railroad worker and a telephone operator, Jack was raised in a bungalow 300 feet from the train tracks. But there was beauty in town and nature nearby, as well as, quite literally, lions and tigers and bears at the world-famous Brookfield Zoo, just a few miles away. Jack looked out from his high school to the trees of a forest preserve and searched quarries for fossils. A June 1954 photo in the Tribune shows an 11-year-old Jack and two friends fishing from a nearly horizontal tree limb suspended a few feet over the Des Plaines. Jack’s feet dangle in the water, a glimpse of the bygone days of free-range childhoods.

“All of that was huge,” he says. “By the time I was born, my parents were both in their 40s, and they were not as doting.

I could wander pretty freely, and back then, there were prairies in western suburbs where I would collect garden spiders and snakes. I was able to go out and be curious. It sort of perked my interest in wild places.”

Although Jack’s boyhood seems idyllic, he faced a hidden challenge. Long before it was commonly diagnosed, he struggled with dyslexia. Reading proved difficult, and he graduated in the bottom quarter of his class. But Dick, Don and Ernie, his three older brothers, taught him how to use a 35 mm camera. For a struggling student, photography proved to be a lifeline.

Jack learned processing and printmaking at his high school newspaper. Working nights as a freight house worker with a predominantly Black crew, he unloaded rolls of carpet from boxcars, expanding his outlook beyond the sheltered suburbs. He socked away enough money to buy a Nikon, and then, a picture he shot of a football game won first place in a national competition sponsored by Look magazine.

Jack caught a break after graduation when the owners of the camera shop where he was spending all of his pay helped arrange his first professional job. It was as an assistant to photographer Mike Rotunno, one of those only-in-Chicago characters straight out of a David Mamet fever dream. After shooting for local newspapers, in 1927, Rotunno established Metro News at Midway, where he specialized in getting photos of anyone who was anyone arriving at Midway Airport: Hollywood stars (Marilyn Monroe and John Wayne), politicians (every president from Calvin Coolidge to Richard Nixon), world luminaries (Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, who later became Pope Pius XII). Al Capone reportedly took a dive when a Speed Graphic flash startled him, and Rotunno used to hang out with Harry Truman over ice cream sundaes and even attended the 33rd president’s 80th birthday party.

Jack bagged his share of celebrities, too, from Nixon to the Beatles, and broke the news to deplaning singer Andy Williams that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated. Delivering prints introduced him to newspaper photo staffs, and, after applying for a Tribune lab job, a 20-year-old Jack got hired as a staff photographer.

He entered a newsroom still rooted in the classic Chicago newspaper world celebrated in The Front Page, joining photographers who, in their long coats and fedoras, resembled a casting call for a dinner-theater production of Guys and Dolls. “When you got an assignment, this gruff guy named Krause would come back and say, ‘Hat and coat!’ ” Jack recalls. “And that was it. That was your prepping for assignments.”

Rich Cahan worked as Sun-Times picture editor from 1983 to 1996 and now, along with his partners at CityFiles Press, edits and publishes photographic histories of Chicago. He says Jack helped bring a new professionalism to Chicago photojournalism.

“There was an era of people who started as copy boys and copy clerks, then became photographers,” Cahan says. “I’m talking about the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s. Because [to be a photojournalist], you were really a good driver, you were extroverted, and you knew how to work with people. Photography was not as important as those skills. Your job was to get someplace and literally take a picture. You had an assignment, and you checked it off, and you were done. My sense of Jack is that he had a real sense of quality and purpose — that he came from a different background, where photography was art and photography was journalism. The image was really important. And not just the image, but what the image said.”

Jack confronted the entrenched attitudes of an earlier time. The Tribune required its lensmen to use medium- or large-format cameras, but Jack preferred his faster, less obtrusive 35 mm. Even after his 35 mm pictures earned front-page play, Jack clashed with management before joining the Sun-Times in 1965, as Chicago photojournalism moved into a golden era.

“The newspaper world is the world’s best taskmaster, especially Chicago during that period, with four competing newspapers — I mean, you know how competitive it was,” Jack says. “That sense of competition was there every day you went out on assignment. You were in a photo contest; you were competing against three other really talented people. Some of them were exceptionally talented, and some of them cleaned my clock. After a while, you know, I became a clock cleaner myself. But when I first started, like anybody, I was terrified. Then you grow into the business.”

In a picture of the Sun-Times’ staff, Jack points out photographer Louis Giampa. Much later in Jack’s career, he found out from Giampa’s brother that Giampa was a made man in the Chicago mob. “He was very powerful,” says Jack. “As a young photographer, I’d be photographing hoods, and one time, this guy tried to kick me. Louie was there, and he said, ‘Hey! Stand up and let him take your picture.’ ”

In addition to mob activities, Chicago was on the front lines of the domestic discord of the 1960s, both generationally and racially. Like many people his age, Jack had a political awakening and moved away from his more conservative upbringing. He photographed the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s march on Cicero, where he had the film ripped out of his camera, and went down to the South Side to help repair houses burned in an arson attack. At one rally, Jack’s reporter colleague began lecturing the segregationist mob. “He’s got a pad and pencil, and I’m there with cameras all over me when they yell, ‘Get the press!’ ” Jack recalls. “Of course, they don’t go for the guy with the pad; they go for the guy with the cameras. I had to become a sprinter for the next couple of blocks.”

Jack missed the infamous street clashes during the 1968 Democratic National Convention because he had presidential-level security clearance and was marooned inside the International Amphitheatre. “I was welded to Hubert Humphrey,” he says. “All of my friends were out in the streets, doing all of the fun stuff. Those were electric times.”

In 1970, Ralph Frost, the Sun-Times’ chief photographer, told Jack that reporters Jerome Watson and Sam Washington were investigating the inhumane conditions at a pair of psychiatric facilities after the families of residents had tipped off the newspaper. The families were especially desperate for coverage because the state was planning additional cuts to mental health funding. Washington managed to get a job as a custodian, and a school director, eager to expose the situation, gave Jack the access he needed.

A kid with Down syndrome served as a self-appointed guide, and Jack was overwhelmed by what he calls a “sensory onslaught”: a cacophony of screaming and yelling, a mix of fetid odors, and appalling scenes of suffering that have stayed with him for a lifetime. “Then the muscle memory kicked in and I began photographing,” he recalls. “It’s one of the gifts of being a journalist.”

In the best muckraking tradition of Chicago journalism, the series shocked the public, and the resulting outrage forced the state to actually increase mental health funding. Jack’s photos are revelatory and horrifying, yet they have a beauty that anticipated his later work.

“Jack sometimes underplays what he accomplished,” Cahan says. “It looks a bit like shooting fish in a barrel, because it all seems so outrageous. How could you not take a good picture? But he said it took him an hour to even figure out where he was before he regrouped, it was so bad. Then he made pictures that are so artistically beautiful. They are extraordinary.

“Some people deserve the Pulitzer Prize more than others, and Jack absolutely did. Oh, my gosh, that he was able to portray that — such a stark, black-and-white, beautiful world — was remarkable. If you look at those pictures, they’re really from someone special. I’ve never seen anything like them since. ... They’re so simple. There are so few elements. That’s what makes us able to look at them. The boldness and simplicity, and the dramatic light.”

In May 1971, while in the field, Jack received a call on the two-way radio, ordering him back to the newsroom. He was angry about leaving his assignment, then was welcomed with a standing ovation. He had won the Pulitzer Prize. He was 28 years old.

One day in 1975, high on Mount Rainier, Jack thought he was going to die.

Chuck Scott, a highly respected photo director, had lured Jack back to the Tribune and given him the chance to shoot more in-depth stories. One was about Harry Schlag, the middle-aged owner of a suburban camping store, who planned to climb the 14,411-foot stratovolcano in Washington state. Along with Schlag, Jack traveled to the Cascades with pal Bill Bendt. “We were a couple of kids from Chicago trying to do this mountain and thought we were in good shape by running around the block a couple of times,” Jack recalls. “We had no idea.”

The group attended mountaineering school and practiced for a few days prior to summiting. Schlag concluded he wasn’t up to it, but Jack and Bendt pushed on. The effort was exhausting and exhilarating — and, as Jack wrote in his book A Photographer’s Life, he never felt so alive as when “we punched through the cloud layer bathed in the crimson light.”

Then, a whiteout. The winds picked up and temperatures plunged as the jet stream slammed directly into Rainier. The group considered bivouacking in snow caves, even given the threat of avalanches, before struggling back to base camp at 10,000 feet. But their relief was brief. As the storm raged on, the guides determined that the exhausted climbers needed to continue to lower elevations.

Zero visibility has a way of bringing greater clarity. “The first thing you learn is, you learn to dig deep within yourself and trust your own abilities,” Jack says. “The No. 1 thing I learned is that I could do more than I thought I could. That self-awareness was one of the products. And actually, realizing that nature doesn’t give a shit about you was another one.”

Returning to Chicago, Jack felt estranged at the Tribune, especially as Scott’s initiatives began to encounter resistance from management. After Scott was fired, Jack turned down the position, and a sympathetic editor, recognizing the lingering impact of the Rainier episode, suggested that he take a leave of absence. With good friends living in Tucson, Jack and his wife, Margaret, drove south to spend a year in Arizona.

While Margaret worked on her master’s degree at the University of Arizona, Jack played househusband and explored the local mountains. “It was transformational, living in Arizona,” he says. “It was different then. On Thanksgiving, the mountains were covered with snow. The snow was thick, and all of the washes were running. It was just paradise.”

And the landscape appealed to his aesthetic sense. “The openness of the sky and the sweep of the light across the land is just, like, whoa!” he says. “You’re not looking through a diffuse canopy of trees; you’re seeing light transform into shapes, patterns and textures. One thing about Washington, D.C., is that the monuments are set apart. That’s what the Southwest is: The land is monumental. The sense of space and the ‘big empty.’ ”

The couple returned to Chicago for a year, but as Jack drove the expressways, there were no mountains to break the horizon. “It wasn’t a conscious thing; I just felt less complete there,” he recalls. The Dykingas relocated to Tucson in 1976, ending his Chicago newspaper career. “Jack was the premier photographer of his era,” Cahan says. “Maybe with Henry Herr Gill at the [Chicago] Daily News, he was really the most intense, serious photographer of that time.”

Jack became photo editor at the Arizona Daily Star during a time when Executive Editor Bill Woestendiek had put a new emphasis on visuals. There certainly was room for improvement. Jim Kiser, who worked as an assistant city editor and later as editorial page editor, recalls Jack’s arrival: “It was a really big deal. We were all very excited for this high-powered, very capable guy to come in. He came into a photo department where one of the people was legally blind. Which is not the best of combinations. Jack changed the department.”

Tucson lacked Chicago’s newspaper-town pedigree, but Jack ran his own show. “I left Chicago as a pretty big fish in a big pond, but it’s limited,” he says. “You’re only doing this one little cubicle of work and don’t expand to see the whole picture. In Tucson, I got to do layout, I got to do design, I watched the press run. It was a really great experience, and I enjoyed that kind of later-life growth in this industry that I knew well.”

Jack upgraded the department and explored Arizona and Mexico while working on occasional larger projects. He mentored a young, talented staff but eventually bristled at demands that were placed on the department but had nothing to do with photojournalism. Five years after taking the position, he resigned. He wanted to go back to shooting while launching a wilderness-guide business.

There were legends afoot in the Arizona of that time — writers, artists and photographers. I press Jack about Edward Abbey. “We were just occasional acquaintances, but he was very kind to me,” he says. “The best compliment was when I went over to his house and he met me at the door with this huge stack of books, basically everything he wrote, and signed them over to me. I photographed him a couple of times, and we went hiking. I wouldn’t say we were dear friends, but it’s nice to have a man like that respect you. I was a fanboy, and he was clearly an icon. … The thing that bound us together was the environment. The love for the desert.”

Back in Chicago, the work of photographer Philip Hyde — especially Hyde’s Exhibit Format Series work for the Sierra Club, advocating for the protection of such places as the Grand Canyon — had inspired Jack. “I thought, That’s real journalism,” he recalls. “I didn’t look at it as landscape photography, per se. I looked at it as doing God’s work — saving those places and saving the planet.” The two became friends after a ranger introduced Jack to Hyde at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, where the veteran photographer was traveling with his wife, Ardis, in a little Datsun pickup. After that, they ventured out together on long trips, and Hyde became a major influence.

“A lot of photographers were going to this really gonzo color transparency film, and Phil would stick to the more traditional, like Ektachrome versus some of the Fuji,” Jack says. “He would get a more nuanced, pastel range of colors. My landscape buddies were all Young Turks saying, ‘No, no, no, we have to go with this stuff.’ And I’d say, ‘Wait a minute — there’s value in looking at what Phil’s doing.’ So he gave me some grounding — not so much ‘Stand here and do this’ advice. Instead, he modeled a moral center that I needed. I think everybody can use someone like that. He was one of the most underrated photographers — if Phil had anyone hyping his work like Ansel did, he’d be right up there.”

On his first assignment for Arizona Highways, Jack worked with writer Charles Bowden, another Chicago emigrant. As Jack wrote in a 2019 tribute to Bowden in the Journal of the Southwest: “And lo and behold, up at Ramsey Canyon, I meet this abrasive, Fess Parker-looking guy. We circled each other like a couple of dogs peeing on a fire hydrant.”

They would become close friends and frequent collaborators, including on several books. Their adventures are the stuff of Southwest lore: everything from a cross-country ski journey with Arizona Governor Bruce Babbitt from Jacob Lake to the Canyon’s North Rim — before hiking from rim to rim — to a trek retracing the low-desert route of the Texas Argonauts between Yuma and Palm Springs, entirely by night to avoid the August heat. A winter canyoneering trip into Paria Canyon helped lead to the book Stone Canyons of the Colorado Plateau, which spurred the establishment of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument after the publication was given to President Bill Clinton. And, along with a group of friends that included writer Broyles and the Daily Star’s Doug Kreutz, Jack and Bowden climbed Mexico’s 18,500-foot Pico de Orizaba volcano.

Bowden was a spectacular chronicler of Arizona and the borderlands, the Abbey-in-waiting. Writers and photographers are both a natural pairing and a combustible mix, because the demands of their respective disciplines are so different. Among friends, Jack is famous for his methodical approach, but fortunately, Bowden was content to settle down in the shade and read for hours while Jack waited for the right moment. No Kindle for Bowden: He weighed down his pack with hardcovers, adding to physical challenges the two took on. On that Canyon ski trip, Jack remembers Bowden reading a big, fat book on the demise of the passenger pigeon.

As Jack wrote about Bowden, “He did what I do photographically — he became intimate with the subject through research.” Theirs was a true friendship, blending deep affection, mutual respect and occasional exasperation. Jack tells me, “Chuck had a depth of scholarship that not many writers have, because of his background as a historian. He would come up with this stuff out of nowhere — he was the equivalent of a gym rat in the library. He was also a bit of a showboat, later on. I knew him so long, I could see the change, and some of that stuff, I didn’t like. But I don’t want to go into that too far.” His voice trails off.

Jack was dying.

In 2010, he noticed his hiking abilities had declined and, fearing lung cancer, went to the doctor. Instead, he was diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. “I thought, Great!” he remembers. “It pays to be ignorant. Then I went home and looked things up and found out that in three years, I was supposed to be dead. I kind of envisioned that I would fade into the sunset, tapering off gently. I went through life blithely ignorant about how bad it was. Until it was.”

On a 2014 Canyon rafting trip, as a dust storm kicked up, Jack’s lungs stopped. “Suddenly, your eyes are wide open and you think, Shit, this is it,” he says.

It was near the end of the trip. Motoring to the takeout, Jack thought he could just go back to his hotel room and have some oxygen. Instead, he was taken to a Phoenix hospital, then to Scottsdale’s Mayo Clinic, where he was enrolled in a study for a new drug. But his lungs didn’t respond after a week of aggressive intervention. “At the end of the week,” he recalls, “they had done all that they could and said there were two options: die, or get a transplant.”

Jack was transferred to the Norton Thoracic Institute, at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center in Phoenix, for a double lung transplant and double heart bypass. The recovery was long, and Jack says Margaret was “a saint” as he battled back. Bowden was there, too, once bursting into Jack’s room without a mask or gloves. He stayed in touch with emails repeating the refrain “Johnny Cash advises lay off the whiskey and let the cocaine go,” while also proffering his lowercase wisdom:

“all the canyons will be there when you trot out of the medical caves.”

“given my little jaunts into the world, i notice there is not a lot of fair out there. so i am glad you caught a break.”

He was right about the ways of the world. A couple of months later, it was Bowden who died, of a heart attack.

Jack had lost a close friend, and nearly his own life. But, after a year’s recovery, he returned to the field with a renewed commitment. But renewed by what? “First off is passion,” he says. “Gratitude and the chance of rebirth. The chance to pay back the true heroics of the medical profession. They invested all of this in you, and you better make use of that time. I think I’m going at a faster pace than I have ever gone in my life — coupled with the ability to know what’s good and be much more selective when I actually push the shutter. Yeah, it really makes you appreciate life. And, casting out more clichés, it does make you a better person. If it doesn’t, there’s something wrong with you.”

Jack has never feared change. Although he says he once was “the digital Antichrist,” he embraced digital photography once its capabilities exceeded what he could do with film. But some things were lost. “The beauty of a 4x5 view camera is the solitude,” he says. “You pull this cloth over your head, and it’s basically you and this rectangle that’s upside-down. All of those things take you out of the normal world — being upside-down, being isolated. It’s a very Zen-like experience when you bore into that space and it becomes the canvas that you’re going to paint on. That, I miss. A camera now is a computer, and it’s going to go as fast as you can. But your task, should you choose to accept it, is to go slow.”

So, Jack slows down. He scouts and he waits, he leaves and he comes back, and he’s forever looking. Shaw, the writer and photographer, says one of his enduring memories is driving behind Jack and watching him swerve all over the road as his head swiveled from side to side, searching for scenes to photograph. In his Chevrolet Silverado with its solar panel, Jack can live off the grid, putting himself in position for those decisive moments, however far apart they turn out to be. As another friend, Spanish photographer Daniel Beltrá, puts it: “When the first rains arrive, he needs to be there. He’s very passionate about that, because the normal view of the desert is so harsh. Jack reveals the beauty that is hidden beneath the surface, that most people never get to see. He’s very attentive to be able to show those bursts of life.”

Or, as Jack puts it: “Because of the ephemeral nature of the light and the seasons and everything else, the hard part is the planning — just getting your body to that place at the right time. Then the serendipity can come in and knock your head off.”

Jack’s decades of shooting have given him an unparalleled intimacy with the land. His journalistic instincts still motivate him to tell stories, and these days, he’s rephotographing places to document how climate change has devastated the Sonoran Desert, leaving acres of flattened prickly pears and saguaros to die slow deaths over 10 years. He’s no dispassionate observer. Another good friend, Mexico City-based artist and conservationist Patricio Robles Gil, recalls a time when the two were out shooting.

“We were photographing giant saguaros, and there was a special one he wanted to show me,” Gil says. “Suddenly, he stopped and said, ‘It should be around here.’ Then he found the saguaro. It was on the ground — maybe a strong wind put it down — and he was crying. It was a very, very touching moment. You realize the kind of individual you have as a friend. I’m privileged to have his friendship.”

After meeting in Tucson, Jack and I stay in contact. While in Illinois, visiting family, he sends pictures of his grandson Nic playing baseball, and I email that old picture of Jack and his friends fishing. He makes a correction: “Btw, how the hell did you find that? I think the caption is wrong and I’m the chunky kid on the left.”

On a Sunday afternoon, I catch up with Jack as he drives west on Ina Road to photograph a family of burrowing owls. He’s positively joyful.

“Let me say the really important thing, Matt,” he says. “There are now five chicks in this burrow. They’ve been out for two days. Burrowing owls are 6 inches tall, but they punch way above their weight and think they’re eagles. They have a lot of attitude, and I have a special affinity for this group. This is the counterpoint to all the ugly stuff in life. You have to have that for yourself. It’s a refuge for the soul.”