THE BARD OF ROCK HISTORY

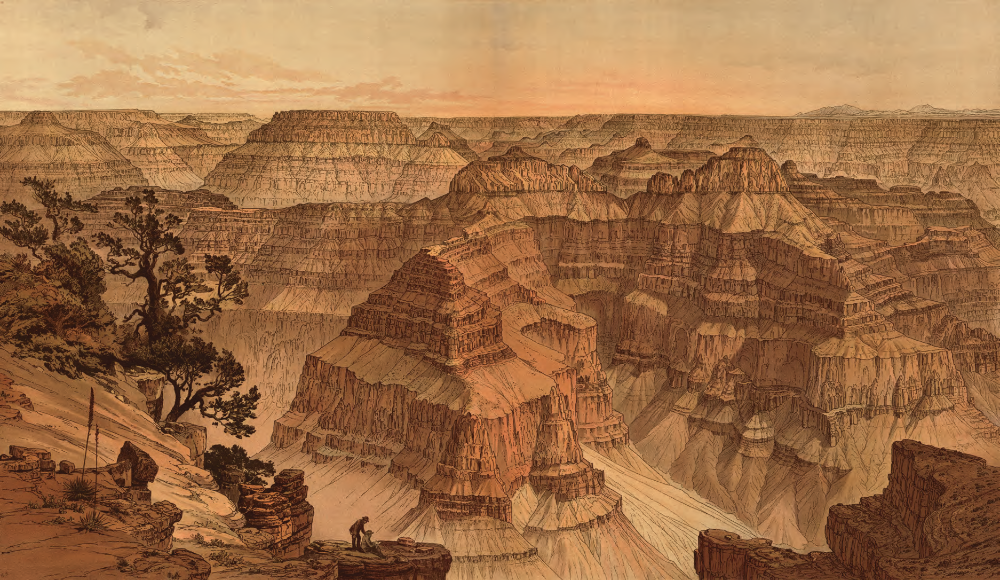

I MET CLARENCE DUTTON WHILE unpacking books. There he was, in an original 1882 edition of the Atlas to Accompany the Monograph on the Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District. Or, rather, all that he saw, identified, named, wrote about, poeticized about was there. The atlas, 18 by 20.3 inches, slim, elegant, hardbound in brown cloth with a gilt title on the cover, is a work of art. The monograph accompanying it, an early publication of the newly designated U.S. Geological Survey, could be called a work of poetry. The atlas contains remarkable drawings by William Henry Holmes and Thomas Moran, along with 12 geological maps that create a 270-degree panorama of the Grand Canyon. In one illustration, Holmes included himself seated on a rock, drawing, while Dutton, at his back, leans over to see the work, his hand apparently resting on Holmes' shoulder. The figures are tiny in the vastness of the space, the moment hugely personal. I previously had known nothing about Dutton, but the atlas made me curious. Online, I found a 2018 article about him, written for the National Geographic Society's 130th anniversary celebration (Dutton was among the society's 33 founders). Referring to his geological work in Utah's High Plateaus, which preceded and somewhat overlapped his work at the Canyon, he was quoted as writing, “There is an eloquence in (these) forms which stirs the imagination with a singular power and kindles in the mind a glowing response.” I had never encountered geology that sounded like that. Eager to read Dutton's work, I bought everything I could find.

CLARENCE EDWARD DUTTON - soldier, geologist, poet, raconteur, lover of good cigars, good drink and good society - had the heart, the mind, the vision, the vocabulary and the literary background to describe not only the geology of the Grand Canyon, but also the feelings evoked in him in its presence. In Dutton's writing, geology and literary expression combine like perfect bedfellows. Wallace Stegner, who wrote his Ph.D. thesis on Dutton, called him “the most literary of all geologists.” I call him awesome.

In a 1936 published version of his thesis (Clarence Edward Dutton: An Appraisal), Stegner wrote that “a monograph written as Dutton's are written would never be accepted for publication by the Geological Survey today.” He continues, “Dutton's works are probably the finest things from the standpoint of literary merit in the whole history of American geology.” Dutton acknowledged his departure from “the severe ascetic style ... conventional in scientific monographs” in the preface to his Tertiary History. He opined that poetic language about the Grand Canyon was necessary to “exalt the mind sufficiently to comprehend the sublimity of the subjects.” “Sublime” is the operative word, a word forever incorporated into the fabric of the Canyon - not only because the Canyon is sublime, but also because Dutton named a vital North Rim overlook Point Sublime.

What must it have been like to be present in this landscape when few people - beyond those who had lived there for thousands of years even knew it existed?

Dutton began three seasons at the Grand Canyon nine years after his boss, John Wesley Powell, first ran the river. (Both men were preceded by Joseph Ives, who traveled upriver in 1857 and '58, but Ives' dismissal of the Canyon afterward as “altogether valueless” renders him, for me, beside the point.) My encounter with Dutton is recent, by chance and powerful. His language describes my feelings. Although I've been hiking at the Canyon for many years, I also spent much of my life ignoring it. Because it possessed no soaring mountains for me to climb, it seemed to me a place for sightseers, a destination for families on summer vacation, a cliché. Then, one day, driving back to Montana from the Navajo Nation, where I'd gone to do a story, I passed close to the South Rim. How could I not stop?

And there it was. That instant. That edge. That revelation that on the whole of Earth, in the whole of life, there would never be a moment more transcendent. Dutton nailed it when he described the moment that makes “the heart ache and the throat tighten.” Dutton was adept at presenting emotion, but his descriptions also are full of architectural references. For him, the forms and shapes of the Canyon were architecture. The names he gave many of them - Brahma Temple, Deva Temple, Hindu Amphitheater, Shiva Temple, Vulcan's Throne, Zoroaster Temple - certainly reflect a sense of the architectural, not to mention the 19th century's fascination with Eastern religion. “To the conception of its vast proportions must be added some notion of its intricate plan, the nobility of its architecture, its colossal buttes, its wealth of ornamentation, the splendor of its colors, and its wonderful atmosphere,” he wrote. “All of these attributes combine with infinite complexity to produce a whole which at first bewilders and at length overpowers.” These last words echo that sense I had on first standing at the Canyon's edge. Nothing in my experience prepared me for it. No other place looks like it, stirs like it. The Canyon is not simply one more remarkable act of nature. It is some incomprehensible, staggering, overwhelming event confronting us with an eternity we never imagined. It is a geology requiring a poet.

DUTTON'S ROUTE TO GEOLOGY seems more or less one of chance. Although as a child he built himself a laboratory to study rocks and minerals, at Yale, which he entered at age 15, he focused on chemistry, physics, gymnastics, crew and chess. (That is, after he left Yale Divinity School, which happened not long after he entered it.) Even then, chemistry and physics took second place to sport. But he was a voracious reader, winning the Yale Literary Medal his senior year (he was 19) with an essay on Charles Kingsley, a 19th century Anglican priest, amateur naturalist, sportsman, novelist and essayist. A friend who is an emeritus professor of English with a passion for 19th century literature tells me Kingsley's works are not included in any of his anthologies, which says something about Kingsley's current standing in literature. But Kingsley excelled in his descriptions of place, a skill that would have resonated with the young Dutton. He also was sympathetic to the new idea of evolution, and in this, he shared Dutton's sense of a logic in nature.

Born in 1841, Dutton, a Victorian growing up in an age just removed from the Romantic era's literary and artistic celebration of nature, was influenced by the Romantic writers in his approach to nature writing. A layer of Jurassic rock could be not just a layer of Jurassic rock, but a story of form and color and light - the Earth's stories as revealing as those of any great writer. Dutton had time for two years of graduate studies before the Civil War broke out. Joining the Army's 21st Connecticut Infantry Regiment as a first lieutenant in 1862, he was wounded at the Battle of Fredericksburg but recovered to engage in later battles, then transferred to the Ordnance Corps in 1864. According to the article celebrating the National Geographic Society anniversary, Dutton preferred being on “the sending rather than the receiving end of shells.” The choice may have had more to do with his quality of mind: a mind capable of putting everything in order. Still, ordnance, regardless of the intricate managing it requires, seems to me too ordinary for Dutton's brilliance. Adventuresome, fit and curious, he engaged in scientific study wherever he was posted. Sent to Washington, D.C., he met Powell, who persuaded him to become a geologist, then asked himto lead the Powell Survey. Powell also arranged for Dutton to be on seasonal release from the Ordnance Corps for the next 15 years. Dutton's job was to map the topography and describe the geology of the vast Colorado Plateau, the last area of the country to be systematically explored and surveyed. He began his explorations on Utah's High Plateaus region, which includes the areas of Bryce Canyon and Zion Canyon. His early writing seems less freely poetic, although there is a noticeable change at the Aquarius Plateau. Maybe Dutton was simply happy to see trees. In any case, the poet was unleashed. “The Aquarius should be described in blank verse and illustrated upon,” he wrote. “The explorer whosits upon the brink of its parapet ... forgets he is a geologist and feels himself a poet." By the time Dutton began his survey of the Grand Canyon, the poet was as present as the geologist. Writing about Jurassic cliffs "devoid of ornament as a fortress," he still found them "full of life, variety and expression." Marveling at "domes and half-domes of bald white rock which look a calm defiance of human intrusion," he also noted that "occasionally, the austerity of these forms is exchanged for those of the opposite extreme, as if Nature were tired of ... all this solemn dignity, and the proverbial step from the sublime to the ridiculous is actually taken. How alive this nature is for him! How extraordinary that he could spend intimate time with it before the rest of us rushed in.

The work in plateau country produced a trilogy of books: Report on the Geology of the High Plateaus of Utah, The Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District, and Mount Taylor and the Zuni Plateau. This last focuses on the eroded remnants of volcanoes, an interest that occupies much of Dutton's exploration in Report on the Geology of the High Plateaus of Utah. (Dutton, appointed by Powell, served as head of the Department of Volcanic Geology at the Geological Survey, traveling to Hawaii in 1882 to study volcanoes.) This master of words is credited with coining at least two: “caldera,” as a term for a volcano's crater, and “isostasy,” meaning an equilibrium of the Earth's crust, a condition in which the forces tending to elevate balance those tending to depress.

Taylor and the Zuni Plateau. This last focuses on the eroded remnants of volcanoes, an interest that occupies much of Dutton's exploration in Report on the Geology of the High Plateaus of Utah. (Dutton, appointed by Powell, served as head of the Department of Volcanic Geology at the Geological Survey, traveling to Hawaii in 1882 to study volcanoes.) This master of words is credited with coining at least two: “caldera,” as a term for a volcano's crater, and “isostasy,” meaning an equilibrium of the Earth's crust, a condition in which the forces tending to elevate balance those tending to depress.

An 1886 earthquake in Charleston, South Carolina, turned Dutton's focus to seismology. (So, maybe the Ordnance Corps, with its intimacy with explosive events, was the right place for him.) His last book, Earthquakes in the Light of the New Seismology, was published in 1904, three years after he retired from the Army. Two years later, intrigued by the discovery of radioactivity, he published a paper exploring the possibility of radioactive heat as a basic cause of volcanic activity.

“Let us not underrate the versatility and resources of Nature, nor question her good taste,” Dutton wrote in his Tertiary History. Now that I know him better, I would say that about Clarence Dutton, too. AH

Already a member? Login ».