ARIZONA’S MIDRIFF IS FAR FROM BARE. If you scurry across the much-used southern routes, you may think we haven’t enough wood to make a totem pole. But that’s because you’ve bypassed our 11-million-acre vacationland — our national for-

ests. With more than a hundred species of trees, these stretch from the “Strip” north of the Grand Canyon to the south and to the east.

One tree, the ponderosa pine, grows in a single, continuous stand nearly 300 miles long, from 20 to 60 miles wide, from north of the Grand Canyon well into New Mexico, through the northern and central part of the state. It grows at a higher elevation. Our state tree, the filmy palo verde, prefers the washes of the deserts.

The old Crook National Forest, named for that intrepid General George who ended the Indian Wars with the respect of Indians, has been gobbled up by other national forests. But we’re still left with all of six, and part of two, within the state’s borders. Their roll call sounds our history.

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado’s expedition of 1540 is suitably commemorated by the only national forest touching Mexico’s border. Its 1,386,000 acres are scattered in disconnected areas from Rodeo, New Mexico, to Tucson, including Douglas, Patagonia and Nogales. Zane Grey immortalized the Tonto. The Sitgreaves was named for Captain Lorenzo. The Prescott National Forest reminds us of our first state capital. Add the Coconino (“piñon nut people”), the Kaibab (habitat of the peculiarly charming Kaibab squirrel), the Apache (mostly in New Mexico) and the Gila (with Silver City, New Mexico, as headquarters), and you have Arizona’s history — and her forests.

In one of them, at every season of the year, there is the ideal vacation and recreation for everyone who seeks the land of

room enough, and space enough.

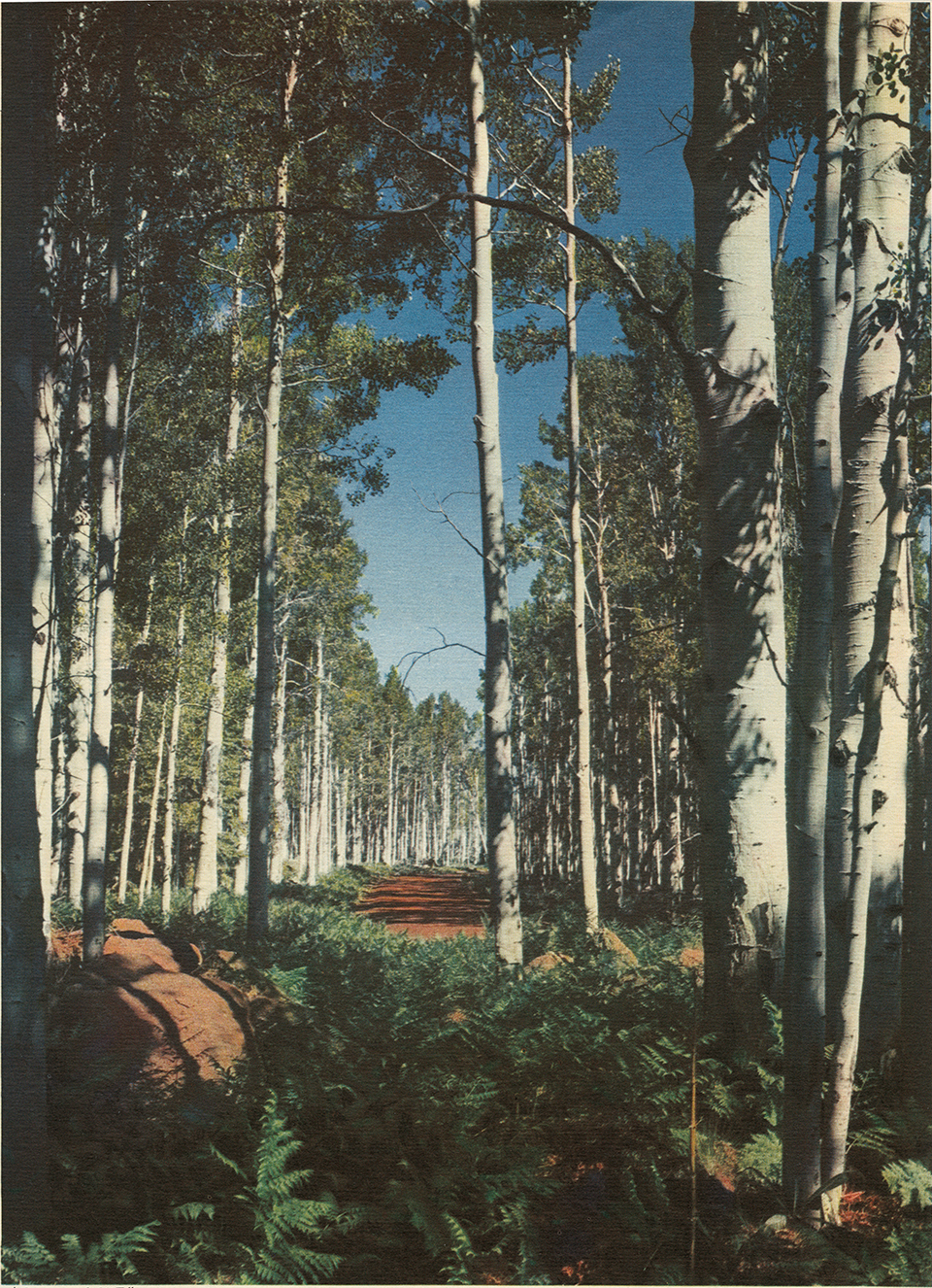

Sheep graze amid tall ponderosa pines near a watering hole in the Sitgreaves National Forest in the 1940s. | Chuck Abbott

Snows at higher elevations lure those who love winter sports, and feel happiest when tired, after a day’s great exertions, and

stretched out before an open fireplace filled with roaring pine logs. Spring weaves a lace mantilla of pale green for the white-

stemmed aspens of the Kaibab, a halo of yellow gold for the palo verde. In the northern forests autumn paints shimmering

aspen leaves with a lavish brush dipped into a paint pot of gold. As the days turn brisk, hunters add their red caps and jackets

to the scene, seeking the wide variety of wild game that made Zane Grey, noted outdoorsman, build two hunting lodges in our forests.

Summer sends those of us on the desert inside our cooled houses. Or to the forests, where sunshine is filtered through pine or fir or spruce leaves — or even the lowly liveoak and manzanita. Desert dwellers take to the woods when summer comes, for lazy outside living near a tent or travel trailer, or with just a sleeping bag to roll out beneath the stars. Our lakes are threatened now with drought. But you can still swim and skim a canoe at Lakeside, water ski at Canyon and Apache and Roosevelt, and you can fish lakes and several hundred miles of natural and man-controlled rivers and streams.

In all of the forests, wherever practical, land has been set aside for recreational uses including picnic areas, camping sites, and even cabin sites leased to individuals at modest annual fees of from $25 to $50 a year. There’s always a waiting list for these home sites, of course, and they develop slowly. It takes money to develop roads and a water supply “just for fun.”

The national forests, unlike the national parks and monuments under the Department of Interior, were not set aside as playgrounds, nor to preserve natural or historic beauty. Managed under the Department of Agriculture, the forests have two major purposes: protection of the nation’s water supply and production of timber. Farmers and ranchers graze sheep and cattle on forest lands, under lease arrangements and careful supervision.

Recreational use of the forests came about almost as an afterthought.

Not too many years ago, vacationers, hunters and fishermen were considered a “damned nuisance” in the forests. We started fires, got lost, polluted streams, stuck our noses into logging and grazing commercial enterprises where we had no practical reason for being. The general public was tolerated, but not welcomed. And we were supposed to take things as we found them, including finding a place to camp or getting through the forests. The fewer who came, and the sooner they left, the better those who ran the forests liked it.

You might almost say the Depression introduced Americans to their forests — and foresters to the public. Recreation was named one of forest land’s many uses in 1932. And the next year fish and game sanctuaries and refuges were authorized within the forests — and the Civilian Conservation Corps was organized.

In forestry alone, around 730,000 man-years were devoted by these young men in their camps, half of which were in forests. They built firebreaks, fought fire, improved timber stands, planted trees, built roads, trails, bridges, telephone lines, look-

out towers. They set up picnic tables, constructed fireplaces, dug garbage and toilet pits, installed water lines. Without the CCC, our recreational facilities in the forests would have been much slower in developing — and the forests have not yet caught up with the public’s demand. Perhaps they never will.

In Depression years, the campgrounds of the national forests were one of the few places a family could “set up camp” and live rent-free, with firewood and water available. As the Depression years dimmed into memories, the tensions of war, of a fast-paced economy, of inflation and rapidly increasing cities, sent more and more of us into the woods. In 1953, more than 35,000,000 visitors were registered in the national forests, breaking all records — topping the highest before World War II by 83 percent!

“People don’t visit the national forests just to be outdoors,” writes Bernard Frank in his wonderful book Our National Forests. “They can find fresh air, birds, and trees in the well-tamed city parks, out in the country, even on a roof top, or in the back yard. Nor do they come merely to roast hot dogs, splash in a stream, or take a sun bath. Many are impelled by a deep-seated urge to return to the ‘primitive’ and sometimes to act the role of ... pioneers in the days when virtually all America was in a natural state.

“If they return often enough, the stimulating, health-giving properties of the forest will get under their skins.” There’s something for everyone in the forests. For those who want all the comforts of home including a hot bath at night, there are excellent lodges and inns and hotels built on commercial leases in the forests and nearby. For those lucky enough to acquire them, there’s a chance for a summer home on land leased for the purpose. For all of us, when we don’t try to find one on a summer holiday or weekend, there are good campgrounds from near Douglas to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. There are many other places, reached both by main paved road as well as graded forest roads, where we can picnic.

Streams for fishermen, game for hunters, a chance to feel and hear and see and touch nature, are everywhere. But we have even more than that. We have, within our national forests in Arizona, some of the nation’s wonderful wilderness and wild areas. Robert Marshall, who is called the father of the forests’ wild areas, defined them as “regions which contain no permanent inhabitants, possess no means of mechanical conveyance, and are sufficiently spacious that a person may spend at least a week or two of travel in them without crossing his own tracks.”

In these areas often it is impossible even to ride horseback. Only hikers and mountain climbers tackle them. Commercial timber cutting is prohibited, and a man is alone with nature as it was before man discovered it — almost. Many people cannot bear a wilderness experience; once the individual learns to develop the appreciation, aptitudes, and woodsman’s skills necessary in the wilderness, he becomes refreshed, renewed, restored.

But whether your vacation means “re-creation” or just having fun, some place in Arizona’s national forests can provide it. There’s a wealth of leisure — or activity — to suit every man’s interest: camping out or skiing, picnicking, fishing, hunting, swimming, boating, mountain climbing, horseback riding, hiking, looking for unusual rocks or precious minerals, studying ancient Indian ruins, discovering fossils, examining an infinite variety of plant, animal and bird life, exploring caves and meteor craters, collecting pine cones, or just sitting — and enjoying — the solitude of the great outdoors. Hunting with a camera yields scenic rewards. Just vacationing — for an afternoon, a day, a week, a month or a summer — yields memories you’ll treasure always.

ARIZONA’S NATIONAL FORESTS

From rugged desert to alpine mountaintops, the state’s seven forests offer 12 million acres of recreational opportunities.

Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests

The Mogollon Rim and the White Mountains are the crown jewels of the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests, which have been managed as one U.S. Forest Service unit since a 1974 merger. Together, they span more than 2 million acres in Central

and Eastern Arizona. In Rim Country, visitors flock to several lakes, including Woods Canyon and Willow Springs; farther east, it’s easy to find solitude in the White Mountains’ alpine meadows and ponderosa pines. Within the forests’ boundaries are roughly 1,000 miles of trails that weave through a variety of terrain and habitat, allowing hikers to spend their days strolling through dense forests or challenging themselves with high summits. About 50 developed or dispersed campgrounds are found on the forests, and about a third of them offer fishing opportunities; more opportunities to cast a line can be found along numerous rivers and streams. “The forests in this area are unique,” forest Supervisor Steve Best says, “in regard to their resources, landscapes and employees, as well as the communities we serve.”

ACRES: 2.6 million (Arizona and New Mexico)

INFORMATION: 928-333-6280, www.fs.usda.gov/asnf

Coconino National Forest

From arid Southwestern desert to alpine tundra, with red rocks and ponderosa pines in between ... that’s the Coconino National Forest, one of America’s most diverse forest units. It covers about 1.9 million acres of mountains, canyons, lakes and creeks. It’s home to 12,633-foot Humphreys Peak, the highest point in Arizona, along with scenic drives in Oak Creek Canyon, the San Francisco Peaks and the Lake Mary area southeast of Flagstaff. In spring, summer and fall, fishing is available at a handful of the roughly 20 campgrounds on the forest, and mountain biking is another popular warm-weather activity. In winter, skiers and snowboarders have been hitting the slopes at Arizona Snowbowl since 1938. “The forest is also rich in Native American heritage and is held sacred by numerous tribes,” forest Supervisor Laura Jo West says.

ACRES: 1.9 million

INFORMATION: 928-527-3600, www.fs.usda.gov/coconino

Coronado National Forest

The Coronado National Forest, made up of several non-contiguous districts in Southeastern Arizona and Southwestern New Mexico, is known for its “sky islands” — isolated mountain ranges rising above the surrounding desert. Plants and animals atop those ranges can’t survive in the arid desert below, creating isolated ecosystems that sometimes support flora and fauna found nowhere else in the world. It also creates tantalizing opportunities for hikers and day trippers, who can start a trek in the desert heat and end it amid ponderosa pines and mountain breezes. Pitch a tent at any of the 20 campgrounds on the forest’s 1.8 million acres, or enjoy numerous opportunities for horseback riding and mountain biking. Migratory birds attract visitors from around the globe, says Kerwin Dewberry, the forest’s supervisor, adding that visitors craving solitude can explore the backcountry via the Coronado’s eight wilderness areas.

ACRES: 1.8 million (Arizona and New Mexico)

INFORMATION: 520-388-8300, www.fs.usda.gov/coronado

Kaibab National Forest

The Kaibab National Forest’s 1.6 million acres of canyons, prairies, peaks and plateaus include land directly north and south of Grand Canyon National Park; some of the forest’s 300 miles of hiking trails even cling to the Canyon’s rim. And given the forest’s range of elevations — from 3,000-foot grasslands to the 10,418-foot summit of Kendrick Peak — there’s plenty to see and do. There are seven developed or dispersed campgrounds, six designated fishing areas and 17 mountainbiking trails, along with the North Rim Parkway (State Route 67), which leads from Jacob Lake to the Canyon’s North Rim and is among Arizona’s most scenic roads. “There is not a day that goes by that I’m not amazed by the beauty, the peace, the connection and the adventure that can be experienced in this incredibly special place,” forest Supervisor Heather Provencio says. “For me, one of the most valuable things for people visiting the Kaibab National Forest is the opportunity to find solitude, quiet and clarity in the midst of the busy lives that we all lead.”

ACRES: 1.6 million

INFORMATION: 928-635-8200, www.fs.usda.gov/kaibab

Prescott National Forest

The Prescott National Forest borders three other forests — the Kaibab, Coconino and Tonto — but has wonders all its own within its 1.2 million acres of Central Arizona. The Juniper, Santa Maria, Sierra Prieta and Bradshaw mountains are there, as are the Black Hills, Mingus Mountain, Black Mesa and the headwaters of the Verde River. An easy loop drive that starts and ends in Prescott takes day trippers past three scenic lakes: Lynx, Hassayampa and Goldwater. There’s fishing at seven of the forest’s lakes and at eight sites along the Verde River, and thanks to the area’s relatively mild climate, most of them can be accessed year-round. There are nine campgrounds, too, but forest Supervisor Tammy Randall-Parker says the forest is best known for its top-notch trail system, which features 450 miles of hiking and mountainbiking routes. It’s the result, she says, of “years of collaboration between local communities, recreationists and the forest.”

ACRES: 1.2 million

INFORMATION: 928-443-8000, www.fs.usda.gov/prescott

Tonto National Forest

At nearly 3 million acres, the Tonto National Forest is the country’s fifth-largest forest. And its rugged, fascinating environment, which ranges from saguaro cactuses to pine-forested mountains, makes it easy to see why nearly 6 million people pay the Tonto a visit every year. Some of its best-known attractions are the Salt River, Saguaro Lake, the Superstition Mountains and Fossil Creek, but there also are plenty of opportunities to hike, rock-climb or explore ancient ruins. And for those who don’t think a day trip is enough time to explore 3 million acres, the forest has more than 30 developed campgrounds and more than 20 dispersed sites. Whatever your pleasure, forest Supervisor Neil Bosworth says, rest assured that “the Tonto National Forest has something for almost everyone.”

ACRES: 2.9 million

INFORMATION: 602-225-5200, www.fs.usda.gov/tonto

— Brianna Cossavella