To tell the story of artist and photographer Kate Thomson Cory, you start in the middle, not at the beginning.

In 1905, Cory was 44, less than halfway through what would turn out to be a long, long life. Small and wiry, with piercing blue eyes and a prominent nose that commanded a pale, serious face, Cory was an accomplished artist in the New York scene and was in her creative prime. She was unmarried — a spinster, in the parlance of the day.

Cory worked as an instructor at Cooper Union, a private college in Manhattan, and shared a flat overlooking Central Park with writer Maude Banks. The two belonged to Pen and Brush, an organization whose membership one newspaper described as “the cleverest among New York women writers and painters.” Cory would later say that Banks “was a pen and I was a brush,” and the two friends “were keyed to city life from disposal of garbage to Grand Opera.”

Then, she left it all behind.

In an unpublished account, Cory recalled the day she and Banks ran into acclaimed Arizona painter Louis Akin at a newsstand. A prominent Fifth Avenue gallery was showcasing his Grand Canyon paintings in a major exhibition, and Akin rhapsodized about the Arizona Territory’s landscape and the Hopi people. He told the women he planned to start an artists’ colony on the Hopi mesas and invited them to join what he envisioned as a Southwestern counterpart to Pen and Brush.

Lives change, sometimes quickly: In September 1905, Cory stepped off a Santa Fe Railway train at Canyon Diablo, midway between Winslow and Flagstaff. She was the only passenger to get off at this remote Painted Desert stop; in fact, the porter told Cory he hadn’t seen any passengers disembark at the station for two years.

Cory looked out onto what she described as a “land of space and horizon — and apparently nothing else.” But she never used her return ticket. For the next 53 years, Arizona became her focus as she created an incomparable photographic record of the Hopi people and a collection of paintings that captured the state’s landscapes and cultures. She wrote: “Fate, or the pioneer blood within me, with the able assistance of the Santa Fe, had picked me up, without my realizing the abyss I was leaping, and was carrying me into another existence.”

Kate Cory was home.

Raised in Waukegan, Illinois, near Chicago, Cory grew up in a prominent family. Her mother’s side arrived in North Americain the 1600s, and her maternal grandfather was a Harvard-educated doctor. A native of Canada, Cory’s father, James, served as editor of the Waukegan Weekly Gazette and city postmaster. He was a staunch abolitionist involved with the Underground Railroad and counted Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant among his friends. The two future presidents even stayed and dined at the Cory home.

Cory had an independent spirit and didn’t readily submit to the niceties. In her book Confessions of a Tomboy, she wrote, “Somehow in Nature’s great workshop some gadget or gadgets that were meant for boys got into the girl’s department and into the here and there makeup of a few otherwise normal feminine embryos, and many a breach of conduct is the result — if you’re looking for perfect ladies.”

When her father became a stockbroker in New York,

Cory moved there to study art, then lived in Manhattan for 25 years before trading the apartment building Akin likened to an urban cliff dwelling for two tiny rooms at Oraibi, on Third Mesa.

Arizona both overwhelmed and inspired Cory. Looking out at the terrain, she worried she had packed too much green and not enough red and blue in her paint box. She also recalled that “I was ready to go anywhere and see everything.”

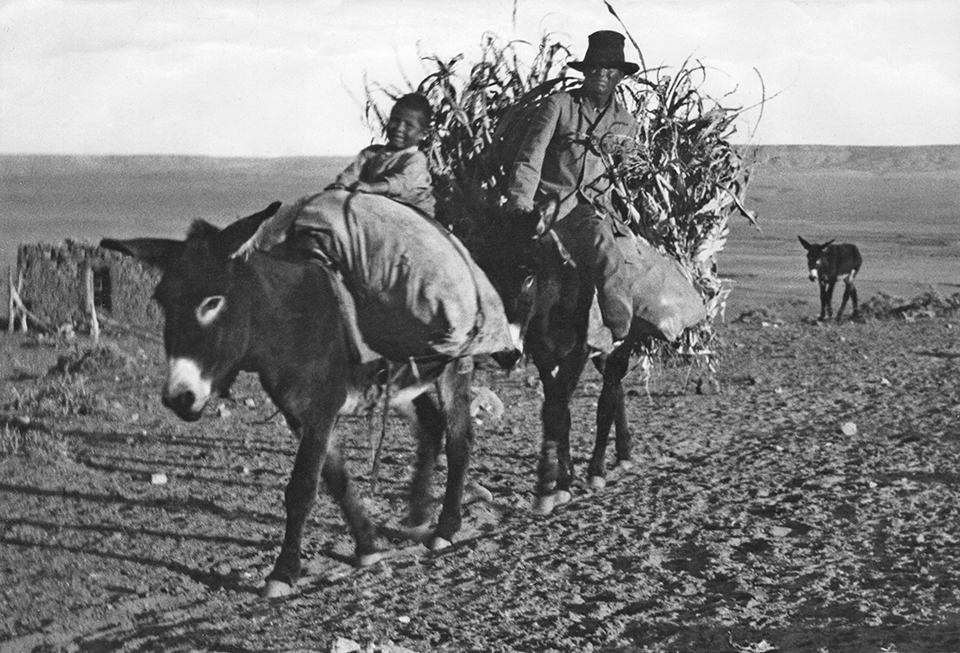

The afternoon she arrived, Cory saddled up Old Roney, a gentle stallion, and took the first horseback ride of her life. She visited an encampment in a nearby canyon, where she watched Navajos roasting corn over an open fire. The next morning, shaded by an umbrella and riding in a buckboard, she set out with a Canyon Diablo trader to deliver lumber to 560-foot-deep Meteor Crater (“It must have been a mighty thud,” she wrote). Then, the wagons doubled back to Canyon Diablo for the two-day journey by prairie schooner to Oraibi.

Those 70 miles were the most arduous of Cory’s transcontinental journey. Her references to “the ports” of Winslow and Holbrook and of “the trip inland to Oraibi” hint at her perceptions of the desert’s oceanic scale. The trip took on a surreal quality, too: “There were mirages, lakes ahead to which we never came, and ghostly whirlwinds spinning along in the distance, curling white alkali dust to the heavens.”

That night, Cory awakened with a start, dreaming that an eagle was about to seize her in its talons and carry her back to her flat high above Central Park.

In Arizona, Cory quickly realized that Akin’s grandest ambitions would never come to pass. As she later put it, “I was ‘the colony.’ ”

She decided to live among the Hopis and found a tiny apartment, filled a foot deep by the previous season’s harvest of yellow and blue corn. The ceiling was so low that even the diminutive Cory stooped to avoid bumping her head. The passage between rooms was barely 3 feet high. But she wrote that the apartment sat on “the top story, the highest in the village, whose roof commanded an almost unbroken view of the entire horizon, and as the village itself is five or six hundred feet above the desert, my outlook was a commanding one.”

According to Marc Gaede — who in 1986 co-authored The Hopi Photographs: Kate Cory 1905-1912 with his wife, Marnie, and Hopi authority Barton Wright — Cory used a large-format 4x5 camera, mostly hand-held, and tried to balance her need for fast film to capture movement with overall image quality. Conditions were far from ideal: Cory strained drowned mice, rats and insects from the water she collected for the development process.

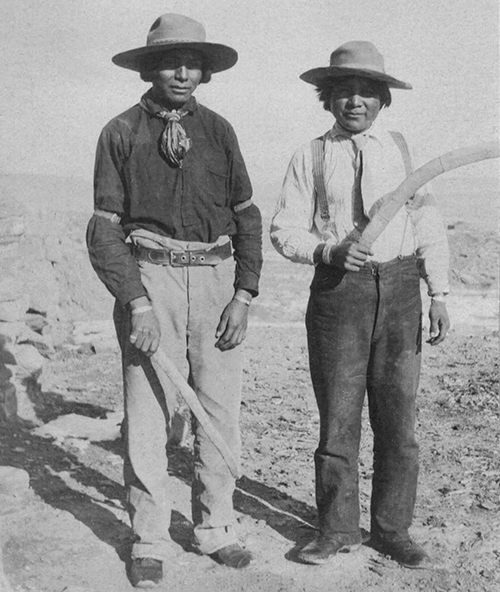

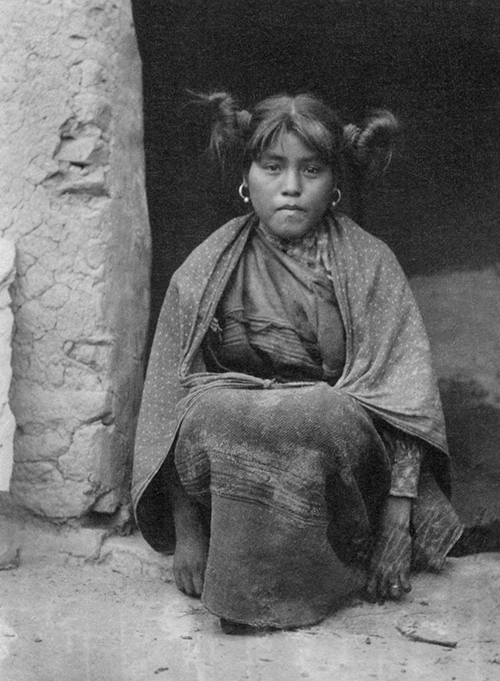

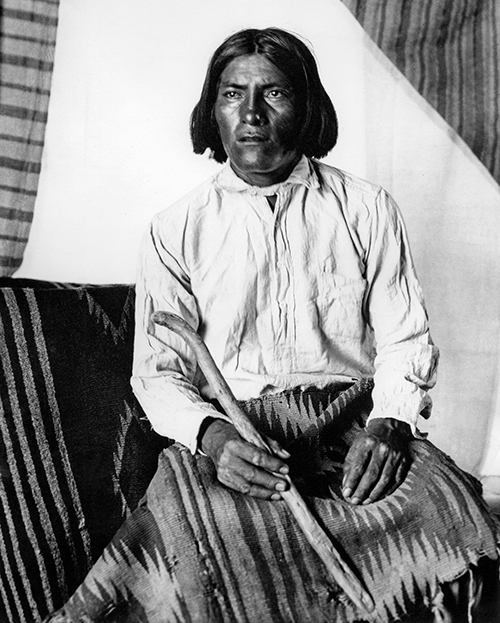

Celebrated photographers, Edward S. Curtis and Adam Clark Vroman among them, documented the Hopi people. But Cory’s photos of daily life have an immediacy that stands out from her counterparts’ stylized images. “We took the photographs to Ansel Adams,” Gaede recalls. “He loved the images. And he said some of the head-and-shoulder shots reminded him of the early work of Dorothea Lange.”

If people in vintage photographs typically look uncomfortable, Cory’s subjects, dressed in their own clothing and going about daily routines, appear natural, probably because Cory had become part of their world. She

taught at a school and compiled a glossary of more than 900 Hopi words. She was invited into sacred, all-male kivas, which was rare for outsiders, particularly women. The Hopis dubbed her Paina Wurti, or “Painter Woman.”

“They were fascinated by her,” Marnie Gaede says. “Had she had some big ego, she wouldn’t have lasted a week. But Kate, I think she diminished herself and was very respectful. It’s also a matrilineal, matrilocal, matriarchal society, so she was halfway in the door because she was a woman. That’s what makes it a good modern story. This was a woman who went out there in 1905 from Cooper Union and got on a train and just did it. That’s extraordinary considering what people thought a woman should or shouldn’t do back then. She didn’t try to convert anyone. She was there to observe them respectfully.”

Cory lived on the mesas during a time when the outside world was increasingly closing in on the Hopi people. She describes crowds of “expectant tourists: scientist, globe-trotter, soldier, pretty girl and ample matron, and the grandly superior who has seen it before and will tell you all about it.” The visitors massed along rooftops and took prime spots to witness such rituals as the Corn Dance. Even with these intrusions, Cory lost herself in a way of life vastly different from the one she left more than 2,000 miles away in Manhattan.

“In their midst,” she wrote, “one feels transported to another age, and the busy world outside becomes vague and remote, the home letters are echoes from a place we used to be familiar with, and the world news at large almost as if it comes from another planet.”

In a January 1910 letter, Cory outlined her desire to move to Prescott and live in a stone Hopi-style structure. Her letters offer a glimpse of her busy, restless mind, with precise, if rushed, handwriting that continues around the margins so she could complete her thoughts after reaching the bottom of the page.

By 1912, Cory had moved into a house built by Hopi craftsmen in Prescott’s Idylwild tract. She became a notable local resident for both her artwork and her eccentric ways. Her painting Arizona Desert was displayed and sold in 1913 at the Armory Show, the famous New York exhibition that brought works by the likes of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso to the U.S. And given her ragged clothes and cluttered, simple household where she cooked cans of beans over a wood-fired stove, some thought Cory lived more like a Hopi than like a proper woman of Prescott.

But Cory was also close friends with historian and poet Sharlot Hall (and is buried next to her in the Arizona Pioneers’ Home Cemetery), and she became involved with the Smoki People, the group of prominent local men that at one time included Barry Goldwater. Despite the Smokis’ all-white membership, Hall crafted a mythology for the group as a vanishing race, and the group’s stated mission was to perpetuate disappearing American Indian traditions.

Cory worked with the Smokis to ensure the authenticity of the costumes and choreography as the members, their bodies painted brown, re-created sacred dances for thousands of tourists and Prescott locals. She also helped design the Hopi-style Smoki Museum (renamed the Museum of Indigenous Peoples in 2020), which still displays several significant Cory paintings. Cory’s The Migration depicts the banishment of a group of Hopi traditionalists from Oraibi after a violent clash she had witnessed and photographed.

Although the Smokis claimed the dances were a respectful tribute, formal Hopi opposition led to the cessation of the performances in 1990. Those objections weren’t anything new, and the question arises of whether Cory, even during a very different era, should have been more protective of sacred Hopi rituals. As far back as 1924, a Los Angeles Times article called the dances “a thoroughly offensive, objectionable and indefensible” burlesque. Hall responded, “The dances and the ceremonials are directed down to the smallest detail by Miss Kate Cory, an artist whose works rank with foremost names of California and the East; and whose many years of residence and intimate study in the Hopi villages have made her an authority recognized by the United States government and the leading ethnologists.”

Cory’s photographs, even though she made them years before the Hopis banned photography in their villages to protect the sanctity of their rituals, have also inspired debate. And those photos almost didn’t survive: Nearly three decades after Cory’s death in 1958, more than 600 negatives were discovered haphazardly stored in a shoebox at the Smoki Museum. Many of the highly flammable nitrocellulose negatives had no protective sleeves, and some were disintegrating before they were transferred to the Museum of Northern Arizona for preservation.

Marc Gaede had worked as the museum’s curator of photography and ultimately received publication rights. In that pre-digital time, some individual negatives required weeks of restoration, and 68 pictures were ultimately included in The Hopi Photographs. “This collection, taken at the time period they were by Kate Cory, makes it, in our opinion, the most important photographic documentation of any American Indigenous tribe,” Gaede says. “Anywhere — South America and North America.”

Cory never displayed or sold her pictures, and it’s assumed she intended to use them as a basis for her paintings. Even now, anyone wishing to view the more sensitive images must receive permission from the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office. When the Gaedes created the book, that office didn’t exist, but Marc Gaede says he consulted with prominent Hopis.

“I was never told by anyone, not one, not to print those photographs because of cultural purposes,” he says. “Now, I’ve had competition from other anthropologists who disputed what we were doing with the book. But never did a Hopi tell me not to do the book. And they certainly knew about it.” That said, the Gaedes have no plans for another book printing and acknowledge the project would never receive permission today.

All of this speaks to the uniqueness of Cory’s art. At 78, Cory was asked whether she intended to slow down. “Indeed not,” she replied. “Life is just beginning.” She was right: Cory lived for another 20 years, and her legacy has gained a complicated and controversial half-life. And if the story of a life doesn’t always start at the beginning, it doesn’t always end with death. Because Kate Cory, the contemporary woman of early 20th century New York, is still relevant nearly 120 years after she bade farewell to the modern to discover the timeless.