Editor’s Note: In the coming months, we’ll be releasing Indigenous Arizona: The Portraits. The book will feature some of the best Native portraits from the archive of Arizona Highways. What follows is a selection of those images.

Arizona captivates most visitors with its unparalleled natural beauty and vast array of cultural diversity. In recent times, Arizona has become the catalyst for photographers of all kinds to converge in search of new and exciting subjects.

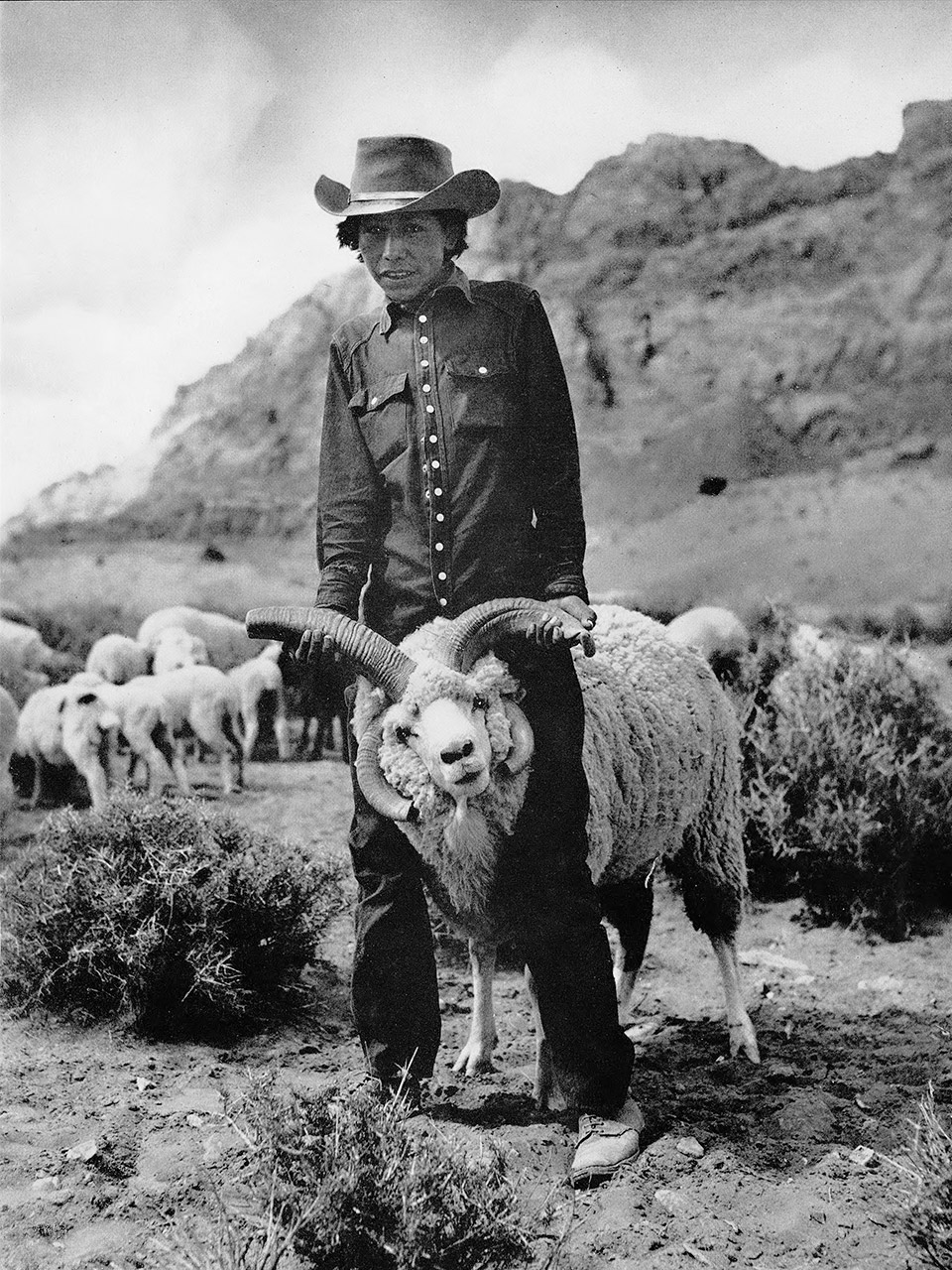

The stunning variety of traditional Native American culture and Western frontier heritage blends perfectly within the different landscapes, which inspire photographers and artists to come and explore the grandeur of the American Southwest. Environmental portraits from years past are one of the most important forms of visual records available for the preservation and study of Indigenous cultures. The members of the diverse tribal cultures in Arizona are often defined through photography.

Arizona Highways’ contributing photographers, along with historians, have painstakingly worked to preserve this important photographic record of Indigenous families — their rich cultural traditions, customs and ways of life — in Arizona. Through their combined efforts, much of the original material that hasn’t survived has been reproduced here so that we may all continue to appreciate those works of art by the dedicated photographers working with their subjects.

Indigenous Arizona: The Portraits is a book that focuses on and celebrates the work of Western photographers who documented Native American tribal gatherings, traditions and daily life. These brave individuals produced beautiful images that have become iconic and instantly recognizable, including work by Ansel Adams, Josef Muench and Jerry Jacka — just to name a few.

Indigenous Portraits is also a dream come true for me as a photographer. Making a portrait is every photographer’s dream — mine especially, because, as an Indigenous photographer, I’ve had the privilege to work with some of the most revered tribal members in my home state. They all have their own stories, stories that go to depths beyond the photography — and that nudged me even closer and deeper into their lives. Every time

I left their presence, I felt so rich with experience.

History has shown that when a photographer travels into Dinétah, the land of the Navajos, with their cameras, Navajos generally respond with shyness. As a Navajo (Diné) photographer, I am no exception to this rule. At times, I have been met with the same reluctance by my Navajo subjects. However, underneath this veil of shyness lies an image that I know exists, one with which most Native Americans are familiar — one that transcends language and culture, one that we all share.

Diné portraits are the most dramatic, complex form of portraiture I do. I capture my subjects wearing centuries-old finery in their finest moments, telling a story that tells who they are and where they come from. My work celebrates my subjects’ connection to the past, while still celebrating them within today’s urban world. The portraits in this book reflect Indigenous people from a variety of tribes as they truly see themselves, through the lens of documentary photographers who can see even more than what you see looking at their work today.

LeRoy DeJolie is a member of the Navajo (Diné) Nation and resides in Kaibeto, Arizona. His matriarchal clan is of the Big Water Clan (Totsohnii) and born for the Redhouse Clan (Kinlichinii). His work is inspired by the vast and beautiful landscape of Arizona. “I grew up in this region and have always been fascinated by its natural beauty, as well as the people who inhabit it,” he says.