Arizona boasts purple mountain majesties like no other, but when it comes to amber waves of grain, we’re probably not the first — or even the fifth — state that comes to mind. So here’s the shocker: Among grain gurus, Arizona is known for growing the highest-quality durum wheat in the world. Hot days, cool nights and lack of rain during the harvest period produce near-perfect wheat, dry and unspoiled by sprout damage. In 2014, according to the federal Department of Agriculture, Arizona produced nearly 8 million bushels of durum wheat; in the U.S., that trailed only North Dakota and Montana. But most of Arizona’s wheat is shipped to Italy to be turned into pasta, which partly explains why Arizona’s wheat industry has remained a secret.

You’d think Jeff Zimmerman, owner of the recently reincarnated Hayden Flour Mills, would find these statistics heartening. He’s got one of only two mills in a state that produces bushels and bushels of wheat (the state’s other mill is Bay State Milling in Tolleson). But the modern wheat varieties that farmers worldwide cultivate for their high yields hold no interest for this former North Dakota farm boy, whose family moved to Arizona in 1972.

Zimmerman saw firsthand what happened to wheat-farming and to wheat itself in the 1960s, when old-fashioned agriculture gave way to new-fashioned agribusiness. Thanks to Norman Borlaug’s “Green Revolution” (when high wheat output saved the lives of starving people in Third World countries), wheat soon became a different plant from the one our ancestors knew.

Zimmerman also witnessed how disconnected his farming friends had become from their land and their livelihood, and the impact of that stayed with him for years. His consciousness was raised even further by his wife, Maureen, a registered dietitian nutritionist and sustainability teacher who fed the family humanely raised meats and locally grown, heirloom vegetables long before “heritage” was the buzzword du jour. “We were way ahead of the curve on that one,” he says without a trace of one-upmanship. But all that healthy eating got him thinking: If people were interested in heirloom meats and vegetables, why not heritage grains?

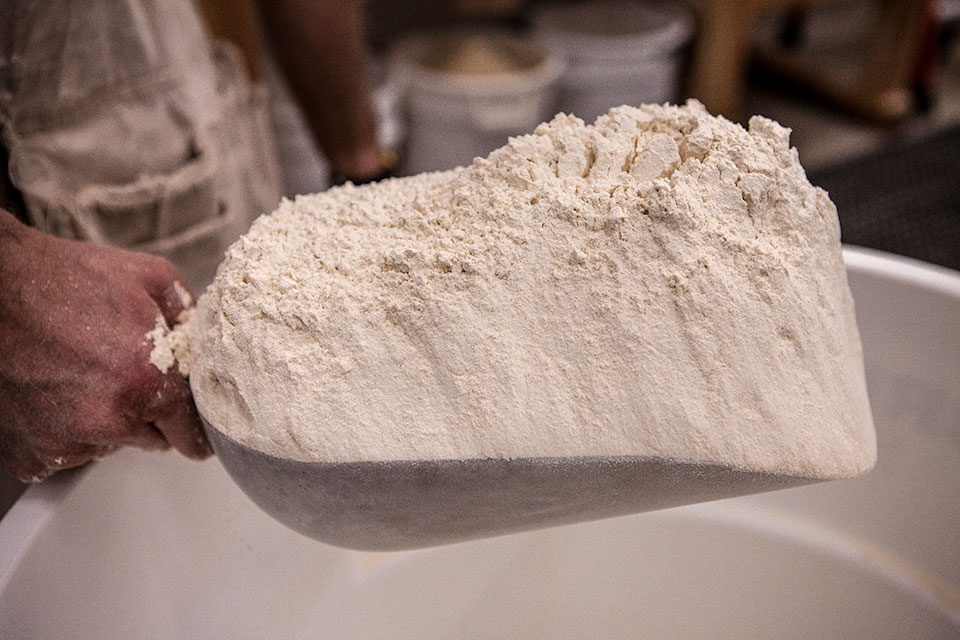

milled. | Jaques Barbey

Zimmerman now is part of a growing national movement of farmers, chefs and food artisans working not only to revive heritage grains — robust, farmer-maintained ancient varieties that do not include artificially induced genetics — but also to mill them properly, thereby retaining their flavor and nutrients instead of refining them to a fluffy, flavorless fare-thee-well. Here in Arizona, Zimmerman is the mild-mannered visionary who’s making it happen.

Like Ringo Starr, he gets by with a little help from his friends, and they’re a pretty high-powered bunch. Five years ago, when Zimmerman started asking lots of seed-related questions to anyone who might have answers, agricultural ecologist, ethnobotanist and author Gary Nabhan, who also founded Tucson’s Native Seeds/SEARCH, stepped up, putting him in touch with pioneering grain preservationist Glenn Roberts, who founded the famous Anson Mills in South Carolina. As it turned out, Roberts had been supplying flour to James Beard Award-winning pizza savant Chris Bianco (of Pizzeria Bianco and Pane Bianco in Phoenix), who had told Roberts, more times than Roberts could count, how much he lamented not being able to use local wheat for his breads and pies.

To Zimmerman and all concerned, it felt like destiny was knocking. Roberts donated thousands of pounds of heritage seeds to Native Seeds/SEARCH, which, in turn, donated 2,000 pounds of white Sonora wheat to Zimmerman’s cause. Roberts’ donation was the kick-start Zimmerman needed, and white Sonora, which represented the cultural “patrimony” Roberts had urged Zimmerman to find, made the perfect gift.

White Sonora has a rich history in the West, as Nabhan describes in The Rising of White Sonora Wheat, a 2012 article in Heirloom Gardener magazine. Introduced to the people of the Sonoran Desert in the mid-1600s by Spanish missionaries (who would use it for Holy Communion wafers), it’s a wheat with soft, blush-colored grains that make faintly sweet, wonderfully stretchy dough, perfect for tender baked goods and flour tortillas. The grain became a staple crop throughout northwestern Mexico, California and the Southwest, and remained so for hundreds of years. Enterprising Pima Indians grew it for export in the late 1800s. Although a few Native American tribes continued to dry-farm white Sonora for decades after the Gila and Salt rivers were dammed, the wheat’s heyday was over by the 1930s. By the time Zimmerman was nurturing his seedling of an idea, white Sonora had been forgotten by all but a handful of food historians and preservationists.

Scoring the seeds of what was once the region’s most popular wheat was a coup, but then Zimmerman had to find farmers willing to grow what must have seemed too precious a product for a boutique market. Steve Sossaman, whose great-grandparents started farming in Queen Creek in 1919, was the first farmer Zimmerman says was “crazy enough to do it.” In 2011, Sossaman planted 30 of his 800 acres in white Sonora, red fife and emmer farro, reserving the rest for cattle feed he’d been growing for decades.

The seeds were in the ground, and Zimmerman would soon be ready to use his traditional stone mill. It was imported from Austria, one of a handful of European countries where both milling and baking are small-batch traditions. For those of us who are Arizona bred and buttered, it’s hard to imagine that Zimmerman’s 1,600-pound wooden mill could easily fit into someone’s living room. We can’t shake the image of the Hayden Flour Mill (circa 1918). Made of reinforced concrete, it still sits on Mill Avenue at downtown Tempe’s northern edge. But it is not the original, river-powered mill founded by Charles Trumbull Hayden in 1874; that mill was lost to fire 20 years later. Nor is it the second, adobe incarnation, which burned to the ground in 1917. The grain elevator and massive silos that stand east of the mill we see today were built in 1951, and despite the name, they have far less to do with Hayden than they do with modern-day industrial milling.

Nevertheless, Zimmerman jumped at the chance to buy the Hayden Flour Mill name, which represented Arizona’s agricultural history so well. It became available when, after a 17-year-run, Bay State Milling ceased operations at the original mill site in 1998. Zimmerman’s extensive research told him that Hayden — the co-founder of Tempe, and the father of Arizona’s beloved Senator Carl Hayden — was a kindhearted businessman who brought the community together through the mill. He was the sort of guy who somehow misplaced his ledger after a devastating flood, thereby wiping clean the debt his customers and friends would have been hard put to repay.

Zimmerman liked these stories. He liked thinking about bringing a modern community together in much the same way that Hayden had. He also thought it might be worthwhile to educate the public about flour and encourage people to think as Europeans do: that freshness and quality take precedence over price. In 2011, Bianco, a kindred spirit, offered Zimmerman space for his mill in the backroom of Pane Bianco, and Hayden Flour Mills was reborn.

Five years later, more than 15 Arizona farms have jumped on Zimmerman’s not-so-zany bandwagon by growing nearly a dozen different heritage grains, including barley, rye and Chapalote corn. Local restaurants such as Crudo, Essence Bakery Café, FnB, Gertrude’s, Otro, Southern Rail and Tarbell’s buy milled grain from Hayden Flour Mills, as do dozens of restaurants elsewhere in the state and as far away as Pennsylvania, Texas and New York.

Zimmerman and his crew — which includes his daughter Emma, who manages day-to-day operations, and his meticulous miller, Ben Butler — have recently moved operations to a renovated pole barn at Sossaman Farms in Queen Creek. Ever the idea guy, Zimmerman has big plans for the sparkling space, including solar-power installation.

In the years to come, Zimmerman and Sossaman envision what they call a “heritage corner,” where grain-oriented operations such as a bakery and a brewery might open on the property. Down the road, Zimmerman says, “the old hippie guys will move on, letting the millennials carry this forward.” He’s referring to Emma, Ben and Sossaman’s two daughters, Taylor Tolmachoff and Caroline Sossaman, who also are involved with the mill.

At the moment, however, Zimmerman busies himself with a new product line: Hayden Flour Mills wheat crackers made with white Sonora, red fife, blue beard durum and farro. Zimmerman likes the tagline “Taste the Grain,” which seems to fit for a guy who has already proved that going against the grain often has its sweet reward.

Hayden Flour Mills is located at 22100 S. Sossaman Road in Queen Creek. For more information, call 480-557-0031 or visit www.haydenflourmills.com.