EDITOR'S NOTE: The following letter from Editor Robert Stieve appears in the upcoming December 2018 issue of Arizona Highways.

I met Alison on a Saturday morning. At a parade. We were introduced by a mutual friend, one of the few hippies in Old Town Scottsdale. Like most parades, Parada del Sol is loud. It’s hardly a place to hatch a plan, but that’s where this began. This issue. This collaboration. This attempt to rescue valuable artifacts.

Despite the commotion, Alison pulled me aside and started talking — 2,600-pound Percherons, hell-bent tuba players and varsity cheerleaders are no match for Alison Goldwater Ross. She needed help.

“I’m trying to preserve my grandfather’s archive,” she said. “There are thousands of negatives and transparencies. And they’re disintegrating. Film deteriorates. Did you know that? If we don’t do something, all of that history will be lost.”

She spoke with a sense of urgency. Like Paul Revere that night in Boston. I don’t think she ever came right out and asked for help, but she didn’t have to. I’d been looking for something like this for a while. Something that might transcend the pages of the magazine. When she finally took a breath, I shared my vision. And then we started brainstorming — right there on the corner of Main Street and Brown Avenue. Two years later, the firstborn of that collaboration has arrived.

For more than 80 years, we’ve presented our December issue as an exclamation point on the calendar year. “A Celebration of the Season.” “A Postcard to the World.” Every year we try to make it something special, and 2018 is no exception. This time around, we’re featuring the photography of Barry Goldwater. Although he’s best known nationally as a public servant, a man who dedicated his life to the people of Arizona, his passion for photography was as powerful as his love of politics.

“Barry set out to visit and photograph remote parts of the state,” Matt Jaffe writes in Barry Goldwater, “bringing together an artist’s eye and an anthropologist’s commitment to record his homeland’s ancient cultures and timeless, yet fragile landscapes.”

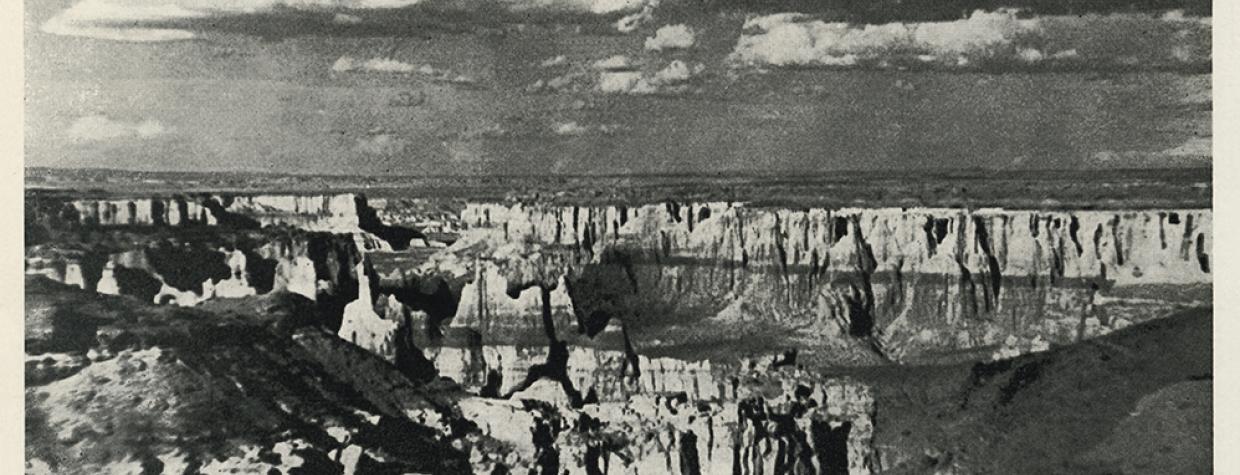

“My photographs have been taken primarily to record what Arizona looked like during my life,” Barry said. “The first photograph I sold to Arizona Highways was in 1939. [Editor Raymond Carlson] and I were driving along one day by Coal Mine Canyon up near Tuba City. Ray said, ’You wouldn’t have a picture of that, would you?’ I said, ’Yeah, I’ve got a good one.’”

The image ran on page 16 of our August 1939 issue. It was just the beginning. Many more have followed, including a portrait from June 1940 that Barry titled The Navajo. “That’s one of my better pictures,” he said. “It was taken back in 1938 at an Indian fair near Window Rock. His name is Charlie Potato, and I guess I must have printed maybe 5,000 of those.”

The Navajo is one of our favorites, too, which is why Barb used it as the opening shot in this month’s portfolio. The runner-up for that spot was a photograph that’s sometimes referred to as The Shepherdess. It first ran on the cover of our December 1946 issue. You might remember it. Arguably, it’s the most famous photograph we’ve ever published.

“It was a cold, raw winter day deep on the Navajo Reservation when Barry Goldwater took the picture we use on our cover,” Raymond Carlson wrote in his column, 72 years ago this month. “The snow clouds were low over Navajo Mountain and the little Navajo girls, watching their sheep, were wrapped in their blankets against the wind. The whole scene is real and simple.”

Turns out, that issue — with Barry’s now-legendary image on the front cover — marked the first time in history that a nationally circulated consumer magazine was published in all color, from cover to cover. In the annals of magazine publishing, that’s significant, but to Barry, it was something more.

“The great thing about photography,” he wrote, “is that through it, I was able to enjoy my state as it was growing up, and capture some of it on film so other people could have a chance to see it as I knew it. To photograph and record Arizona and its people, particularly its early settlers, was a project to which I could willingly devote my life, so that I could leave behind an indexed library of negatives and prints.”

When you do the math, there are more than 15,000 slides and transparencies in his archive, along with 25 miles of motion picture film. As he‘d requested, many of his images are housed at the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, the Hayden Library at Arizona State University and the Heard Museum in Phoenix. The rest are with the Barry & Peggy Goldwater Foundation, the nonprofit formed by Alison Goldwater to preserve her grandfather’s legacy.

Unfortunately, all of his images are in need of preservation — even under the best of circumstances, film deteriorates over time. What’s worse, as the film slowly disintegrates, so do important pieces of Arizona history. Priceless artifacts.

“What I’m setting out to do with the foundation is to fulfill his wishes,” Alison says. “His wishes were to document Arizona and show the beauty of the landscape and the people.”

The task of doing that — through digitization and optical restoration — will be costly and time-consuming, but the work has already begun, and you’ll see some of the results in our portfolio. All 46 photographs in there have been restored.

The Navajo, The Shepherdess, Big Country ... some of the images have been published in this magazine over the past eight decades. Others have never been seen before. That’s the exciting part. For us, getting access to the family archive was like being let loose in Copenhagen’s Conditori La Glace at Christmastime. There were so many photos to choose from. Too many. Ultimately, we had to expand the issue to 100 pages. And even then, narrowing it down was a challenge. So was writing the captions.

Although Barry created an elaborate filing system, indexed by subject, he could be stingy with details. And sometimes, he’d give multiple names to the same image. Where the information was thin or confusing or nonexistent, we relied on commentary from other photographers, including Ansel Adams, who, like our subject, was a longtime contributor to Arizona Highways.

“Senator Goldwater’s deep involvement in the affairs of the world and at the summit of political activity have undoubtedly limited the time and effort he could expend on his photography,” Mr. Adams wrote. “The important thing is that he made photographs of historical and interpretive significance, and for this we should be truly grateful. We sometimes forget that Art, in any form, is a communication. Barry Goldwater has communicated his vision of the Southwest, and he deserves high accolades for his desire to tell us what he feels and believes about his beloved land.”

We also reached out to some of our current contributors. The names are names you’ll recognize: David Muench, Jack Dykinga, Paul Markow, Paul Gill, Joel Grimes, J. Peter Mortimer. In addition to being a talented photographer, Pete was our photo editor in the early 1980s. In that role, he often visited Barry at his home in Paradise Valley.

“The first time I met Barry Goldwater,” Pete says, “was when Editor Don Dedera asked me to go to Barry’s house to get an envelope of photographs that were going to be used in the magazine. As I drove up the driveway, I noticed that the abandoned Secret Service guard shack was still there — a relic from Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign. Near the driveway, there was a man in dark shorts and a T-shirt slapping a tar-like substance onto an old, ailing saguaro. As I got closer, I realized that it was Senator Goldwater. I rolled down the car window and he said, ‘You’ve come for the pictures?’ I told him yes, and then I asked what was wrong with the cactus. He looked over at the saguaro and said, ‘Oh, I don’t think these damn things like us very much!’ Then he added, ‘Go up to the house and get some iced tea; I’ll be there in a few minutes.’ Over the years, I was lucky enough to make a number of trips to his house to get photographs. I always looked forward to hearing him talk about the specific images that he was sending back to the magazine.”

In all, we’ve published hundreds of Barry’s photographs, the best of which will be on display from January 6 through June 23 at Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West. The exhibition, Photographs by Barry M. Goldwater: The Arizona Highways Collection, is another one of the ideas that Alison and I talked about during the parade.

It was an idea that took off, and now, so many months later, Arizona Highways is proud to be partnering with the Barry & Peggy Goldwater Foundation on this important show, a show that wouldn’t be possible without the generous support of Salt River Project. SRP has a long history of supporting arts and culture in Arizona, and this exhibition is another one of the many beneficiaries. On behalf of the Goldwater family and everyone at this magazine, thank you, SRP. We look forward to what’s ahead, including more exhibitions, a coffee table book and a line of related products, all of which will benefit the foundation in its ongoing effort to preserve those 15,000 images.

Stay tuned for details on all of the above. Meantime, whether you celebrate Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa or just a few days off in December, happy holidays, and thank you for spending another year with Arizona Highways.