Editor’s Note: In 1994, we published a book titled Arizona Ghost Towns and Mining Camps. It was written by Philip Varney, and it went on to become one of the best-selling books in our history — it’s currently in its 19th printing. This month, we’re excerpting a portion of that book, which defined a ghost town as a place having two characteristics: 1) The population has decreased markedly, and 2) the initial reason for its settlement (mine, railroad, etc.) no longer keeps people in the community. Tony Hillerman once said that “ghost towns offer a sort of touching-place with the past.” We agree with the great writer, and hope this collection has the same effect.

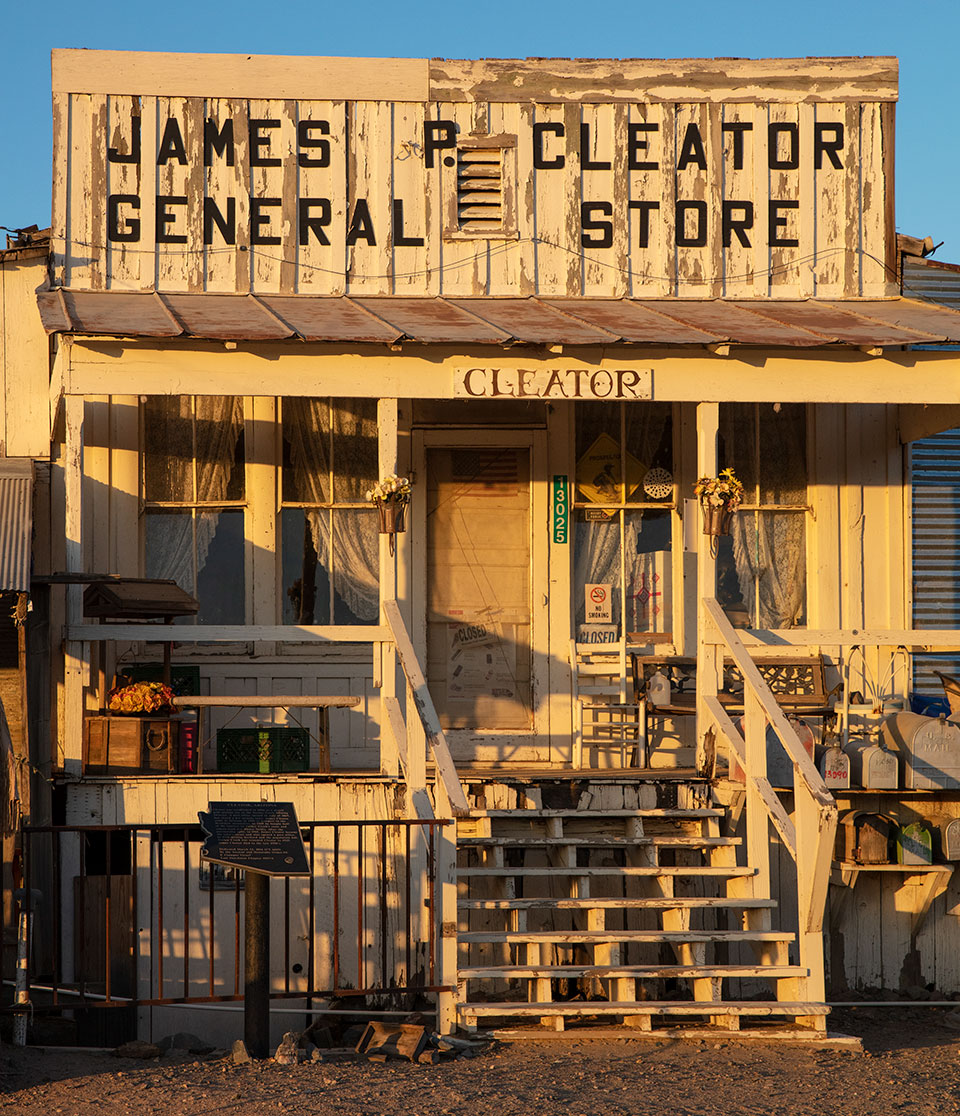

Cleator

Established 1900s

Cleator is where the old route of Murphy’s Impossible Railroad, having gone through Cedar Canyon, becomes today’s dirt road to Crown King.

The road heading south from Cordes soon drops off the plateau, and one can clearly see a small cluster of buildings along Turkey Creek, as well as the dramatic eastern face of the Bradshaw Mountains. It is hard to imagine planning, much less completing, a railroad on that formidable terrain.

The Turkey Creek Mining District was a placer gold site established in 1864 as prospectors fanned out from Walker to find the next bonanza. After a stage station was constructed 2 miles west of the creek in 1869, a post office was granted at Turkey Creek. But it lasted only five months.

The placer workings gave out quickly, but mines in the foothills took their place. By 1902, when Murphy’s Impossible Railroad reached Turkey Station (also called Turkey Creek Station and Turkey Siding), several mines were ready customers for cheap ore transportation.

Leverett “Lev” Pierce Nellis had arrived a year before. In anticipation of the railroad, he had built a store and saloon and reopened the post office. Within a couple of years, he owned most of the growing town.

James P. Cleator came to Turkey Creek soon afterward. Born on the Isle of Man in 1870, Cleator went to sea as a cabin boy at age 12. At 16, he signed on as an able seaman for a voyage to Spain. In 1889, he came to America and quit the sea. He would proudly recall that in San Francisco, he shook the hand of President Benjamin Harrison. After making $10,000 on a California mining claim, he came to Arizona via Mexico in 1900.

Cleator approached Nellis in 1905 about buying into Nellis’ business. Nellis agreed. The partnership worked so well that they expanded into ranching. In 1915 they amicably split the partnership, Nellis taking the cattle and $2,500 and Cleator getting the town. Ten years later, Postmaster James P. Cleator had the post office renamed after himself.

Cleator was a lively place where ranchers, miners and railroad workers converged. Mynne Cordes Jarman fondly remembered the Cordes girls riding to the store in Cleator for dances with local ranch hands and miners.

Cleator eventually declined in the late 1920s as mines closed. Jimmie Cleator, who had married in 1919 after almost 50 years of bachelorhood, then had a wife, two children, a shut-down mine and a ghost town. He put Cleator up for sale in 1949 but had no takers. The post office closed in 1954. Jimmie Cleator died five years later, leaving the town to his son, Tom.

A Works Progress Administration-built stone schoolhouse and about a dozen cabins still stand at Cleator. Some of the structures are now inhabited, so visitors must enjoy them from the road. The original Cleator store is closed, but the adjacent saloon, site of those gala dances, is open daily. Until his death, in 1996 at age 71, Tom Cleator hosted visitors there, telling stories of the Cleator clan, who have been such an integral part of the surrounding country. Resting in the quiet, high desert on the east slope of the Bradshaw Mountains, a little more than an hour’s drive from Phoenix, Cleator is a relaxing place to stop and seems like a thousand miles and a hundred years away from modern city life.

Traversing Murphy’s Impossible Railroad is not impossible at all. The dirt road heading southwest from Cleator is the roadbed of the old Bradshaw Mountain Railroad. Evidence of this are backfilled dips, gentle curves and deep cuts made in the rock — traits that are roadbed requirements for trains, not automobiles. About 2.5 miles out of Cleator, the road passes the site of Middleton, where a 0.75-mile-long tramway once delivered ore to the railway from the De Soto Mine. Remnants of that tramway extend west up the mountain to the mine.

After climbing gently, the roadbed becomes a series of very steep switchbacks. Most motorists think a “switchback” is simply a hairpin turn. But to a railroader, it’s something very different. At a switchback, the train goes into a spur beyond the turn, a switch is thrown, and the train backs up to the next such switchback, where the process repeats itself and the train goes forward once again. The railroad to Crown King had five pairs of these switchbacks. The road today follows two of the pairs. Motorists should be sure to look at the cutaways the railroad made to allow the switches to be thrown. If the turn goes to the right, for example, look left to see where the train was positioned to climb the next part of the grade.

At places where trestles were used, the old roadbed clearly heads off into space (now blocked by earth and/or signs). Today’s dirt road takes much tighter turns until rejoining the railroad bed. An interesting sidelight: When the tracks were taken up in 1927, Model T-era vehicles drove the trestles on boards strung along the towering structures at wheel width. There was little room for error in judgment. There was also very little drinking at weekly dances, held in the schoolhouse at Crown King, as participants considered the treacherous midnight drive home.

Nearing its destination, the dirt road detours around a now-collapsed tunnel, crosses a bridge and enters a forested paradise. Welcome to Crown King.

Directions: From Black Canyon City, go north on Interstate 17 for 14 miles to Bloody Basin Road (Exit 259). Turn left (west) onto Bloody Basin Road and continue 3.4 miles to Antelope Creek Road (County Road 179). Turn left onto Antelope Creek Road and continue 2.8 miles to a “Y” intersection. Veer right, toward Crown King, and continue 1 mile to County Road 59. Turn right onto CR 59 and continue 3.6 miles to Cleator. Some of the route is unpaved, but it’s suitable for most vehicles in good weather.

CONGRESS

Established 1890s

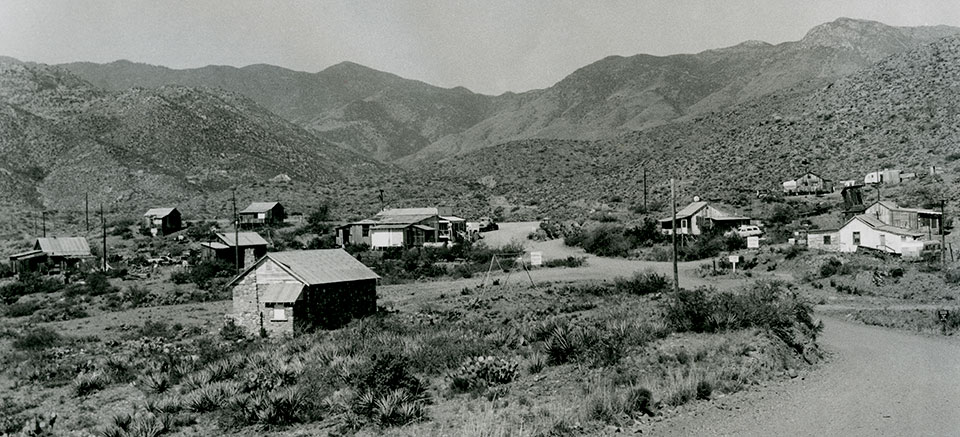

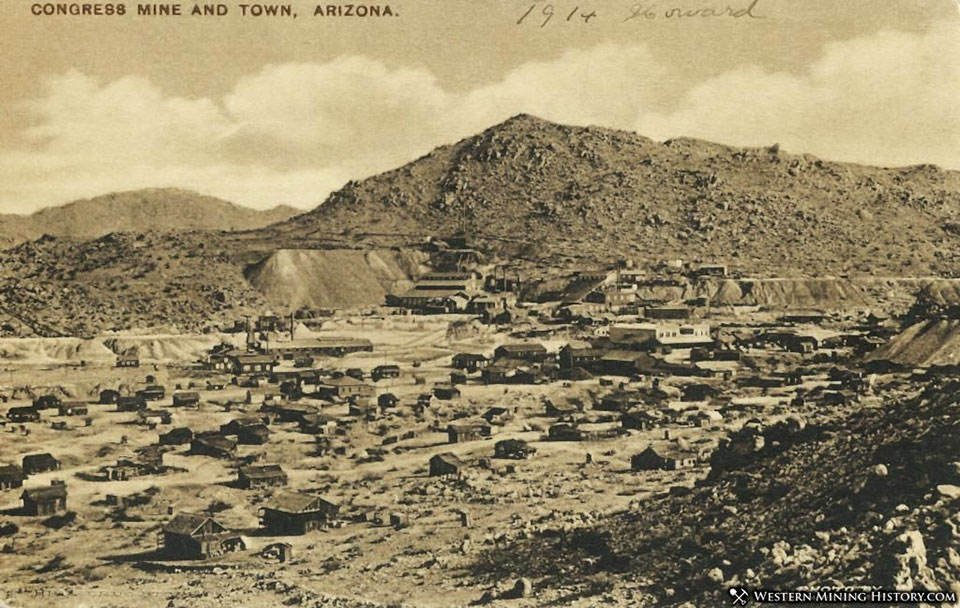

Congress is an excellent example of just how much can disappear into the Arizona desert. The community was actually two separate places. “Mill Town,” closer to the mine, featured the mill, company offices, a hospital and residences. “Lower Town,” located farther south, boasted the commercial district, including restaurants, the usual stores and saloons, two churches, and a school. Virtually nothing but debris remains at either site, except for lasting testaments to man’s presence: two cemeteries.

Congress sprang into existence after Dennis May’s 1884 discovery of gold ore. The mine was sold in 1887 and then again in 1894, when the boom period began. The cost of transporting ore to market, the major shortcoming of many Arizona mines, was easily solved at Congress: By 1893, the Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railway passed within 3 miles of the mine.

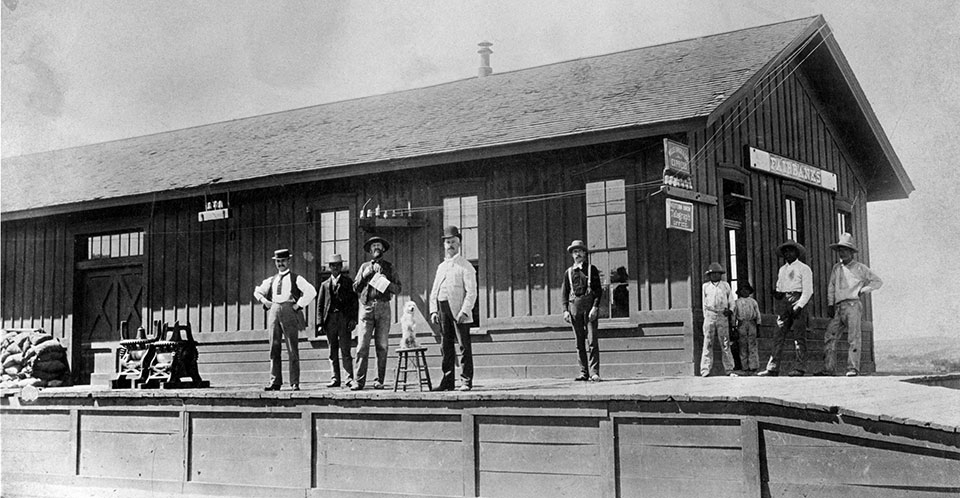

The station, known as Congress Junction, gave life to a small community that featured its own post office. In 1899, the Congress Consolidated Railroad was completed between the mine and Congress Junction.

The mining town prospered into the mid-1930s. The post office at Congress closed in August of 1938, and its name was transferred to the post office at Congress Junction on November 1 of that year. For all intents and purposes, the railroad community had become the only Congress and is so to this day.

The former Congress Junction has the only buildings for the ghost town enthusiast. The old Congress Hotel and a few other structures sit along State Route 89 just south of State Route 71. Until recently, the original school, across the railroad tracks to the west, housed the Congress Community Center, but that building was damaged in a 2014 monsoon storm and ultimately demolished. A historical marker still stands at the now-vacant lot along Santa Fe Road.

The two cemeteries are reached, appropriately, via Ghost Town Road, which heads north from SR 71 west of the railroad tracks. Follow the road for almost 2 miles. Signs direct you first to the Congress Cemetery and then to the Pioneer Cemetery.

The two silver flagpoles of the Congress Cemetery are easy to spot, although flags are not always flying. From the main route to the cemeteries, this site is reached via a dirt road on the left. Among several interesting grave markers is that of Oscar McElroy, who was born in Center Point, Texas, in 1880 and buried at Congress in 1903 (see back cover). The inscription reads: “Sleep on dear boy, now take thy rest. God called thee home, he thought it best.”

The Pioneer Cemetery is 0.6 miles farther down the road, which eventually loops back to Ghost Town Road. (Segments of this route require a high-clearance vehicle.) To prevent further vandalism, graves are protected by a locked gate. At least eight infant graves grace the site. Eloicita Mouelthrop died in 1898 at the age of 1 month and 10 days. Joseph Villetti was just beginning his third year of life when he died in 1897. The marker says his death was “regretted by his beloved parents.” His epitaph: “Gone to be an angel.”

Directions: From Wickenburg, go northwest on U.S. Route 93 for 6 miles to State Route 89. Turn right (north) onto SR 89 and continue 10 miles to Congress. The entire route to the town is paved, but a high-clearance vehicle is recommended for the road to the cemeteries.

COURTLAND

Established 1900s

Today, there are sparse remnants of Courtland, whose last resident died in the 1970s. The surviving buildings include a concrete jail, a collapsing store, stone walls, foundations and considerable mining evidence. If you keep driving along Ghost Town Trail, you can’t miss most of the structures — especially the jail, which is near the road and is on land owned by a mining company. Other areas of the town have recently been purchased by the Arizona Land Project, which plans to preserve some of the structures and make them available for public tours.

You wouldn’t guess it today, but long ago, Courtland thrived. In 1909, several hundred people swarmed to the region as the Calumet and Arizona, Copper Queen, Leadville, and Great Western mining companies all began operations. The Great Western was owned by W.J. Young, who named the town for his brother Courtland. Eventually home to about 2,000 people, the settlement had a post office, two newspapers, a movie theater, a butcher shop, an ice cream parlor, a pool hall, a Wells Fargo office, the Southern Arizona Auto Co. and the Mexico and Colorado Railroad, a branch line extending north from Douglas.

The town survived into the Depression but lost its post office in 1942. By that time, many of the buildings had already been moved or razed.

Many open shafts, some unfenced, are near the town site. Those walking around Courtland should exercise extreme caution.

Directions: From Tombstone, go southeast on State Route 80 for 0.7 miles to Camino San Rafael. Turn left (north) onto Camino San Rafael and continue 1.1 miles to Gleeson Road. Turn right onto Gleeson Road and continue 15.5 miles to Ghost Town Trail. Turn left onto Ghost Town Trail and continue 3.5 miles to a “T” intersection. Turn left to stay on Ghost Town Trail, then continue 0.4 miles to Courtland. Some of the route is unpaved, but it’s suitable for most vehicles in good weather.

dos cabezas

Established 1900s

Dos Cabezas, where Ewell Spring is located, was the next dependable source of water west of Apache Spring. A stage depot was built here, and in the late 1870s, gold and silver were found in the Dos Cabezas Mountains (Spanish for “Two Heads,” for the prominent twin peaks) above the spring. The resulting town took its name from the peaks.

On the highway through Dos Cabezas, one can see an adobe commercial building still under roof, several plastered adobe walls (some of them mostly hidden by mesquite limbs), remnants of residences and some occupied buildings, including a two-room bed and breakfast. A picturesque cemetery is on a hillside west of town.

Directions: From Willcox, go east on State Route 186 for 14.7 miles to Dos Cabezas. The entire route is paved.

fairbank

Established 1880s

Fairbank was a satellite community to Tombstone. It came into existence in 1882 with construction of the New Mexico and Arizona Railroad. This short line was a link between the Southern Pacific tracks in Benson and the border town of Nogales. Fairbank was created where the track turned west. Its proximity also turned Fairbank into Tombstone’s supply depot. Named for Nathaniel Kellogg Fairbank, a Chicago grain broker and a founding member of the Grand Central Mining Co. in Tombstone, the town probably never had more than 300 people. It did, however, have a maze of tracks: Three separate railroads eventually located depots there. Besides the line to Nogales, one went to Bisbee, and a branch eventually extended into Tombstone.

During futile attempts to reopen Tombstone’s mines, Fairbank was the site of a train robbery involving one of Arizona’s most respected lawmen, Jeff Milton. In February of 1900, Milton rode in an express car guarding a Wells Fargo box, and a gang rushed the train at its stop in Fairbank. Milton fatally wounded one of the five robbers. Then a shot splintered his left arm, but he managed to throw the strongbox key out into the brush. A crowd gathered, and the robbery was aborted.

One bandit escaped to Mexico, but the other three were captured. Milton was taken by rail to a surgeon in San Francisco. Told that his arm had to be amputated, he said, “The man who cuts off my arm will be a dead man.” Not surprisingly, his arm was spared and he regained partial use of it.

Now, with several good 1880s buildings remaining, Fairbank is part of the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area under the Bureau of Land Management. The Fairbank Commercial Co., a large adobe structure, was in danger of collapse, but the BLM stabilized it. A few houses and a gypsum-block school, circa 1920, stand north of the mercantile. The public can take self-guided tours or walk a 4-mile loop trail that passes the town’s mill and cemetery. The school now houses a bookstore, museum and gift shop open from 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Fridays through Sundays.

Directions: From Tombstone, go northwest on State Route 80 for 3 miles to State Route 82. Turn left (west) onto SR 82 and continue 6 miles to Fairbank. The entire route is paved.

Information: San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, 520-258-7200 or www.blm.gov/arizona

gleeson

Established 1900s

Gleeson and the hills at the southern end of the Dragoon Mountains had long been mined by the Indians for decorative turquoise. When white men came in the 1870s, they found copper, lead and silver as well, but they still named their camp Turquoise. The town received a post office in 1890, but the mines closed down and the town was abandoned after Jimmie Pearce found gold at the Commonwealth claim in 1894. Then, in 1900, a Pearce miner and Irishman named John Gleeson prospected the Turquoise area and filed claims for the Copper Belle mine. Mines with names such as Silver Belle, Brother Jonathan, Pejon and Defiance joined the Copper Belle. The town site was moved from the hills down onto the flats to be closer to a more reliable water supply, and Turquoise, which had lost its post office in 1894, reopened as Gleeson.

John Gleeson sold out by 1914, but the boom continued, and copper production rose due to World War I. After the war, prices fell, production declined, and the mines shut down. The post office closed its doors for the last time in 1939.

Gleeson is well worth exploring. From the intersection of Gleeson Road and High Lonesome Road, head east and look on the north side of Gleeson Road for the long adobe ruins of the hospital, with mining evidence in the hills behind. On the same side of Gleeson Road, west of the hospital, is a partly collapsed saloon and store that had an off-again, on-again existence for decades. Go north on High Lonesome Road to see an old building’s foundation and some miners’ quarters. Farther north, the road passes the adobe ruins of the Musso house (posted against trespassing). A Prohibition-era rumor suggested the Mussos sold bootleg liquor and stored it beneath a shallow fishpond in the backyard.

South of Gleeson Road on High Lonesome Road is the restored jail (virtually identical to the one at Courtland), which serves as a museum. It’s open the first Saturday of every month, or by appointment. Farther south, you’ll find the foundations of the school. The final stop in Gleeson is the Gleeson Cemetery, which is west of town, on the north side of Gleeson Road.

Directions: From Tombstone, go southeast on State Route 80 for 0.7 miles to Camino San Rafael (look for the sign for Gleeson). Turn left (north) onto Camino San Rafael and continue 1.1 miles to Gleeson Road. Turn right onto Gleeson Road and continue 14 miles to Gleeson. The entire route is paved.

Information: Gleeson Jail, 520-609-3549 or www.gleesonarizona.com

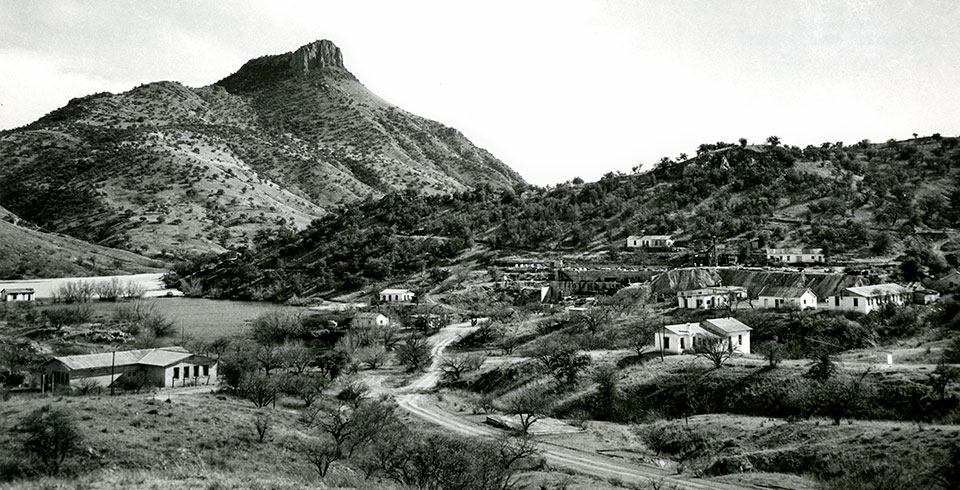

harshaw

Established 1870s

Rancher David Tecumseh Harshaw should have thanked Tom Jeffords for making him a rich man. When Harshaw was grazing cattle on Apache land in 1877, Jeffords, an Indian agent, ordered him to remove them. Harshaw relocated his herd to this area and discovered a tremendously rich silver vein, which he named the Hermosa. Within two years, Harshaw, who named the mining town that rose near the mine after himself, had sold his holdings to a New York concern and moved on.

The Hermosa Mine, located due south of Harshaw up a jeep trail, became the major producer in the area (peaking at a reported $365,654 during a four-month period in 1880). The population of Harshaw reached an estimated 2,000. The town’s life span, however, was very short. A violent thunderstorm, a fire and a drop in ore quality led to its demise. An 1882 article in The Tombstone Epitaph told of a place where 80 percent of the more than 200 buildings were unoccupied, with “windows smashed and doors standing open.” This is the same Harshaw that only two years earlier had its own newspaper, the Arizona Bullion, and a bustling, mile-long main street with a reported seven saloons.

Harshaw had two minor rebirths. One began in 1887, when Tucsonan James Finley purchased the Hermosa claim for $600. This time, the mining lasted longer but on a much smaller scale, and only about 100 residents lived in the town. In 1903, Finley died, and the market price of silver subsequently dropped significantly. By 1909, the town was a ghost once again.

The community of Harshaw last saw limited life from 1937 until 1956 as the Arizona Smelting and Refining Co. worked the nearby Flux and Trench mines.

An adobe residence, formerly with a tin roof that’s now been removed, marks the intersection of Forest Road 49 and the private side road that heads east into what is left of the Harshaw community. Down that private road about 400 yards stands the site’s primary remnant, Finley’s once-elegant brick residence.

The wooden porch, with its graceful, curving tin roof, and the skillful brickwork make the Finley home one of Arizona’s most architecturally pleasing historic buildings. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. The landowners allow visitors to see the house, provided that they stay on the road, respect all “Private Property” signs and do not venture closer to the house or any farther down the road.

A small, interesting cemetery is situated on a hillside west of FR 49, the road from Patagonia, across cottonwood-lined Harshaw Creek. Some of the headstones and wrought iron markers date from the 1880s.

One particularly poignant marker reads: “Freddie Lee Sorrells. Born February 14, 1880. Died June 5, 1885. A little time on Earth he spent, till God for him an angel sent.”

Directions: From State Route 82 in Patagonia, go south on Taylor Avenue for 0.1 miles to Harshaw Road. Turn left onto Harshaw Road and continue 5.9 miles to Forest Road 49. Turn right onto FR 49 and continue 2 miles to Harshaw. Some of the route is unpaved, but it’s suitable for most vehicles in good weather.

Information: Sierra Vista Ranger District, 520-378-0311 or www.fs.usda.gov/coronado

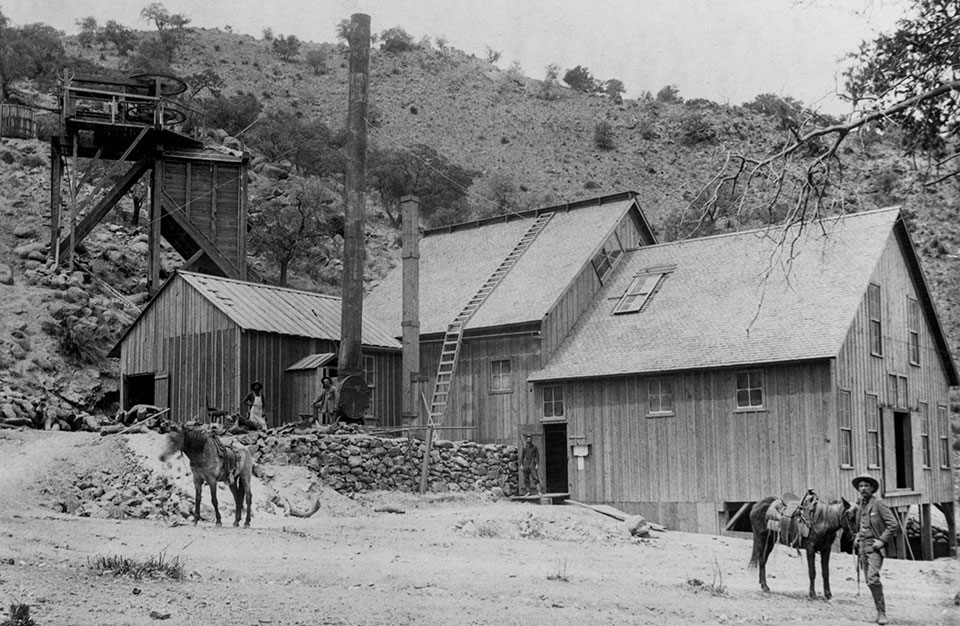

humboldt

Established 1890s

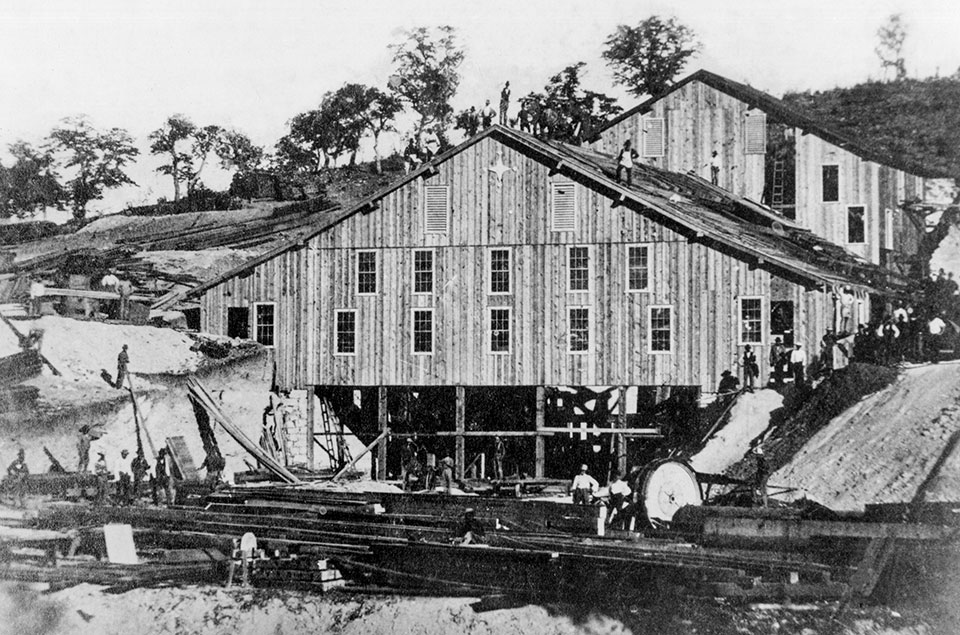

The Humboldt area was settled in the 1860s. This community in the Agua Fria Valley was originally called Val Verde, for a smelter of that name that processed the copper and lead of the Blue Bell and De Soto mines. At one point the Blue Bell, owned and operated by the Consolidated Arizona Smelting Co., shipped 11,000 tons of ore monthly. The commercial section of town was built on a ridge, with Main Street running down the center. Company houses and other buildings occupied the gulches on either side, while high-class houses were located on Nob Hill, near the smelter.

A post office opened in 1899 as Val Verde but was renamed Humboldt in 1905 to honor Baron Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), who had predicted more than a century earlier that “the riches of the world would be found” in the vicinity of the Bradshaw Mountains. As other mines were discovered in the area, more ore was sent to Humboldt. The expansion of smelting operations naturally meant prosperity for the town. The community eventually had a school, a telephone exchange, a bank, an icehouse, a hospital, the Tisdale Hotel, Wingfield’s Mercantile, the Humboldt Commercial Co., saloons and pool halls.

In the midst of the prosperity, however, two fires struck the community. The first, in 1909, burned down the Tisdale Hotel and the Humboldt Commercial Co. The second, a year later, destroyed 15 buildings in one of the gulches.

After World War I, the mines shut down and smelting ceased. The town was deserted by 1924. A 1926 article in the Miami Silver Belt warned, “Another lesson to be learned from the experience of Humboldt is that any community should strive earnestly and consistently to work itself out of a situation wherein its commercial and industrial existence is entirely dependent upon a single industry.” That is much easier said than done. However, Humboldt was resurrected in 1934, when Fred Gibbs acquired the Iron King Mine, which produced more than $100 million in lead and zinc until its closure in 1968.

Today only one stack, some slag piles and the brick walls of the smelters remain. In 1955, a stack built in 1899 was deemed a hazard, so school was recessed to let children watch the old stack topple. These days, access to the smelter is closed, but visitors can view it from the closed gate on Main Street, where signs indicate the site is being studied for cleanup under the Environmental Protection Agency’s Superfund program. Several false-front buildings from the 1920s and ’30s remain on Main Street, as does the Bank of Humboldt. The bank failed in the ’30s, and the building now is labeled as a private residence. Among the modern-day attractions on Main Street is Jackie Boyz Little Italy, a well-regarded Italian restaurant.

Directions: From Prescott, go east, then south on State Route 69 for 17 miles to Main Street. Turn left onto Main Street and continue a quarter-mile to Humboldt. The entire route is paved.

Information: Town of Dewey-Humboldt, 928-632-7362 or www.dhaz.gov

pearce

Established 1890s

Pearce was named for Jimmie Pearce, a man who tired of being a Tombstone miner after the boom years waned and pickings were slim. He and his wife, who ran a boardinghouse, were saving their money to buy a piece of the great outdoors. They managed, finally, to purchase some ranchland northeast of Tombstone. One day in 1894, while out surveying his spread, Jimmie found free gold on the side of a hill. He was back in the mining business — but as an owner, not a laborer.

A town grew at the base of Jimmie Pearce’s Commonwealth Mine. A post office opened in 1896, and the population swelled to about 1,500 as commercial businesses, which eventually included a motion-picture theater, lined both sides of a long main street.

Jimmie Pearce sold the Commonwealth for $250,000. His wife, remembering harder times, inserted a clause into the contract granting her the sole right to operate a boardinghouse at the mine, which operated into the 1930s.

Today, there are some newer structures in the area, but several buildings remain from Pearce’s heyday, including a school, a jail, a few ruins and foundations, and the remarkable Old Store, built in 1894 by the Soto brothers and Charles Renaud. The mercantile is a large adobe building with a high false front and an elaborate tin facade. It’s listed on the National Register of Historic Places, as is the nearby Our Lady of Victory Catholic Church.

The Pearce Cemetery is west of town, on the way to Middlemarch Road, a trail across the Dragoon Mountains taken by soldiers trekking between Fort Bowie and Fort Huachuca in the 1870s and ’80s.

Directions: From Tombstone, go southeast on State Route 80 for 0.7 miles to Camino San Rafael. Turn left (north) onto Camino San Rafael and continue 1.1 miles to Gleeson Road. Turn right onto Gleeson Road and continue 15.5 miles to Ghost Town Trail. Turn left onto Ghost Town Trail and continue 3.5 miles to a “T” intersection. Turn left to stay on Ghost Town Trail, then continue 10 miles to Pearce. Some of the route is unpaved, but it’s suitable for most vehicles in good weather.

ruby

Established 1910s

Ruby, for decades, was a place ghost-town enthusiasts looked upon with something approaching hunger. They knew it was one of the premier ghost towns in the country. Only Vulture (near Wickenburg) rivals it for number of standing buildings. Yet Ruby was completely off-limits to visitors, naturally whetting their appetites as they gazed longingly past the locked gate. The town later opened to visitors who paid for a permit, but as of 2024, it's again off-limits to the public; however, you can see parts of Ruby with binoculars from the road. And the journey is well worth taking.

The area at the base of Montana Peak was first mined in the 1870s. The settlement that grew from the diggings became known as Montana Camp. Primary ore deposits showed lead, silver, gold, zinc and copper.

Store owner and Postmaster Julius Andrews gave the town its name when the post office was established in April 1912, two months after statehood. He named the post office — and effectively the town — for his wife, Lillie B. Ruby Andrews.

Philip C. Clarke purchased the Andrews store in 1913 and built a larger version up on a hill, where its ruins still stand. Because Ruby was so close to the Mexican border and raids in the area were all too common, Clarke and his wife, Gypsy, kept firearms in every room of their house and store.

On one occasion, the lives of the Clarke family may have been saved by a tall tale. During a time when all ranchers and miners were concerned about cross-border raids by Mexican revolutionaries, Clarke was asked by an old man named Guzman what the new pipe apparatus was in front of his store. Clarke loved to kid the serious old man, so he told him that it was an elaborate device by which he could release a spray of poison gas with a master switch in his bedroom. He said it was strong enough to wipe out a regiment. Clarke enjoyed a good laugh as the old man made a wide detour around the cylinder. In truth, the device was nothing but a rain gauge.

When Guzman returned about a month later, Clarke asked him if he had encountered any revolutionary soldiers. “Oh, yes. … They went through everything I had. But they took only my tobacco.” Clarke then asked if the soldiers had considered coming to the Ruby store. Guzman replied, “Yes, they asked me all about it and I told them about that thing you have there — that thing that shoots poison gas.” The soldiers decided to avoid the Ruby store. From then on, Clarke said, “I was very careful to tell everyone about my ‘death-dealing machine.’ ”

Others were not as lucky. Clarke leased the store to Alex and John Fraser in 1920, warning them to keep well armed, especially when behind the counter. Less than two months later, Alex lay dead by the cash register and John, shot in the eye after being forced to open the store safe, lived only a few hours longer. One of the two bandits was later killed resisting arrest, but not before killing a deputy. The other was never apprehended.

Clarke was still feeling guilty about the situation in which he had put the Fraser brothers when Frank Pearson approached him about purchasing the store. Pearson brushed words of caution aside, arguing that lawlessness had decreased sufficiently and that another attack was highly unlikely. Pearson became the store’s next owner, and on August 26, 1921, he and his wife were killed by seven armed men. Their young daughter, Margaret, fell while trying to escape; she looked up to see her pursuer stop over her and then, unaccountably, turn and walk back inside the store. Margaret Pearson Anderson, her life spared for whatever reason, lived to become a teacher and reading specialist in Nogales and Tucson, retiring in 1980.

Two of the seven bandits were recognized as they fled Ruby. Placido Silvas and Manuel Martinez were taken into custody, tried, convicted and sentenced to hang. The sheriff’s car transporting them to Florence overturned, killing the sheriff and injuring his deputy. Martinez was later recaptured and hanged at the Florence prison. Silvas was never found.

The most prosperous period for Ruby began in 1926, when the Eagle-Picher Lead Co. took over operations. The town boasted electricity (supplied by diesel engines), a doctor, a hospital and a school with eight grades and three teachers. From 1934 to 1937, the Montana Mine was the leading producer of lead and zinc in Arizona. In 1936, it was third in silver production. But the ore played out in 1940, and by 1941, the town that once claimed 1,200 residents became a ghost.

Today, Ruby has more than two dozen buildings under roof. The Clarke store, which was habitable until the 1970s, has completely collapsed, but the sturdy jail next door remains. The school stands nearby, with two toppled teacherages (now reduced to piles of lumber) adjacent to the playground.

On the southern side of the town site are mine offices, mill foundations, mine officials’ residences and a miners’ dormitory. Several of the southern buildings are visible from the road or atop a small hill.

Directions: From Nogales, go north on Interstate 19 for 7.2 miles to Ruby Road (Exit 12). Turn left (west) onto Ruby Road and continue 10 miles to a “T” intersection. Turn left to stay on Ruby Road, then continue 14.2 miles to Ruby. A high-clearance vehicle is required.

Information: Ruby Ghost Town, 520-744-4471 or www.rubyaz.com

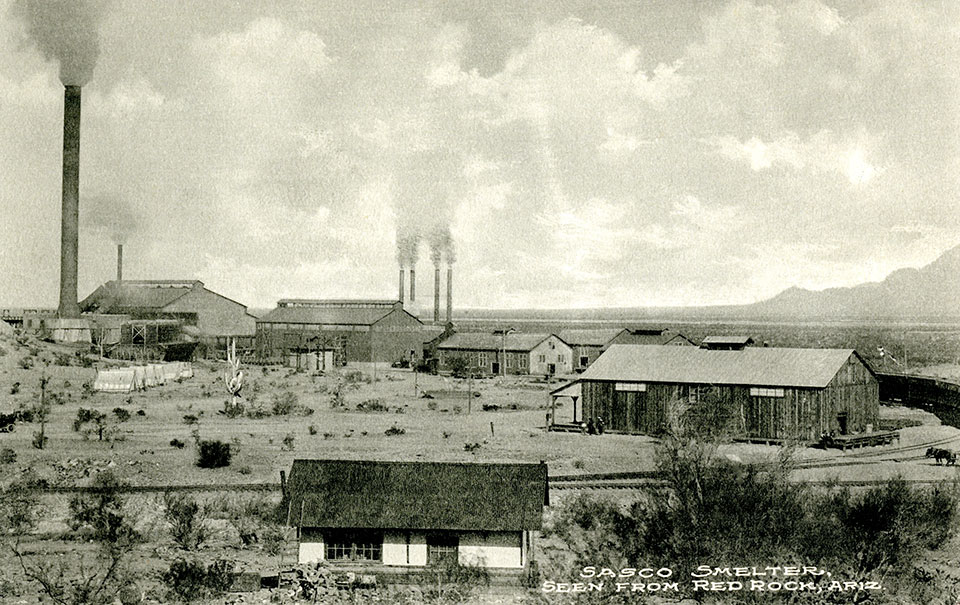

sasco

Established 1900s

Sasco — its name an acronym for the Southern Arizona Smelting Co. — once was a community of about 600, and it featured a smelter, associated company buildings, residences, saloons, stores and the Hotel Rockland. A post office served the community from 1907 to 1919. Today, remnants of Sasco are scattered over a wide area.

From Interstate 10, it’s a 7-mile journey, much of it beside irrigation ditches and cattle pens, through Red Rock to the Sasco area via Sasco Road. The Arizona Southern Railroad followed the same route from its connecting point with the Southern Pacific Railroad. From Sasco Road, head north 0.6 miles to a “Y” intersection, where you’ll find the Sasco Cemetery. Among the memorials are several concrete crosses, reminders of the devastating influenza epidemic of 1918-19 that claimed more than a half-million American victims. You can view the cemetery from the road, but the gates are locked and “No Trespassing” signs are posted.

Continuing west on Sasco Road, you’ll see the volcanic stone walls of the Hotel Rockland — vandalized, spray-painted and forlorn — on the north side of the road. West of the hotel stands a structure that says “City Hall” but actually was a jail. Farther west, a road to the north leads from Sasco Road to the ruins of the smelter.

An exploration on foot leads to the old smelter stack base, the smelter foundations, a series of concrete monoliths, an enormous slag pile and a railroad platform.

The final stop in Sasco is a bit farther west, on a minor dirt road that heads south from Sasco Road. On this road, you’ll find a concrete powder house, foundations of adobe buildings and a waterless stone fountain.

Directions: From Tucson, go northwest on Interstate 10 for 32 miles to Red Rock (Exit 226). Turn left to cross over the freeway, then continue 0.2 miles to a “T” intersection. Turn right and continue 0.2 miles to Sasco Road. Turn left onto Sasco Road and continue 7 miles to Sasco. Portions of the main road and many of the side roads require a high-clearance vehicle. Additionally, Sasco Road crosses several washes, so do not attempt the drive after recent rain or if rain is in the forecast.

Stanton

Established 1860s

Stanton, originally called Antelope Station, was a small community that developed along Antelope Creek. Most of the residents were miners, but some merchants settled there, too, providing goods and services. The stage station owner was an Englishman named William Partridge. The general store was owned by G.H. “Yaqui” Wilson. Pigs belonging to Wilson broke into Partridge’s property, beginning an enmity that was to serve a newcomer well.

Charles P. Stanton came to Antelope Station in the early 1870s, having left the post of assayer at the Vulture Mine. He conceived a plan to use the Partridge-Wilson feud to eliminate both men, which he believed would leave the two principal commercial enterprises of Antelope Station in his hands. He told Partridge, “The owner of the pigs is out to get you,” a statement that was patently false. Partridge, however, believed the threat and shot Wilson on sight. Partridge was arrested, tried, convicted and sentenced to prison in Yuma, where he claimed to be haunted by Wilson’s ghost.

However, things didn’t immediately go as Stanton had planned. Wilson had a silent partner named Timmerman. And the incarcerated Partridge had creditors, who sold his stage station to Barney Martin. Undeterred, Stanton hired a group of desperadoes led by a man named Francisco Vega to dispose of Timmerman. This done, in 1875 the town was renamed Stanton, with Charles Stanton as postmaster. Besides Stanton, the only remaining person of power was Martin. In July of 1886, the remains of Martin, his wife and their children were found in a charred wagon not far from town.

Charles Stanton brutally achieved the control he sought. But not for long. In November of the same year, a young member of the Vega gang, Cristero Lucero, shot Stanton to death because Stanton had insulted his sister. As he fled town, Lucero met another Stanton adversary, Tom Pierson. When Lucero told him what he had done, Pierson is said to have replied: “You don’t have to pull out. If you stick around, you’ll get a reward.”

Within four years, Stanton, the town, was almost as dead as Stanton, the man. The post office closed in 1890 as mines played out, then reopened in 1894 along with the mines. About 200 people lived in the community, which featured a new store, a boardinghouse, homes and a five-stamp mill. The post office closed for good in 1905.

For many years Stanton was closed to the public, which probably accounts for its restorable state. Since purchasing the site in 1978, the Lost Dutchman’s Mining Association has improved roofing, shored walls and, happily, allowed the public to visit. The group also has developed the surrounding area and added amenities such as RV hookups. Only a few original buildings stand at Stanton today, but they are excellent reminders of the Old West.

One is Charles Stanton’s old stage stop and store, in which he was murdered by Lucero. Another building, the most substantial structure on the site, was a saloon and now serves as a recreation hall.

At the north end of the interior, one can see where a shelf once was attached to the wall. It is not widely known, thanks to Western movies, that most saloons in the Old West did not have tables and chairs. Men stood around the periphery of the room, facing the center, their drinks positioned behind them on a narrow sill. This allowed imbibers to keep an eye on each other and anyone who came through the door. In a town with the likes of Charles Stanton, Vega and Lucero, the arrangement had definite advantages.

The weathered Hotel Stanton is the other outstanding building at the town site. Originally Partridge’s stage station, the hotel features a main lobby and a series of rooms stretching down a boardwalk, each with its own front and back doors — another prudent architectural consideration for a town with a treacherous past.

Directions: From Wickenburg, go northwest on U.S. Route 93 for 5.3 miles to State Route 89. Turn right (north) onto SR 89 and continue 11.8 miles to Stanton Road. Turn right onto Stanton Road and continue 6.5 miles to Stanton. Some of the route is unpaved, but it’s suitable for most vehicles in good weather.

swansea

Established 1900s

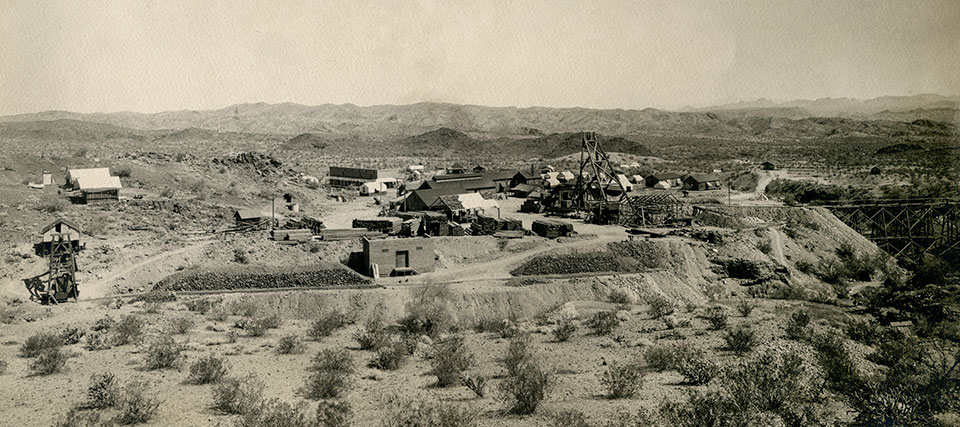

photographer. | John Burcham

The dusty ruin of Swansea, a premier ghost town, is situated about 4 miles south of the Bill Williams River, one of West-Central Arizona’s largest rivers. While Swansea saw only a few good years before it was left for the desert to reclaim, its remains are eerie and intriguing. The town site is not dotted with shops, as are Jerome, Oatman and Bisbee. Instead, Swansea is an abandoned wreck of its former self, deserted in the middle of nowhere.

Today, the site includes the brick walls of a large smelter; a double row of gray-plastered quarters for single men; the adobe walls of mining officials’ homes; a company store foundation; a train depot; and dump sites of the mine, mill and smelter.

Another 4 miles north on a tortuous four-wheel-drive trail brings you to the Bill Williams River and the remnants of the pumping plant that once supplied Swansea’s water. All this only hints at the town’s original size.

The site is managed by the federal Bureau of Land Management, which established the Swansea Town Site Special Management Area in an attempt to stop vandalism and deterioration. In partnership with Friends of Swansea Inc., the BLM has carefully restored roofs to some buildings, including the single-men’s quarters, and shored up others. The BLM also established an interpretive trail and installed vault toilets for visitors. When you arrive, sign in at the BLM register along the entrance road and pick up a brochure, which includes a map of structures you can visit in Swansea.

It is difficult to imagine that this site once boasted theaters, restaurants, saloons, barbershops and even an automobile dealership. The showplace residence was a two-story, 3,600-square-foot adobe home with a palm-tree-lined entrance.

As was often the case in early mining towns, the men who worked in the mines lived in the shadow of those civilized elements. They were primarily Mexicans and Colorado River Indians, people not welcome in the theaters and unlikely to patronize a car dealership.

The area was first prospected in 1886 by three men who were disappointed when the veins showed principally copper and only small amounts of silver. Ten years later, one of the men returned with new partners because copper was becoming more valuable. Still, little actual mining took place due to the high cost of transporting ore from such a remote place.

Then, in 1904, a rail line was proposed from Congress to Parker, along the Colorado River and into California. By the time the Arizona and California Railroad was completed in 1907, claims had been consolidated in the region as the Clara Gold and Copper Co., and a mining camp began to grow.

Unfortunately for Swansea, George Mitchell, a metallurgist and the principal promoter for the mining company, was a better promoter than he was a metallurgist. He poured money into embellishments that impressed investors rather than into improvements that enhanced the mining of ore. As a result, the cost of producing copper was 3 cents per pound higher than its selling price.

As mining expert Harvey Weed wrote in his 1913 Mines Handbook, Mitchell’s vision of Swansea was “an example of enthusiasm run wild, coupled with reckless stock selling and the foolish construction of surface works before the development of enough ore to keep them busy.”

Mitchell left Swansea in 1916 to join another operation. After his departure, or perhaps because of it, Swansea managed to make a profit for two years. Ironically, Mitchell’s smelter did not process the ore — it was sent to Clarkdale, Humboldt and Sasco.

Swansea’s short-lived prosperity ended after World War I, when copper prices plummeted. By 1937, the town was a thoroughly scavenged ghost.

Although other mining camps have more substantial ruins and are much easier to reach, Swansea’s appeal is enduring. The desert can be harsh, but it can also be stunningly beautiful and serene. While it was no doubt a difficult place to live and work, it is now a marvelous place to escape the modern world. Camping out at Swansea — with no power lines, televisions or air conditioners, and with only coyotes, hummingbirds and other wildlife as neighbors — is a rare experience indeed.

Directions: From Parker, go south on State Route 95 for 1.5 miles to Shea Road. Turn left (east) onto Shea Road and continue 13.3 miles to Swansea Mine Road. Turn right onto Swansea Mine Road and continue 17.7 miles to Swansea. A high-clearance, four-wheel-drive vehicle is required. Additionally, visitors should know that the Swansea area is extremely remote, with no cellphone coverage, and that stretches of the road are steep, narrow and rocky. Visitors should take plenty of water, have at least one spare tire (preferably a full-size one) and be able to change or repair a flat tire on a dirt road.

Information: Lake Havasu Field Office, 928-505-1200 or www.blm.gov/arizona

GHOST TOWN DIRECTORY

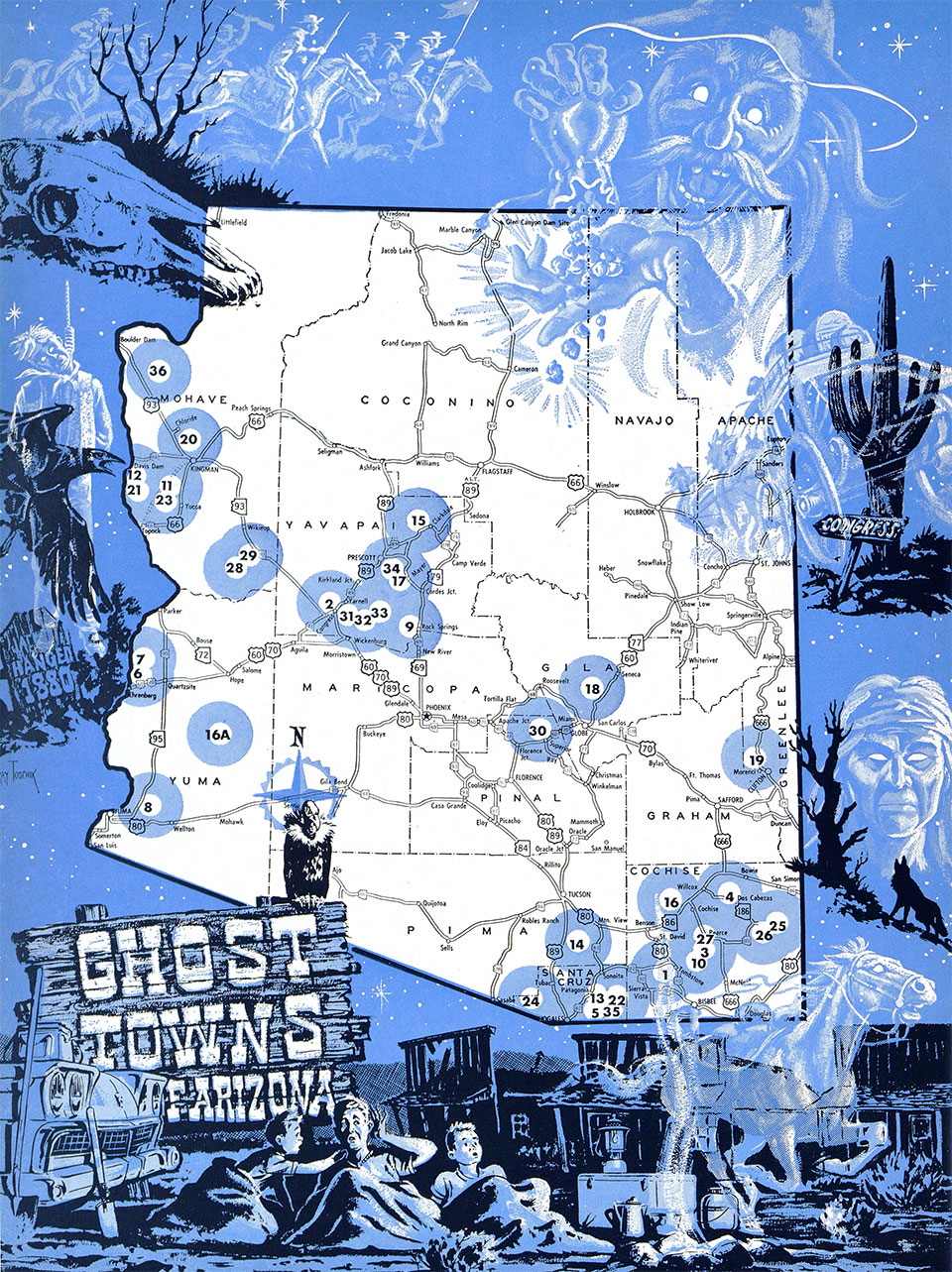

Originally published in the August 1960 issue of Arizona Highways.

Editor’s Note: Ghost towns have been a popular topic for us for many years. One of the most extensive pieces was published in August 1960. The story that month was written by Nell Murbarger, who, according to our editors, was widely known as “the Roving Reporter of the Desert.” Among the 18 pages was this wonderful map by Larry Toschik, who was a longtime illustrator for us.

| 1. CHARLESTON | 2. CONGRESS | 3. COURTLAND | 4. DOS CABEZAS | |||

| 5. DUQUESNE | 6. EHRENBERG | 7. LA PAZ | 8. GILA CITY | |||

| 9. GILLETT | 10. GLEESON | 11. GOLDROAD | 12. HARDYVILLE | |||

| 13. HARSHAW | 14. HELVETIA | 15. JEROME | 16. JOHNSON; 16A. KOFA | |||

| 17. McCABE | 18. McMILLENVILLE | 19. METCALF | 20. MINERAL PARK | |||

| 21. MOHAVE CITY | 22. MOWRY | 23. OATMAN | 24. ORO BLANCO | |||

| 25. PARADISE | 26. GALEYVILLE | 27. PEARCE | 28. SIGNAL | |||

| 29. GREENWOOD | 30. SILVER KING | 31. STANTON | 32. WEAVER | |||

| 33. OCTAVE | 34. WALKER | 35. WASHINGTON | 36. WHITE HILLS |