Red Butte rises from the tablelands of the Coconino Plateau like a camel’s back. The formation’s unmistakable hump, which juts more than 800 feet above a sea of golden prairies, is capped with bands of rust-colored sandstone that radiates orange in the late-afternoon light. The butte is a beacon for Northern Arizona travelers, signaling that the South Rim of the Grand Canyon is near.

But for Indigenous tribes with long-held cultural and spiritual connections to the Grand Canyon, Red Butte is much more than a landmark. “This is our home,” says Havasupai Tribe elder and medicine woman Dianna Sue White Dove Uqualla. “We came from here.”

Located a few miles south of Tusayan and just off U.S. Route 180, Red Butte is known to the Havasupai people as Wii’i Gdwiisa, which means “clenched fist mountain.” It is their place of emergence, where life began for the tribe. Yet Red Butte receives barely a passing glance from many travelers as they zoom along the highway, eager to reach Grand Canyon National Park and feast their eyes on one of the world’s most famous natural wonders.

Uqualla, three of her family members and several other Havasupai have generously offered to introduce me to Wii’i Gdwiisa as part of their ongoing effort to protect it. While their ancestors experienced abuse in boarding schools for practicing their traditions — and consequently believed it was best to keep quiet about spiritual connections to the land — today’s Havasupai are now speaking up.

“All you see are trees and dirt, and it doesn’t mean anything to you,” Uqualla says of how she’s tried to explain the significance of Red Butte to non-Natives. “But it means a whole lot to us. We once lived all around here, and we used the plants as medicine.”

It’s late May, and we’re huddled in the shade of a piñon pine to escape the afternoon heat. Uqualla says that before they were driven onto federally designated tribal lands and Red Butte became part of a national forest, Indigenous people gathered piñon nuts here and used the pine’s sap for its healing properties. “This land is a living entity,” adds Stuart Chavez, another Havasupai tribal member. “And right now, as we hear the wind moving through the trees, that is our ancestors acknowledging our presence.”

Red Butte towers in the sun, across a field of yellow grass where Uqualla’s grandchildren are adjusting their traditional clothing ahead of a blessing ceremony. Chavez points to the base of the butte and says a historic Havasupai sweat lodge site is located there, in the trees. A sacred spring that sustained the tribe centuries ago is also nearby.

Called Havasuw ’Baaja, “the people of blue-green waters,” the Havasupai are best known for their tribal land and spectacular waterfalls in Havasu Canyon, the Grand Canyon tributary where tribal members currently live. But their traditional homelands extend far beyond the bottom of the canyon.

According to the Havasupai and other tribes, the Grand Canyon occupies an area much bigger than the expanse between its two rims. It’s a sprawling landscape marked not by government boundaries but by an interconnected web of humans and animals, water flowing above and below ground, respect for ancestors and obligations to future generations. This interconnectedness is like a tightly woven basket made up of countless fibers that contribute to the strength of the whole. For American Indians, the chasm of the Grand Canyon is intrinsically tied to the plateaus surrounding it and the Indigenous peoples who have been stewards of the land for thousands of years.

That view was not shared by most of the European colonizers who settled North America. Beginning with Yellowstone in 1872, the federal government set aside places with jaw-dropping scenery as national parks. And sites deemed important by non-Native scientists and archaeologists were preserved as national monuments, while areas such as Red Butte were left open to resource development as Indigenous spiritual connections to the land were dismissed.

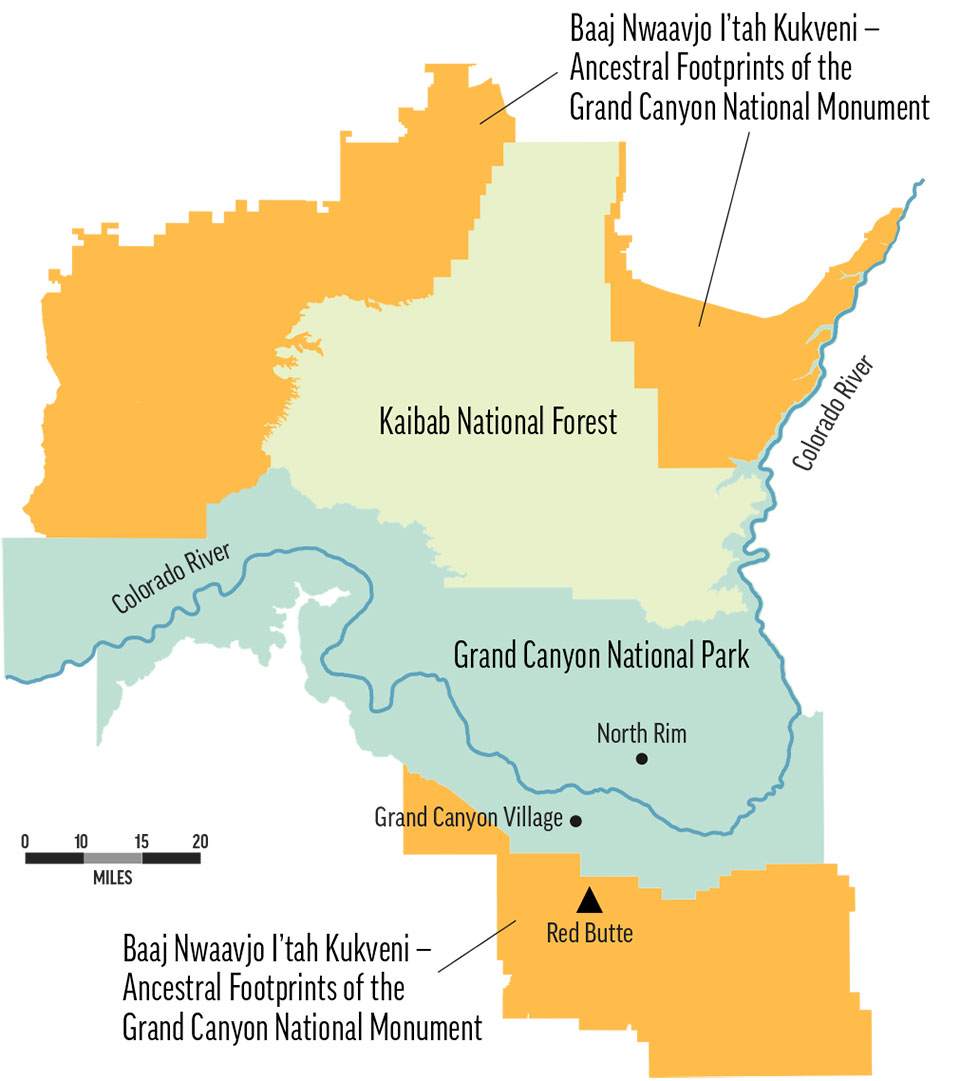

But that history was turned on its head in August 2023, when President Joe Biden designated the 917,618-acre Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni — Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument. The first two words of the monument’s name are Havasupai, meaning “where our ancestors roam”; the third and fourth words are Hopi, reflecting a similar sentiment that translates to “our ancestral footprints.”

below. | John Burcham

The monument encompasses the entire Canyon watershed and abuts the northern and southern boundaries of Grand Canyon National Park. Above ground are coniferous forests, vast grasslands, piñon-juniper plains, and countless creeks and springs that flow into the Colorado River like veins carrying blood to a heart. Below the surface are aquifers, including the massive Redwall-Muav Aquifer (or R Aquifer), that form a hidden world of interconnected channels storing a mother lode of ancient snowmelt from the most recent ice age. The R Aquifer nurtures ecological oases inside Grand Canyon National Park, where this “fossil water” bursts from canyon walls to create Roaring Springs, Tapeats Spring, the Thunder River, Vasey’s Paradise and dozens of other water sources. It’s also the source for Havasu Creek, which feeds Havasu Falls and provides drinking water to the Havasupai Tribe.

Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni is the culmination of a decadeslong effort by environmental and Indigenous groups who have insisted the entire Canyon watershed must be protected from development to preserve the crown jewel at its heart. But the final and definitive push for the monument came from a coalition of 13 tribes with deep ties to the Canyon: the Havasupai Tribe, Hopi Tribe, Hualapai Tribe, Navajo Nation, Pueblo of Zuni, Yavapai-Apache Nation, Kaibab-Paiute Tribe, Las Vegas Paiute Tribe, Moapa Band of Paiutes, Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, Shivwits Band of Paiutes, San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe and Colorado River Indian Tribes. The group formed after the president was elected in 2020, and over the past several years, it has aggressively lobbied the White House and Arizona’s members of Congress for protection of the tribes’ homeland.

Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni is the 19th national monument in Arizona, which has more such monuments than any other state. Yet, as the non-English name reflects, the monument is unlike any other. Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni is one of the first national monuments in the country to be charged with honoring tribal values and restoring Indigenous connections to dispossessed homelands. Red Butte is protected within the new preserve, as are numerous springs, thousands of archaeological sites and places where Indigenous ancestors are buried. The monument also prevents new mining claims for uranium and other minerals, a critical concern for environmental and tribal groups.

While the monument designation was a huge victory for the 13 tribes that came together as the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition, it does not mean their fight is over. The current challenge for the Havasupai and other tribes is to help non-Native people appreciate why the monument was created and embrace the idea that protecting the Canyon requires preserving the lands surrounding the crown jewel, as well as the Indigenous cultures that have called the area home for thousands of years.

“People have a hard time understanding that we belong to the land and the land belongs to us,” says Matthew Putesoy, who serves with Uqualla and Chavez on a Havasupai committee leading the protest against uranium mining. When Biden was considering the monument designation in the summer of 2023, the committee was asked to send the White House information about the tribe’s story of emergence at Red Butte.

“It is difficult to convey this connection to politicians who always want to make economic development their No. 1 priority,” Putesoy says. “But my grandfather told me, ‘Just keep telling our story over and over, and maybe one day somebody will listen.’ ”

According to Putesoy, the complete Havasupai origin story exists only in oral form, and sharing it in its entirety would take about four days. Various tribal elders are keepers of sections of the story, and responsibility for preserving the information is passed down through generations, as Putesoy’s grandfather and uncle did for him.

The traditional homeland of the Havasupai encompasses most of the Grand Canyon, as well as hundreds of square miles of upland plateaus south of the gorge. Part of the tribe’s origin story includes instructions from the creator to be both farmers and hunters, living along streams in the summer to grow crops and on the plateaus in the winter to hunt big game.

“The non-Indian descriptions of [the Havasupai] as a canyon-dwelling people miss the essential character of the Havasupai, who conceive of themselves as a people of space,” writes Stephen Hirst in his book I Am the Grand Canyon.

The Havasupai world shrank dramatically in 1880, when the tribe was allotted a Havasu Canyon reservation of a mere 518 acres, the smallest in the United States at the time. Although they were ordered to stay in the canyon, tribal members continued to migrate to their winter homes on the plateau to sustain their families. But in 1893, the U.S. government created the 1.8 million-acre Grand Canyon Forest Reserve (now part of the Kaibab National Forest) and banned the tribe from hunting or living anywhere on the Coconino Plateau.

“The Grand Canyon of the Colorado River is becoming so renowned for its wonderful and extensive natural gorge scenery and for its open and clean pine woods that it should be preserved for the everlasting pleasure and instruction of our intelligent citizens as well as those of foreign countries,” wrote regional forest supervisor W.P. Herman to his superiors in 1898. “Henceforth, I deem it just and necessary to keep the wild and unappreciable Indian from off the Reservation and protect the game.” To achieve this, Herman instituted regulations that made it illegal for the Havasupai not only to hunt on the plateau, but to set foot on the forest reserve for any purpose.

The final blow came in 1919, when Grand Canyon National Park was established and the Havasupai were evicted from sites along springs where they had farmed for 1,000 years or more. Several years before the park dedication, President Theodore Roosevelt visited the Canyon and rode a mule down the Bright Angel Trail. He stopped at what settlers called Indian Garden (recently renamed Havasupai Gardens) and, with much fanfare, personally informed Havasupai families that they would need to move out to make way for the park.

Meanwhile, the tribe’s home on the South Rim, inside what had become the national park’s Grand Canyon Village, was deemed an eyesore to tourists. Traditional brush shelters called wickiups were burned to the ground with Havasupai possessions still inside. According to Hirst, anyone living at what then was called Supai Camp and not working in the park was ordered to leave. The National Park Service drove a group of mostly women, children and elderly tribal members to Topocoba Hilltop, west of the village, and told them to hike 14 miles and down 2,300 feet to their land in Havasu Canyon. It was winter, and the trail was covered with snow. “Those abandoned at Topocoba were too tough to freeze,” Hirst writes. “They were also too angry to forget.”

The presidential proclamation designating Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni openly recognizes the harms caused by the federal government to the Indigenous peoples of the Canyon. This view is echoed by the leadership of the Kaibab National Forest, which manages the national monument along with the Bureau of Land Management. The agencies have pledged to involve tribes in a “co-stewardship” model to better protect their homelands.

“It is important to acknowledge the history of the United States and its treatment of tribal nations,” says Nicole Branton, the Kaibab National Forest’s supervisor, in an email. “Lands within the monument are places where Indigenous people were forced out, creating devastating impacts to traditional cultural and religious practices. The Forest Service is committed to an agency-wide strategy to co-steward with tribes in a manner that recognizes and honors tribal treaties … and [greatly expands the] scope and scale of tribal involvement in agency work, planning and decision-making, as well as tribal self-determination.”

Branton adds that the national forest is helping to form a commission, composed of tribal representatives, that will start working with the agencies on a monument management plan by the end of 2024 so that the agencies can “begin figuring out what shared stewardship with tribal nations looks like.”

Implementing these goals is easier said than done. Other federal land management policies still in place are at odds with protecting tribal cultural values. For example, even though the monument prevents new mining claims within its boundaries, the federal Mining Law of 1872 required the Forest Service to grandfather in mining operations with “valid and pre-existing rights.” Consequently, the Pinyon Plain Mine (formerly the Canyon Mine), 3 miles north of Red Butte and 7 miles from Grand Canyon National Park, began extracting uranium ore this past January, to the dismay of tribes and environmental groups.

Energy Fuels Inc., the owner of the mine, states on its website that Pinyon Plain uses “state-of-the-art environmental controls and groundwater protections.” The company also says the mine is in full compliance with state and federal mining safety regulations, and that Pinyon Plain will create 60 local jobs. But the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition, along with environmental groups and some scientists, argues that if the mine has an accident, the irreversible consequences of uranium contamination in the R Aquifer and the Canyon’s springs will overshadow any economic benefit from the operation.

The Havasupai fear the loss of their only source of drinking water and the deadly health effects of uranium contamination. But they also fear the spiritual consequences of what Pinyon Plain is doing to the Canyon, with its 1,400-foot mine shaft drilled into an ancient aquifer, an open-air holding pond containing radioactive wastewater, and freshly extracted uranium ore stored on the ground before being trucked across the Navajo Nation to a mill in Southeastern Utah.

As we gather at the foot of Red Butte, Uqualla’s 15-year-old grandson, Kristopher Siyuja, has been thinking about his ancestors and what they endured. “When I stand at the edge of Grand Canyon, I can feel them standing next to me,” he says. “I want to tell the park visitors around me that we are the original people of this land.”

Kristopher and his sister, Audra Jones, 11, live with Uqualla in the national park, at the small community of Supai Camp — where their ancestors were driven out decades ago. The Park Service restored the area in 2010 with modern housing and now welcomes Havasupai Tribe members. Kristopher and Audra say they like living there and going to school in the park. Kristopher’s cousin Kambria Siyuja is attending Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado; she also carries the honor of representing the tribe as Miss Havasupai.

Uqualla is teaching her family members the Havasupai language and other aspects of their culture, including ceremonies, dances and how to gather medicinal plants. But she says they recently stopped gathering plants around Red Butte, fearing airborne contamination from the mine.

With Red Butte towering nearby, Kristopher, Audra and Kambria kneel in a meadow while Uqualla says a prayer in Havasupai. Fragrant smoke from a bundle of burning sage spirals up from the center of the prayer circle. Uqualla explains in English that she has asked the creator to make the children strong and to give them permission to “stand up” for their homeland.

Kristopher, Audra and Kambria are clearly proud of their culture and the fact that a new national monument recognizes the Havasupai origin place. “I am glad my grandmother is teaching me these things so when we are older, we can follow in her footsteps,” Kristopher says.

He’s also proud that he helped represent his tribe when the president sat at the base of Wii’i Gdwiisa on August 8, 2023, and signed the proclamation creating Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni. Kristopher and Audra performed a traditional dance as part of the ceremony. “This made Red Butte happy,” Uqualla says.

“They danced with respect and honored the song,” she adds. “Because they are young, it was rejuvenating to the land, a blessing to the ground.”