At 6 p.m. on a late-June evening, it’s 102 degrees at Stella Tucker’s campsite at Saguaro National Park. A graniteware pot bubbles over a fire, the fragrance of burning mesquite mingling with the sweet smell of saguaro-fruit juice cooking down into syrup.

Tucker’s round, caramel-colored face shines with perspiration, strands of steel-gray hair stuck to her forehead under a wide-brimmed straw hat. She wears jeans, Crocs and a turtle necklace representing the daughter she lost to kidney disease.

“We used to call her ‘Turtle,’ because she was never in a hurry to do anything,” Tucker explains with a chuckle.

June is the hottest month in the Sonoran Desert, with Tucson temperatures soaring as high as 115. It’s also the month the saguaro fruit begins to ripen. So every year, as the mercury rises, Tucker comes to this campsite at the foot of the Tucson Mountains to harvest saguaro fruit, as Tohono O’odham women have done for millennia.

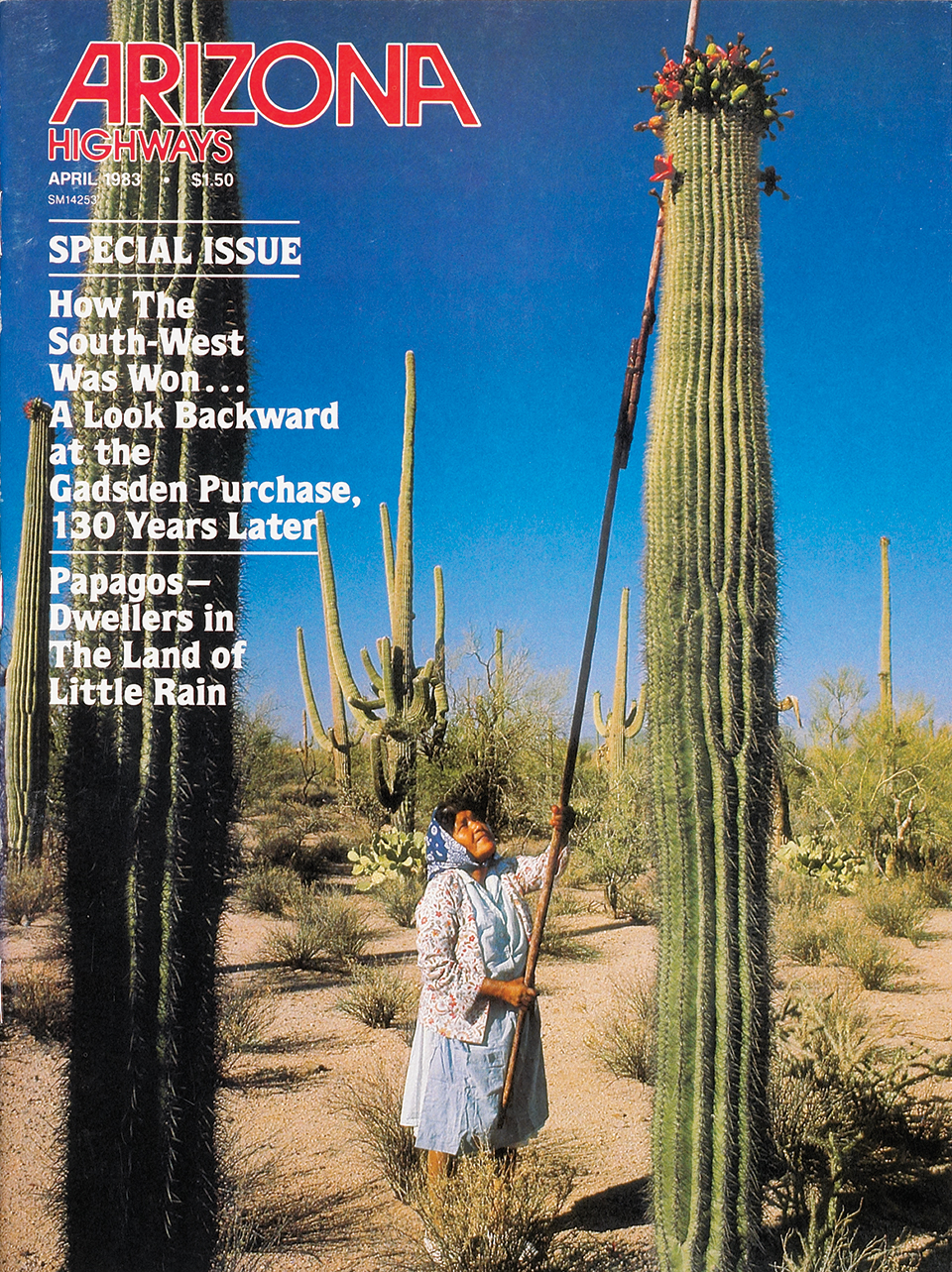

Called Papagos by the Spanish, the Tohono O’odhams have made the Sonoran Desert their home for centuries, sustaining themselves largely on wild foods and flood-based farming. Historically, they relied on the saguaro harvest and wine feast to usher in the monsoon storms that made both possible; the ceremonies are so central to the tribe’s culture that they mark the Tohono O’odham new year. With few tribe members still involved in traditional food practices, Tucker’s harvest at Saguaro National Park has become an increasingly important resource for Native and non-Native people alike.

“There used to be a lot of families here,” Tucker says, pointing to various spots around the campsite. “There was a family there, two families camped out over there, a third one on that side and then a family right there.”

The elders died off, she says. And the children never took over.

Traditionally, Tohono O’odham families returned to the same groves every year. Tucker’s grandmother, Juanita Ahil, harvested this area long before the formation of Saguaro National Park. After the park’s creation, Ahil welcomed visitors, giving demonstrations and sharing her knowledge. Now, Tucker and her daughter Tanisha have picked up the mantle.

And there’s a lot of interest. Non-Native students often come via workshops scheduled by the national park. Native people have come from Alaska, the Dakotas and Oklahoma.

“They came from all over,” Tucker says.

Tonight, ethnobotanist Carrie Cannon will camp overnight, hoping Tucker’s process can inform her work with Northwestern Arizona’s Hualapai Tribe, whose southernmost band once harvested saguaro fruit near Wikieup.

Tucker admits the workshops can be exhausting. “But I do enjoy them,” she says.

At 7 A.M. the next day, the sun feels oppressive as cars pull in for a workshop organized through a grant-funded project called Standing with Saguaros. The 15 available slots filled up within a few hours.

At 69, Tucker walks with a cane and is no longer up to the rigors of picking. So she sits under the shade of a ramada while Tanisha demonstrates. Using a picking pole, made of saguaro ribs and a crosspiece of greasewood, Tanisha pushes and pulls the fruit to the ground. Then she demonstrates how to use the hard, sharp base of the spent blossom to cut through the fruit’s thick skin before scooping out the seedy red pulp with her thumb. She tells participants to leave the pods face up on the ground next to the saguaro.

“It’s just to say thank you, and also to bring rain for the next harvest,” she says. “The first fruit you pick, do a little bit of a blessing. You can do a little heart or cross, on your head and your heart.”

With that, Tucker sends pickers into the surrounding desert in groups of three, each with a picking pole and a 5-gallon bucket.

In her book Papago Woman, anthropologist Ruth Underhill documented Tohono O’odham rain ceremonies as they were practiced in the 1930s. She accompanied a family to its traditional campground, where the women harvested saguaro fruit until “the little rains” came, then carried the boiled juice back to their villages.

At a gathering at the council house of a central village, the syrup was mixed with water and left for four days to ferment. “For the last two nights,” Underhill wrote, “the whole village would dance, ‘singing down the rain.’ ”

At dawn on the third day, the medicine man told the people to go home and prepare a feast, “for in four days the rain will come.”

“I asked later … whether [the prophecy] was always fulfilled,” Underhill wrote. “ ‘Oh yes, yes,’ was the usual answer. … Maybe the rain come soon and he says, ‘Yes, but I counted from when the wagons arrived,’ or it come late and then, ‘I meant four days after the wine had fermented.’ ”

At the wine feast, a Tohono O’odham woman told Underhill, the people must make themselves “beautifully drunk, for that is how our words have it. People must all make themselves drunk like plants in the rain and they must sing for happiness.”

The wine feast involved an elaborate ceremony, with the important men of neighboring villages kneeling behind their leaders, and young men with horses in the final row.

“The Smokekeeper of each town came ready with his acceptance speech,” Underhill wrote. “This … had been carried in memory through generations. They must be recited word for word or the rain would not come.”

Although it’s believed the Tohono O’odhams have harvested the cactus fruit in the park’s Tucson Mountain District for as long as they’ve lived in the Sonoran Desert, the 1961 presidential proclamation adding the district to what then was Saguaro National Monument didn’t include a provision for traditional harvesting. So park officials were surprised when more than 200 Native people, many of them children, showed up to pick.

In response to letters alerting him to the oversight, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall successfully pressed to amend regulations and allow the Tohono O’odhams to continue to harvest there. It took years to iron out the issues, with myriad mistakes and misunderstandings contributing to the confusion, but now the National Park Service grants special use permits for the campground Tucker returns to each year.

Tucker attended her first saguaro harvest with her great-grandparents, when she was too young to pick.

“We had our own camp in Topawa,” a small village south of Sells on the Tohono O’odham Nation, she says. “We’d load up and go by wagon.”

Eventually, she moved to Tucson, got a job and got married. By then, Ahil was camping near the road not far from the current campsite in the national park. When the campsite was designated, Ahil built a ramada there and returned every year for the harvest. As Ahil got older, Tucker came out to help, eventually taking over Ahil’s campsite after Ahil couldn’t continue. Tucker and Tanisha are the only tribal members who continue to camp there year after year.

A rain singer used to come to camp to sing at the end of the harvest. Since he died, there has been no one to sing the songs. Likewise, there are no more wine feasts in Topawa, Tucker says, though she sometimes donates syrup to other villages. It’s estimated that only two or three still hold wine feasts, which are generally closed to those outside the tribe. But Tohono O’odham Community College and Tohono O’odham Community Action keep the harvest tradition alive.

As workshop participants straggle back to camp with stained fingers, lugging buckets of fruit, they pepper Tucker with questions. Her face lights up as she responds in between instructions to add water and break up the fruit with their hands.

Because it’s summer, she doesn’t share Tohono O’odham stories about the saguaro, the harvest and the wine feast. The stories are told only in winter, when snakes are hibernating. Otherwise, the snakes come around, Tucker says.

Anthropologists have recorded several variations. In one, a baby neglected by his mother sinks into the ground, coming up on a mountain slope as a giant cactus. A crow finds him, but the boy refuses to go home. Instead, he slowly turns himself into a saguaro, teaching the people rain songs and how to make wine.

With the fruit on the fire, Tucker opens a Mason jar filled with syrup, offering a taste of the sweet, smoky liquid with crackers. She enjoys the syrup on bread or as a treat on vanilla ice cream.

“We don’t have to add sugar to this,” she tells them. “It’s all natural. Our family grew up around the desert. We ate a lot of stuff that grows in the desert, and people didn’t have diabetes.”

Today, the Tohono O’odham Nation’s rate of adult-onset diabetes is among the highest in the world.

The cooking fruit foams, carrying any bits of grass and dirt to the top to get skimmed off. Tucker supervises as participants strain the juice twice — first through a screen, then through cheesecloth, leaving a bright red liquid the color of pomegranate juice. Over the next few hours, it will darken as it cooks, Tucker explains, until it looks more like molasses.

The workshop organizer thanks Tucker and her daughter. On the count of three, Tucker leads participants in a single clap of gratitude, releasing it to the sky for the good of the saguaro, the harvest and the coming rain.

“Maybe I’ll see you guys again next year,” she says, smiling. “I’ll be here.”